Watch our holiday greeting on YouTube.

Animation courtesy of Jacob Pryor.

Watch our holiday greeting on YouTube.

Animation courtesy of Jacob Pryor.

Hormones and nutrients bind to receptors on cell surfaces by a lock-and-key mechanism that triggers intracellular events linked to that specific receptor. Drugs that mimic natural molecules are widely used to control these intracellular signaling mechanisms for therapy and in research.

In a new publication, a team led by McGovern Institute Associate Investigator Polina Anikeeva and Oregon Health & Science University Research Assistant Professor James Frank introduce a microfiber technology to deliver and activate a drug that can be induced to bind its receptor by exposure to light.

“A significant barrier in applying light-controllable drugs to modulate neural circuits in living animals is the lack of hardware which enables simultaneous delivery of both light and drugs to the target brain area,” says Frank, who was previously a postdoctoral associate in Anikeeva’s Bioelectronics group at MIT. “Our work offers an integrated approach for on-demand delivery of light and drugs through a single fiber.”

These devices were used to deliver a “photoswitchable” drug deep into the brain. So-called “photoswitches” are light-sensitive molecules that can be attached to drugs to switch their activity on or off with a flash of light – the use of these drugs is called photopharmacology. In the new study, photopharmacology is used to control neuronal activity and behavior in mice.

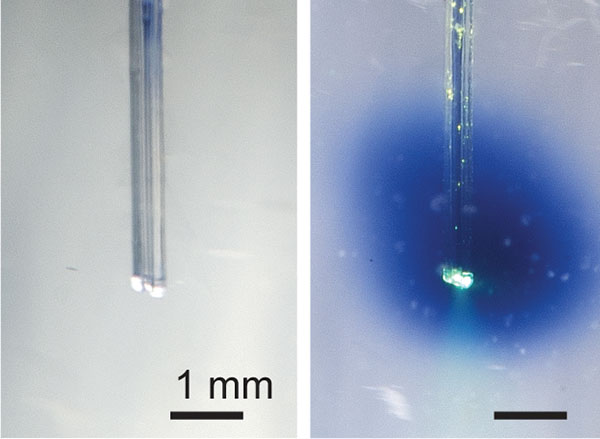

To use light to control drug activity, light and drugs must be delivered simultaneously to the targeted cells. This is a major challenge when the target is deep in the body, but Anikeeva’s Bioelectronics group is uniquely equipped to deal with this challenge. Marc-Joseph (MJ) Antonini, a PhD student in Anikeeva’s Bioelectronics lab and co-first author of the study, specializes in the fabrication of biocompatible multifunctional fibers that house microfluidic channels and waveguides to deliver liquids and transmit light.

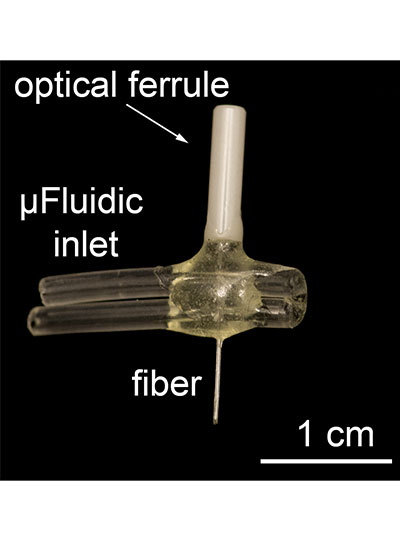

The multifunctional fibers used in this study contain a fluidic channel and an optical waveguide and are comprised of many layers of different materials that are fused together to provide flexibility and strength. The original form of the fiber is constructed at a macroscale and then heated and pulled (a process called thermal drawing) to become longer, but nearly 70X smaller in diameter. By this method, 100’s of meters of miniaturized fiber can be created from the original template at a cross-sectional scale of micrometers that minimizes tissue damage.

The device used in this study had an implantable fiber bundle of 480µm × 380µm and weighed only 0.8 g, small enough that a mouse can easily carry it on its head for many weeks.

To demonstrate effectiveness of their device for simultaneous delivery of liquids and light, the Anikeeva lab teamed up with Dirk Trauner (Frank’s former PhD advisor) and David Konrad, pharmacologists who synthesized photoswitchable drugs.

