This story is adapted from a News@Northeastern post.

We all do it. One second you’re fully focused on the task in front of you, a conversation with a friend, or a professor’s lecture, and the next second your mind is wandering to your dinner plans.

But how does that happen?

“We spend so much of our daily lives engaged in things that are completely unrelated to what’s in front of us,” says Aaron Kucyi, neuroscientist and principal research scientist in the department of psychology at Northeastern. “And we know very little about how it works in the brain.”

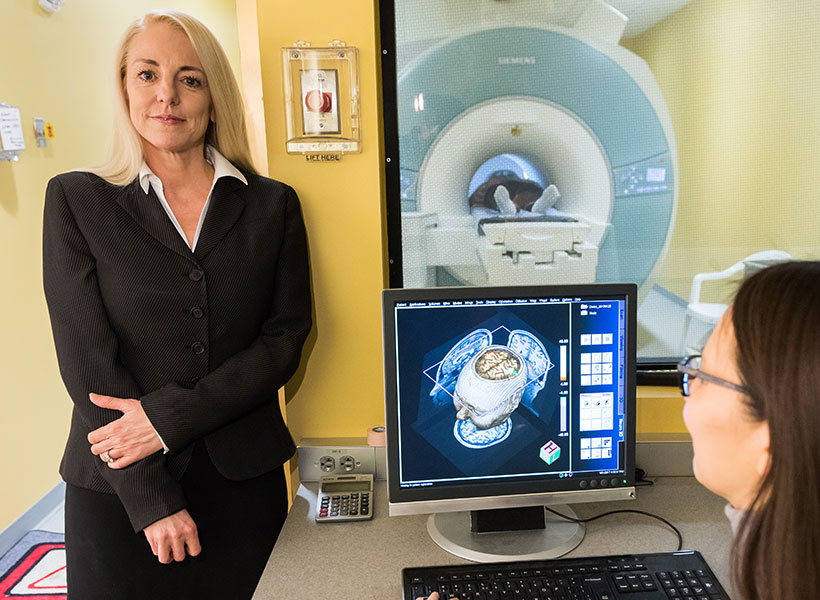

So Kucyi and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston University, and the McGovern Institute at MIT started scanning people’s brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to get an inside look. Their results, published Friday in the journal Nature Communications, add complexity to our understanding of the wandering mind.

It turns out that spacing out might not deserve the bad reputation that it receives. Many more parts of the brain seem to be engaged in mind-wandering than previously thought, supporting the idea that it’s actually a quite dynamic and fundamental function of our psychology.

“Many of those things that we do when we’re spacing out are very adaptive and important to our lives,” says Kucyi, the paper’s first author. We might be drafting an email in our heads while in the shower, or trying to remember the host’s spouse’s name while getting dressed for a party. Moments when our minds wander can allow space for creativity and planning for the future, he says, so it makes sense that many parts of the brain would be engaged in that kind of thinking.

But mind wandering may also be detrimental, especially for those suffering from mental illness, explains the study’s senior author, Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli. “For many of us, mind wandering may be a healthy, positive and constructive experience, like reminiscing about the past, planning for the future, or engaging in creative thinking,” says Whitfield-Gabrieli, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and a McGovern Institute research affiliate. “But for those suffering from mental illness such as depression, anxiety or psychosis, reminiscing about the past may transform into ruminating about the past, planning for the future may become obsessively worrying about the future and creative thinking may evolve into delusional thinking.”

Identifying the brain circuits associated with mind wandering, she says, may reveal new targets and better treatment options for people suffering from these disorders.

Inside the wandering mind

To study wandering minds, the researchers first had to set up a situation in which people were likely to lose focus. They recruited test subjects at the McGovern Institute’s Martinos Imaging Center to complete a simple, repetitive, and rather boring task. With an fMRI scanner mapping their brain activity, participants were instructed to press a button whenever an image of a city scene appeared on a screen in front of them and withhold a response when a mountain image appeared.

Throughout the experiment, the subjects were asked whether they were focused on the task at hand. If a subject said their mind was wandering, the researchers took a close look at their brain scans from right before they reported loss of focus. The data was then fed into a machine-learning algorithm to identify patterns in the neurological connections involved in mind-wandering (called “stimulus-independent, task-unrelated thought” by the scientists).

