With the tools of modern neuroscience, data accumulates quickly. Recording devices listen in on the electrical conversations between neurons, picking up the voices of hundreds of cells at a time. Microscopes zoom in to illuminate the brain’s circuitry, capturing thousands of images of cells’ elaborately branched paths. Functional MRIs detect changes in blood flow to map activity within a person’s brain, generating a complete picture by compiling hundreds of scans.

“When I entered neuroscience about 20 years ago, data were extremely precious, and ideas, as the expression went, were cheap. That’s no longer true,” says McGovern Associate Investigator Ila Fiete. “We have an embarrassment of wealth in the data but lack sufficient conceptual and mathematical scaffolds to understand it.”

Fiete will lead the McGovern Institute’s new K. Lisa Yang Integrative Computational Neuroscience (ICoN) Center, whose scientists will create mathematical models and other computational tools to confront the current deluge of data and advance our understanding of the brain and mental health. The center, funded by a $24 million donation from philanthropist Lisa Yang, will take a uniquely collaborative approach to computational neuroscience, integrating data from MIT labs to explain brain function at every level, from the molecular to the behavioral.

“Driven by technologies that generate massive amounts of data, we are entering a new era of translational neuroscience research,” says Yang, whose philanthropic investment in MIT research now exceeds $130 million. “I am confident that the multidisciplinary expertise convened by this center will revolutionize how we synthesize this data and ultimately understand the brain in health and disease.”

Data integration

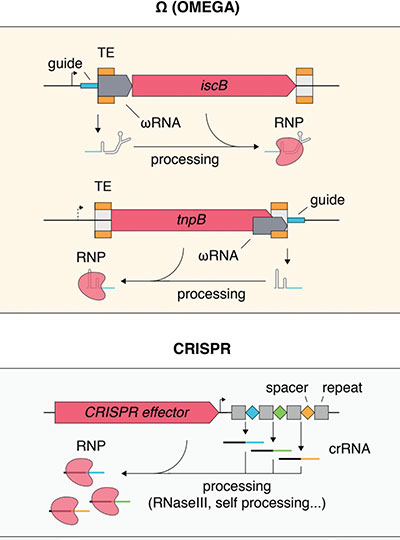

Fiete says computation is particularly crucial to neuroscience because the brain is so staggeringly complex. Its billions of neurons, which are themselves complicated and diverse, interact with one other through trillions of connections.

“Conceptually, it’s clear that all these interactions are going to lead to pretty complex things. And these are not going to be things that we can explain in stories that we tell,” Fiete says. “We really will need mathematical models. They will allow us to ask about what changes when we perturb one or several components — greatly accelerating the rate of discovery relative to doing those experiments in real brains.”

By representing the interactions between the components of a neural circuit, a model gives researchers the power to explore those interactions, manipulate them, and predict the circuit’s behavior under different conditions.

“You can observe these neurons in the same way that you would observe real neurons. But you can do even more, because you have access to all the neurons and you have access to all the connections and everything in the network,” explains computational neuroscientist and McGovern Associate Investigator Guangyu Robert Yang (no relation to Lisa Yang), who joined MIT as a junior faculty member in July 2021.

Many neuroscience models represent specific functions or parts of the brain. But with advances in computation and machine learning, along with the widespread availability of experimental data with which to test and refine models, “there’s no reason that we should be limited to that,” he says.

Robert Yang’s team at the McGovern Institute is working to develop models that integrate multiple brain areas and functions. “The brain is not just about vision, just about cognition, just about motor control,” he says. “It’s about all of these things. And all these areas, they talk to one another.” Likewise, he notes, it’s impossible to separate the molecules in the brain from their effects on behavior – although those aspects of neuroscience have traditionally been studied independently, by researchers with vastly different expertise.

The ICoN Center will eliminate the divides, bringing together neuroscientists and software engineers to deal with all types of data about the brain. To foster interdisciplinary collaboration, every postdoctoral fellow and engineer at the center will work with multiple faculty mentors. Working in three closely interacting scientific cores, fellows will develop computational technologies for analyzing molecular data, neural circuits, and behavior, such as tools to identify pat-terns in neural recordings or automate the analysis of human behavior to aid psychiatric diagnoses. These technologies will also help researchers model neural circuits, ultimately transforming data into knowledge and understanding.

“Lisa is focused on helping the scientific community realize its goals in translational research,” says Nergis Mavalvala, dean of the School of Science and the Curtis and Kathleen Marble Professor of Astrophysics. “With her generous support, we can accelerate the pace of research by connecting the data to the delivery of tangible results.”

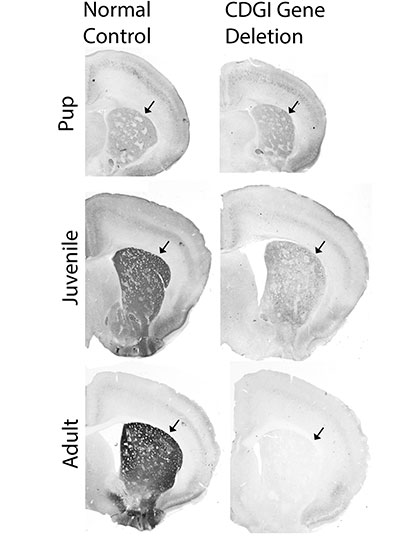

Computational modeling

In its first five years, the ICoN Center will prioritize four areas of investigation: episodic memory and exploration, including functions like navigation and spatial memory; complex or stereotypical behavior, such as the perseverative behaviors associated with autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder; cognition and attention; and sleep. The goal, Fiete says, is to model the neuronal interactions that underlie these functions so that researchers can predict what will happen when something changes — when certain neurons become more active or when a genetic mutation is introduced, for example. When paired with experimental data from MIT labs, the center’s models will help explain not just how these circuits work, but also how they are altered by genes, the environment, aging, and disease.

These focus areas encompass circuits and behaviors often affected by psychiatric disorders and neurodegeneration, and models will give researchers new opportunities to explore their origins and potential treatment strategies. “I really think that the future of treating disorders of the mind is going to run through computational modeling,” says McGovern Associate Investigator Josh McDermott.

In McDermott’s lab, researchers are modeling the brain’s auditory circuits. “If we had a perfect model of the auditory system, we would be able to understand why when somebody loses their hearing, auditory abilities degrade in the very particular ways in which they degrade,” he says. Then, he says, that model could be used to optimize hearing aids by predicting how the brain would interpret sound altered in various ways by the device.

Similar opportunities will arise as researchers model other brain systems, McDermott says, noting that computational models help researchers grapple with a dauntingly vast realm of possibilities. “There’s lots of different ways the brain can be set up, and lots of different potential treatments, but there is a limit to the number of neuroscience or behavioral experiments you can run,” he says. “Doing experiments on a computational system is cheap, so you can explore the dynamics of the system in a very thorough way.”

The ICoN Center will speed the development of the computational tools that neuroscientists need, both for basic understanding of the brain and clinical advances. But Fiete hopes for a culture shift within neuroscience, as well. “There are a lot of brilliant students and postdocs who have skills that are mathematics and computational and modeling based,” she says. “I think once they know that there are these possibilities to collaborate to solve problems related to psychiatric disorders and how we think, they will see that this is an exciting place to apply their skills, and we can bring them in.”