They had previously modified a photoswitchable analog of capsaicin, a molecule found in hot peppers that binds to the TRPV1 receptor on sensory neurons and controls the sensation of heat. This modification allowed the capsaicin analog to be activated by 560 nm wave-length of light (visible green) that is not damaging to tissue compared to the original version of the drug that required ultraviolet light. By adding both the TRPV1 receptor and the new photoswitchable capsaicin analog to neurons, they could be artificially activated with green light.

This new photopharmacology system had been shown by Frank, Konrad and their colleagues to work in cells cultured in a dish, but had never been shown to work in freely-moving animals.

To test whether their system could activate neurons in the brain, Frank and Antonini tested it in mice. They asked whether adding the photoswitchable drug and its receptor to reward-mediating neurons in the mouse brain causes mice to prefer a chamber in which they receive light stimulation.

The miniaturized multifunctional fiber developed by the team was implanted in the mouse brain’s ventral tegmental area, a deep region rich in dopamine neurons that controls reward-seeking behavior. Through the fluidic channel in the device, the researchers delivered a virus that drives expression of the TRPV1 receptor in the neurons under study. Several weeks later, the device was then used to deliver both light and the photoswitchable capsaicin analog directly to the same neurons. To control for the specificity of their system, they also tested the effects of delivering a virus that does not express the TRPV1 receptor, and the effects of delivering a wavelength of light that does not switch on the drug.

They found that mice showed a preference only for the chamber where they had previously received all three components required for the photopharmacology to function: the receptor-expressing virus, the photoswitchable receptor ligand and the green light that activates the drug. These results demonstrate the efficacy of this system to control the time and place within the body that a drug is active.

“Using these fibers to enable photopharmacology in vivo is a great example of how our multifunctional platform can be leveraged to improve and expand how we can interact with the brain,” says Antonini. “This combination of technologies allows us to achieve the temporal and spatial resolution of light stimulation with the chemical specificity of drug injection in freely moving animals.”

Therapeutic drugs that are taken orally or by injection often cause unwanted side-effects because they act continuously and throughout the whole body. Many unwanted side effects could be eliminated by targeting a drug to a specific body tissue and activating it only as needed. The new technology described by Anikeeva and colleagues is one step toward this ultimate goal.

“Our next goal is to use these neural implants to deliver other photoswitchable drugs to target receptors which are naturally expressed within these circuits,” says Frank, whose new lab in the Vollum Institute at OHSU is synthesizing new light-controllable molecules. “The hardware presented in this study will be widely applicable for controlling circuits throughout the brain, enabling neuroscientists to manipulate them with enhanced precision.”

Our ability to pay attention, plan, and trouble-shoot involve cognitive processing by the brain’s prefrontal cortex. The balance of activity among excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the cortex, based on local neural circuits and distant inputs, is key to these cognitive functions.

A recent study from the McGovern Institute shows that excitatory inputs from the thalamus activate a local inhibitory circuit in the prefrontal cortex, revealing new insights into how these cognitive circuits may be controlled.

“For the field, systematic identification of these circuits is crucial in understanding behavioral flexibility and interpreting psychiatric disorders in terms of dysfunction of specific microcircuits,” says postdoctoral associate Arghya Mukherjee, lead author on the report.

The thalamus is located in the center of the brain and is considered a cerebral hub based on its inputs from a diverse array of brain regions and outputs to the striatum, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex. More than 60 thalamic nuclei (cellular regions) have been defined and are broadly divided into “sensory” or “higher-order” thalamic regions based on whether they relay primary sensory inputs or instead have inputs exclusively from the cerebrum.

Considering the fundamental distinction between the input connections of the sensory and higher-order thalamus, Mukherjee, a researcher in the lab of Michael Halassa, the Class of 1958 Career Development Professor in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, decided to explore whether there are similarly profound distinctions in their outputs to the cerebral cortex.

He addressed this question in mice by directly comparing the outputs of the medial geniculate body (MGB), a sensory thalamic region, and the mediodorsal thalamus (MD), a higher-order thalamic region. The researchers selected these two regions because the relatively accessible MGB nucleus relays auditory signals to cerebral cortical regions that process sound, and the MD interconnects regions of the prefrontal cortex.

Their study, now available as a preprint in eLife, describes key functional and anatomical differences between these two thalamic circuits. These findings build on Halassa’s previous work showing that outputs from higher-order thalamic nuclei play a central role in cognitive processing.