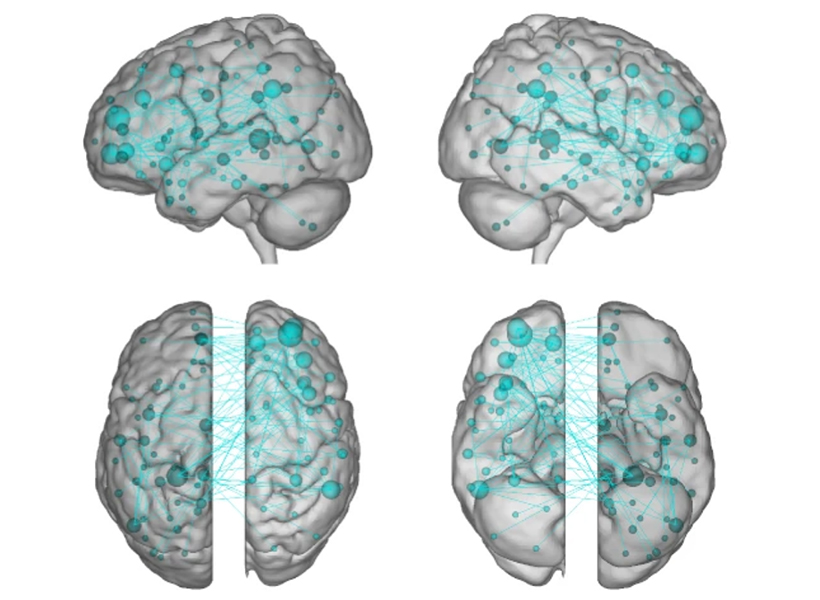

Scientists previously identified a specialized system in the brain considered to be responsible for mind-wandering. Called the “default mode network,” these parts of the brain activated when someone’s thoughts were drifting away from their immediate surroundings and deactivated when they were focused. The other parts of the brain, that theory went, were quiet when the mind was wandering, says Kucyi.

The “default mode network” did light up in Kucyi’s data. But parts of the brain associated with other functions also appeared to activate when his subjects reported that their minds had wandered.

For example, the “default mode network” and networks in the brain related to controlling or maintaining a train of thought also seemed to be communicating with one another, perhaps helping explain the ability to go down a rabbit hole in your mind when you’re distracted from a task. There was also a noticeable lack of communication between the “default mode network” and the systems associated with sensory input, which makes sense, as the mind is wandering away from the person’s immediate environment.

“It makes sense that virtually the whole brain is involved,” Kucyi says. “Mind-wandering is a very complex operation in the brain and involves drawing from our memory, making predictions about the future, dynamically switching between topics that we’re thinking about, fluctuations in our mood, and engaging in vivid visual imagery while ignoring immediate visual input,” just to name a few functions.

The “default mode network” still seems to be key, Kucyi says. Virtual computer analysis suggests that if you took the regions of the brain in that network out of the equation, the other brain regions would not be able to pick up the slack in mind-wandering.

Kucyi, however, didn’t just want to identify regions of the brain that lit up when someone said their mind was wandering. He also wanted to be able to use that generalized pattern of brain activity to be able to predict whether or not a subject would say that their focus had drifted away from the task in front of them.

That’s where the machine-learning analysis of the data came in. The idea, Kucyi says, is that “you could bring a new person into the scanner and not even ask them whether they were mind-wandering or not, and have a good estimate from their brain data whether they were.”

The ADHD brain

To test the patterns identified through machine learning, the researchers brought in a new set of test subjects – people diagnosed with ADHD. When the fMRI scans lit up the parts of the brain Kucyi and his colleagues had identified as engaged in mind-wandering in the first part of the study, the new test subjects reported that their thoughts had drifted from the images of cities and mountains in front of them. It worked.

Kucyi doesn’t expect fMRI scans to become a new way to diagnose ADHD, however. That wasn’t the goal. Perhaps down the road it could be used to help develop treatments, he suggests. But this study was focused on “informing the biological mechanisms behind it.”

John Gabrieli, a co-author on the study and director of the imaging center at MIT’s McGovern Institute, adds that “there is recent evidence that ADHD patients with more mind-wandering have many more everyday practical and clinical difficulties than ADHD patients with less mind-wandering. This is the first evidence about the brain basis for that important difference, and points to what neural systems ought to be the targets of intervention to help ADHD patients who struggle the most.”

For Kucyi, the study of “mind-wandering” goes beyond ADHD. And the contents of those straying thoughts may be telling, he says.

“We just asked people whether they were focused on the task or away from the task, but we have no idea what they were thinking about,” he says. “What are people thinking about? For example, are those more positive thoughts or negative thoughts?” Such answers, which he hopes to explore in future research, could help scientists better understand other pathologies such as depression and anxiety, which often involve rumination on upsetting or worrisome thoughts.