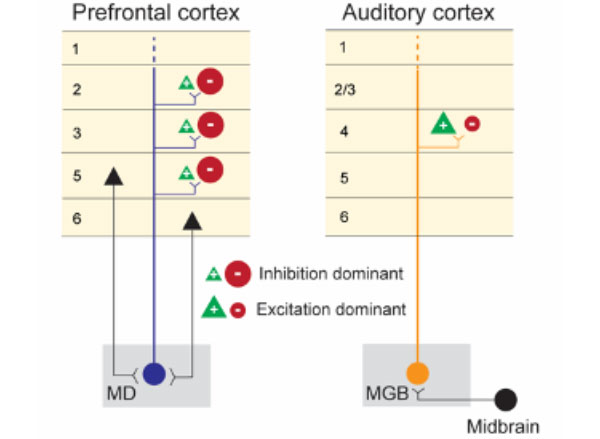

Using cutting-edge stimulation and recording methods, the researchers found that neurons in the prefrontal and auditory cortices have dramatically different responses to activation of their respective MD and MGB inputs.

The researchers stimulated the MD-prefrontal and MGB-auditory cortex circuits using optogenetic technology and recorded the response to this stimulation with custom multi-electrode scaffolds that hold independently movable micro-drives for recording hundreds of neurons in the cortex. When MGB neurons were stimulated with light, there was strong activation of neurons in the auditory cortex. By contrast, MD stimulation caused a suppression of neuron firing in the prefrontal cortex and concurrent activation of local inhibitory interneurons. The separate activation of the two thalamocortical circuits had dramatically different impacts on cortical output, with the sensory thalamus seeming to promote feed-forward activity and the higher-order thalamus stimulating inhibitory microcircuits within the cortical target region.

“The textbook view of the thalamus is an excitatory cortical input, and the fact that turning on a thalamic circuit leads to a net cortical inhibition was quite striking and not something you would have expected based on reading the literature,” says Halassa, who is also an associate investigator at the McGovern Institute. “Arghya and his colleagues did an amazing job following that up with detailed anatomy to explain why might this effect be so.”

Using a system called GFP (green fluorescent protein) reconstitution across synaptic partners (mGRASP), the researchers demonstrated that MD and MGB projections target different types of cortical neurons, offering a possible explanation for their differing effects on cortical activity.

With mGRASP, the presynaptic terminal (in this case, MD or MGB) expresses one part of the fluorescent protein and the postsynaptic neuron (in this case, prefrontal or auditory cortex) expresses the other part of the fluorescent protein, which by themselves alone do not fluoresce. Only when there is a close synaptic connection do the two parts of GFP come together to become fluorescent. These experiments showed that MD neurons synapse more frequently onto inhibitory interneurons in the prefrontal cortex whereas MGB neurons synapse onto excitatory neurons with larger synapses, consistent with only MGB being a strong activity driver.

Using fluorescent viral vectors that can cross synapses of interconnected neurons, a technology developed by McGovern principal research scientist Ian Wickersham, the researchers were also able to map the inputs to the MD and MGB thalamic regions. Viruses, like rabies, are well-suited for tracing neural connections because they have evolved to spread from neuron to neuron through synaptic junctions.

The inputs to the targeted higher-order and sensory thalamocortical neurons identified across the brain appeared to arise respectively from forebrain and midbrain sensory regions, as expected. The MGB inputs were consistent with a sensory relay function, arising primarily from the auditory input pathway. By contrast, MD inputs arose from a wide array of cerebral cortical regions and basal ganglia circuits, consistent with MD receiving contextual and motor command information.

By directly comparing these microcircuits, the Halassa lab has revealed important clues about the function and anatomy of these sensory and higher-order brain connections. It is only through a systematic understanding of these circuits that we can begin to interpret how their dysfunction may contribute to psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia.

It is this basic scientific inquiry that often fuels their research, says Halassa. “Excitement about science is part of the glue that holds us all together.”

Robert Desimone, the Doris and Don Berkey Professor in Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, has been recognized by the Cognitive Neuroscience Society as this year’s winner of the Fred Kavli Distinguished Career Contributions (DCC) award. Supported annually by the Kavli Foundation, the award honors senior cognitive neuroscientists for their distinguished career, leadership and mentoring in the field of cognitive neuroscience.

Desimone, who is also the director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, studies the brain mechanisms underlying attention, and most recently, has been studying animal models for brain disorders.

Desimone will deliver his prize lecture at the annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society in March 2021.

As cells grow, divide, and respond to their environment, their gene expression changes; one gene may be transcribed into more RNA at one time point and less at another time when it’s no longer needed. Now, researchers at the McGovern Institute, Harvard, and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have developed a way to determine when specific RNA molecules are produced in cells. The method, described today in Nature Biotechnology, allows scientists to more easily study how a cell’s gene expression fluctuates over time.

“Biology is very dynamic but most of the tools we use in biology are static; you get a fixed snapshot of what’s happening in a cell at a given moment,” said Fei Chen, a core institute member at the Broad, an assistant professor at Harvard University, and a co-senior author of the new work. “This will now allow us to record what’s happening over hours or days.”

To find out the level of RNA a cell is transcribing, researchers typically extract genetic material from the cell—destroying the cell in the process—and use RNA sequencing technology to determine which genes are being transcribed into RNA, and how much. Although researchers can sample cells at various times, they can’t easily measure gene expression at multiple time points.

To create a more precise timestamp, the team added strings of repetitive DNA bases to genes of interest in cultured human cells. These strings caused the cell to add repetitive regions of adenosine molecules—one of four building blocks of RNA — to the ends of RNA when the RNA was transcribed from these genes. The researchers also introduced an engineered version of an enzyme called adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR2cd), which slowly changed the adenosine molecules to a related molecule, inosine, at a predictable rate in the RNA. By measuring the ratio of inosines to adenosines in the timestamped section of any given RNA molecule, the researchers could elucidate when it was first produced, while keeping cells intact.

“It was pretty surprising to see how well this worked as a timestamp,” said Sam Rodriques, a co-first author of the new paper and former MIT graduate student who is now founding the Applied Biotechnology Laboratory at the Crick Institute in London. “And the more molecules you look at, the better your temporal resolution.”

Using their method, the researchers could estimate the age of a single timestamped RNA molecule to within 2.7 hours. But when they looked simultaneously at four RNA molecules, they could estimate the age of the molecules to within 1.5 hours. Looking at 200 molecules at once allowed the scientists to correctly sort RNA molecules into groups based on their age, or order them along a timeline with 86 percent accuracy.

“Extremely interesting biology, such as immune responses and development, occurs over a timescale of hours,” said co-first author of the paper Linlin Chen of the Broad. “Now we have the opportunity to better probe what’s happening on this timescale.”

The researchers found that the approach, with some small tweaks, worked well on various cell types — neurons, fibroblasts and embryonic kidney cells. They’re planning to now use the method to study how levels of gene activity related to learning and memory change in the hours after a neuron fires.

The current system allows researchers to record changes in gene expression over half a day. The team is now expanding the time range over which they can record gene activity, making the method more precise, and adding the ability to track several different genes at a time.

“Gene expression is constantly changing in response to the environment,” said co-senior author Edward Boyden of MIT, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “Tools like this will help us eavesdrop on how cells evolve over time, and help us pinpoint new targets for treating diseases.”

Support for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Schmidt Fellows Program at Broad Institute, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, John Doerr, the Open Philanthropy Project, the HHMI-Simons Faculty Scholars Program, the U. S. Army Research Laboratory and the U. S. Army Research Office, the MIT Media Lab, Lisa Yang, the Hertz Graduate Fellowship and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

MIT researchers have identified a brain pathway critical in enabling primates to effortlessly identify objects in their field of vision. The findings enrich existing models of the neural circuitry involved in visual perception and help to further unravel the computational code for solving object recognition in the primate brain.

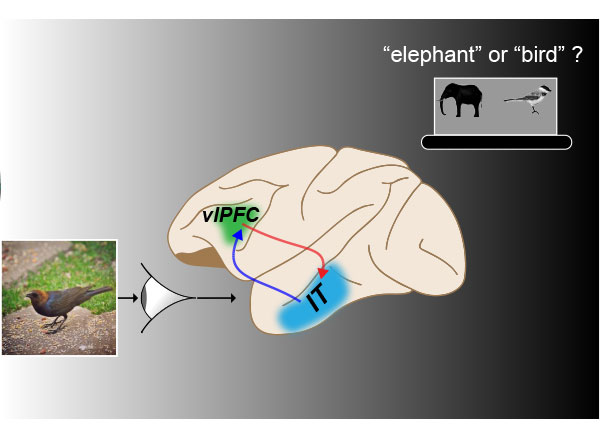

Led by Kohitij Kar, a postdoctoral associate at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, the study looked at an area called the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), which sends feedback signals to the inferior temporal (IT) cortex via a network of neurons. The main goal of this study was to test how the back and forth information processing of this circuitry, that is, this recurrent neural network, is essential to rapid object identification in primates.