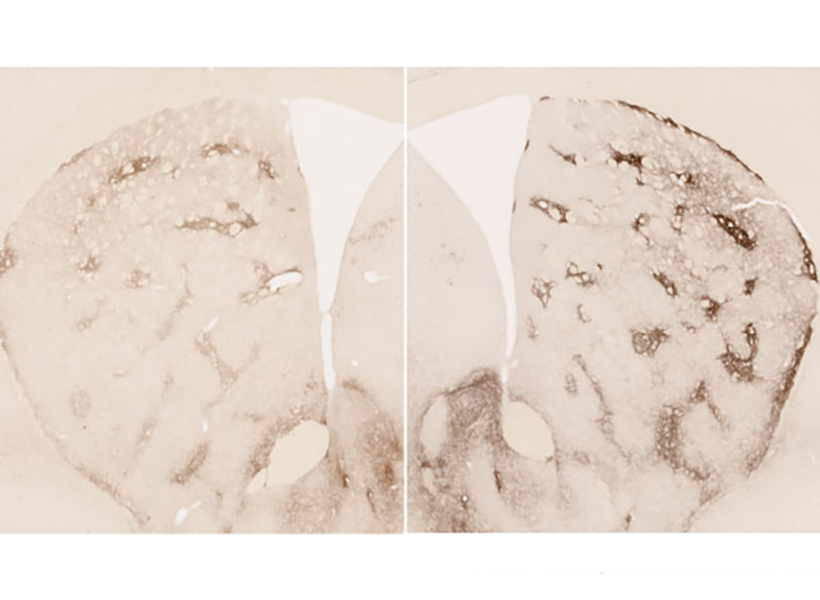

Whitfield-Gabrieli and her team are already exploring whether behavioral interventions, such as mindfulness based real-time fMRI neurofeedback, can be used to help train people suffering from mental illness to modulate their own brain networks and reduce hallucinations, ruminations, and other troubling symptoms.

“We hope that our research will have clinical implications that extend far beyond the potential for identifying treatment targets for ADHD,” she says.

View the interactive version of this story in our

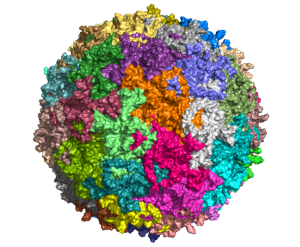

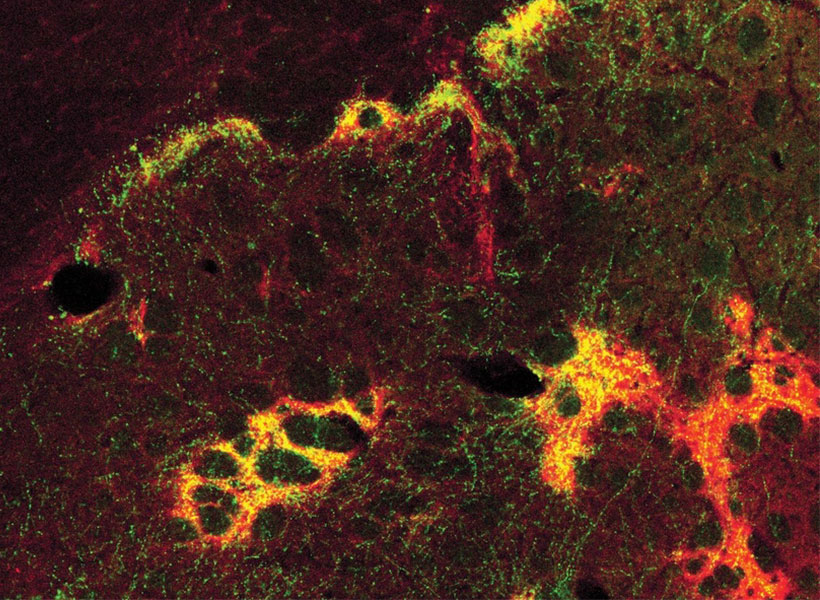

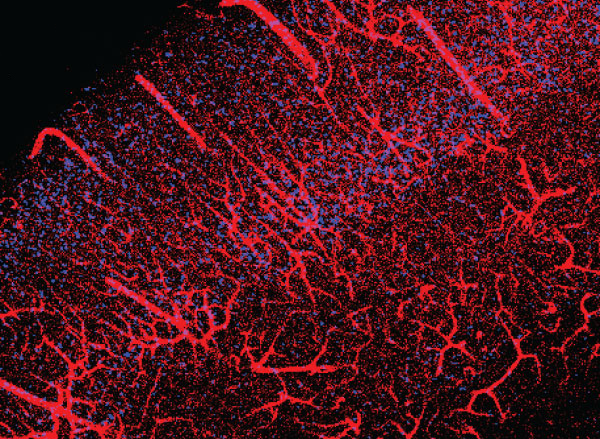

View the interactive version of this story in our  Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from.

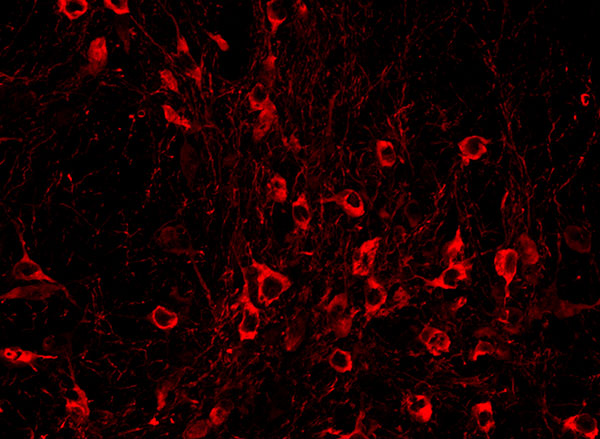

Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from. In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret.

In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret. Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.

Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.