The current study, published in Neuron and available today via open access, is a follow-up to prior work published by Kar and James DiCarlo, Peter de Florez Professor of Neuroscience, the head of MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and an investigator in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines.

In 2019, Kar, DiCarlo, and colleagues identified that primates must use some recurrent circuits during rapid object recognition. Monkey subjects in that study were able to identify objects more accurately than engineered “feedforward” computational models, called deep convolutional neural networks, that lacked recurrent circuitry.

Interestingly, specific images for which models performed poorly compared to monkeys in object identification, also took longer to be solved in the monkeys’ brains — suggesting that the additional time might be due to recurrent processing in the brain. Based on the 2019 study, it remained unclear though exactly which recurrent circuits were responsible for the delayed information boost in the IT cortex. That’s where the current study picks up.

“In this new study, we wanted to find out: Where are these recurrent signals in IT coming from?” Kar said. “Which areas reciprocally connected to IT, are functionally the most critical part of this recurrent circuit?”

To determine this, researchers used a pharmacological agent to temporarily block the activity in parts of the vlPFC in macaques while they engaged in an object discrimination task. During these tasks, monkeys viewed images that contained an object, such as an apple, a car, or a dog; then, researchers used eye tracking to determine if the monkeys could correctly indicate what object they had previously viewed when given two object choices.

“We observed that if you use pharmacological agents to partially inactivate the vlPFC, then both the monkeys’ behavior and IT cortex activity deteriorates but more so for certain specific images. These images were the same ones we identified in the previous study — ones that were poorly solved by ‘feedforward’ models and took longer to be solved in the monkey’s IT cortex,” said Kar.

“These results provide evidence that this recurrently connected network is critical for rapid object recognition, the behavior we’re studying. Now, we have a better understanding of how the full circuit is laid out, and what are the key underlying neural components of this behavior.”

The full study, entitled “Fast recurrent processing via ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is needed by the primate ventral stream for robust core visual object recognition,” will run in print January 6, 2021.

“This study demonstrates the importance of pre-frontal cortical circuits in automatically boosting object recognition performance in a very particular way,” DiCarlo said. “These results were obtained in nonhuman primates and thus are highly likely to also be relevant to human vision.”

The present study makes clear the integral role of the recurrent connections between the vlPFC and the primate ventral visual cortex during rapid object recognition. The results will be helpful to researchers designing future studies that aim to develop accurate models of the brain, and to researchers who seek to develop more human-like artificial intelligence.

Neuropsychiatric illnesses like schizophrenia and autism are a complex interplay of brain chemicals, environment, and genetics that requires careful study to understand the root causes. Scientists have traditionally relied on samples taken from mice and non-human primates to study how these diseases develop. But the question has lingered: are the brains of these subjects similar enough to humans to yield useful insights?

Now work from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research is pointing towards an answer. In a study published in Nature, researchers from the Broad’s Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research report several key differences in the brains of ferrets, mice, nonhuman primates, and humans, all focused on a type of neuron called interneurons. Most surprisingly, the team found a new type of interneuron only in primates, located in a part of the brain called the striatum, which is associated with Huntington’s disease and potentially schizophrenia.

The findings could help accelerate research into causes of and treatments for neuropsychiatric illnesses, by helping scientists choose the lab model that best mimics features of the human brain that may be involved in these diseases.

“The data from this work will inform the study of human brain disorders because it helps us think about which features of the human brain can be studied in mice, which features require higher organisms such as marmosets, and why mouse models often don’t reflect the effects of the corresponding mutations in human,” said Steven McCarroll, senior author of the study, director of genetics at the Stanley Center, and a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School.

“Dysfunctions of interneurons have been strongly linked to several brain disorders including autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia,” said Guoping Feng, co-author of the study, director of model systems and neurobiology at the Stanley Center, and professor of neuroscience at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “These data further demonstrate the unique importance of non-human primate models in understanding neurobiological mechanisms of brain disorders and in developing and testing therapeutic approaches.”

Interneurons form key nodes within neural circuitry in the brain, and help regulate neuronal activity by releasing the neurotransmitter GABA, which inhibits the firing of other neurons.

Fenna Krienen, a postdoctoral fellow in the McCarroll Lab and first author on the Nature paper, and her colleagues wanted to track the natural history of interneurons.

“We wanted to gain an understanding of the evolutionary trajectory of the cell types that make up the brain,” said Krienen. “And then we went about acquiring samples from species that could inform this understanding of evolutionary divergence between humans and the models that so often stand in for humans in neuroscience studies.”

One of the tools the researchers used was Drop-seq, a high-throughput single nucleus RNA sequencing technique developed by McCarroll’s lab, to classify the roles and locations of more than 184,000 telencephalic interneurons in the brains of ferrets, humans, macaques, marmosets, and mice. Using tissue from frozen samples, the team isolated the nuclei of interneurons from the cortex, the hippocampus, and the striatum, and profiled the RNA from the cells.

The researchers thought that because interneurons are found in all vertebrates, the cells would be relatively static from species to species.

“But with these sensitive measurements and a lot of data from the various species, we got a different picture about how lively interneurons are, in terms of the ways that evolution has tweaked their programs or their populations from one species to the next,” said Krienen.

She and her collaborators identified four main differences in interneurons between the species they studied: the cells change their proportions across brain regions, alter the programs they use to link up with other neurons, and can migrate to different regions of the brain.

But most strikingly, the scientists discovered that primates have a novel interneuron not found in other species. The interneuron is located in the striatum—the brain structure responsible for cognition, reward, and coordinated movements that has existed as far back on the evolutionary tree as ancient primitive fish. The researchers were amazed to find the new neuron type made up a third of all interneurons in the striatum.

“Although we expected the big innovations in human and primate brains to be in the cerebral cortex, which we tend to associate with human intelligence, it was in fact in the venerable striatum that Fenna uncovered the most dramatic cellular innovation in the primate brain,” said McCarroll. “This cell type had never been discovered before, because mice have nothing like it.”

“The question of what provides the “human advantage” in cognitive abilities is one of the fundamental issues neurobiologists have endeavored to answer,” said Gordon Fishell, group leader at the Stanley Center, a professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School, and a collaborator on the study. “These findings turn on end the question of ‘how do we build better brains?’. It seems at least part of the answer stems from creating a new list of parts.”

A better understanding of how these inhibitory neurons vary between humans and lab models will provide researchers with new tools for investigating various brain disorders. Next, the researchers will build on this work to determine the specific functions of each type of interneuron.

“In studying neurodevelopmental disorders, you would like to be convinced that your model is an appropriate one for really complex social behaviors,” Krienen said. “And the major overarching theme of the study was that primates in general seem to be very similar to one another in all of those interneuron innovations.”

Support for this work was provided in part by the Broad Institute’s Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research and the NIH Brain Initiative, the Dean’s Innovation Award (Harvard Medical School), the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research at MIT, the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Pat and Lore McGovern founded the McGovern Institute 20 years ago with a dual mission – to understand the brain, and to apply that knowledge to help the many people affected by brain disorders. Some of the amazing developments of the past 20 years, such as CRISPR, may seem entirely unexpected and “out of the blue.” But they were all built on a foundation of basic research spanning many years. With the incredible foundation we are building right now, I feel we are poised for many more “unexpected” discoveries in the years ahead.

I predict that in 20 years, we will have quantitative models of brain function that will not only explain how the brain gives rise to at least some aspects of our mind, but will also give us a new mechanistic understanding of brain disorders. This, in turn, will lead to new types of therapies, in what I imagine to be a post-pharmaceutical era of the future. I have no doubt that these same brain models will inspire new educational approaches for our children, and will be incorporated into whatever replaces my automobile, and iPhone, in 2040. I encourage you to read some other predictions from our faculty.

Our cutting-edge work depends not only on our stellar line up of faculty, but the more than 400 postdocs, graduate students, undergraduates, summer students, and staff who make up our community.

For this reason, I am particularly delighted to share with you McGovern’s rising stars — 20 young scientists from each of our labs — who represent the next generation of neuroscience.

And finally, we remain deeply indebted to our supporters for funding our research, including ongoing support from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. In recent years, more than 40% of our annual research funding has come from private individuals and foundations. This support enables critical seed funding for new research projects, the development of new technologies, our new research into autism and psychiatric disorders, and fellowships for young scientists just starting their careers. Our annual fund supporters have made possible more than 42 graduate fellowships, and you can read about some of these fellows on our website.

I hope that as you visit our website and read the pages of our special anniversary issue of Brain Scan, you will feel as optimistic as I do about our future.

Robert Desimone

Director, McGovern Institute

Doris and Don Berkey Professor of Neuroscience

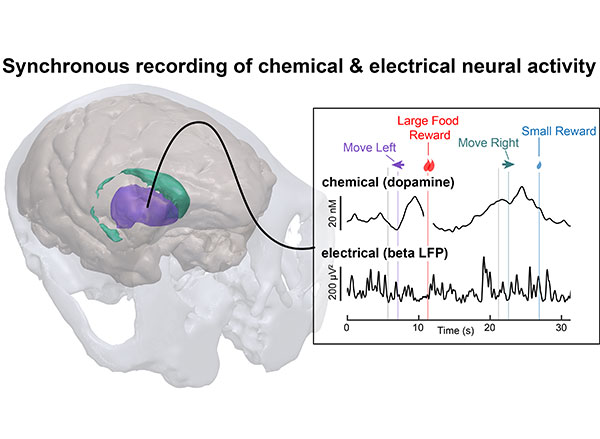

As the brain processes information, electrical charges zip through its circuits and neurotransmitters pass molecular messages from cell to cell. Both forms of communication are vital, but because they are usually studied separately, little is known about how they work together to control our actions, regulate mood, and perform the other functions of a healthy brain.

Neuroscientists in Ann Graybiel’s laboratory at MIT’s McGovern Institute are taking a closer look at the relationship between these electrical and chemical signals. “Considering electrical signals side by side with chemical signals is really important to understand how the brain works,” says Helen Schwerdt, a postdoctoral researcher in Graybiel’s lab. Understanding that relationship is also crucial for developing better ways to diagnose and treat nervous system disorders and mental illness, she says, noting that the drugs used to treat these conditions typically aim to modulate the brain’s chemical signaling, yet studies of brain activity are more likely to focus on electrical signals, which are easier to measure.

Schwerdt and colleagues in Graybiel’s lab have developed new tools so that chemical and electrical signals can, for the first time, be measured simultaneously in the brains of primates. In a study published September 25, 2020, in Science Advances, they used those tools to reveal an unexpectedly complex relationship between two types of signals that are disrupted in patients with Parkinson’s disease—dopamine signaling and coordinated waves of electrical activity known as beta-band oscillations.

Graybiel’s team focused its attention on beta-band activity and dopamine signaling because studies of patients with Parkinson’s disease had suggested a straightforward inverse relationship between the two. The tremors, slowness of movement, and other symptoms associated with the disease develop and progress as the brain’s production of the neurotransmitter dopamine declines, and at the same time, beta-band oscillations surge to abnormal levels. Beta-band oscillations are normally observed in parts of the brain that control movement when a person is paying attention or planning to move. It’s not clear what they do or why they are disrupted in patients with Parkinson’s disease. But because patients’ symptoms tend to be worst when beta activity is high—and because beta activity can be measured in real time with sensors placed on the scalp or with a deep-brain stimulation device that has been implanted for treatment, researchers have been hopeful that it might be useful for monitoring the disease’s progression and patients’ response to treatment. In fact, clinical trials are already underway to explore the effectiveness of modulating deep-brain stimulation treatment based on beta activity.

When Schwerdt and colleagues examined these two types of signals in the brains of rhesus macaques, they discovered that the relationship between beta activity and dopamine is more complicated than previously thought.

Their new tools allowed them to simultaneously monitor both signals with extraordinary precision, targeting specific parts of the striatum—a region deep within the brain involved in controlling movement, where dopamine is particularly abundant—and taking measurements on the millisecond time scale to capture neurons’ rapid-fire communications.

They took these measurements as the monkeys performed a simple task, directing their gaze in a particular direction in anticipation of a reward. This allowed the researchers to track chemical and electrical signaling during the active, motivated movement of the animals’ eyes. They found that beta activity did increase as dopamine signaling declined—but only in certain parts of the striatum and during certain tasks. The reward value of a task, an animal’s past experiences, and the particular movement the animal performed all impacted the relationship between the two types of signals.

“What we expected is there in the overall view, but if we just look at a different level of resolution, all of a sudden the rules don’t hold,” says Graybiel, who is also an MIT Institute Professor. “It doesn’t destroy the likelihood that one would want to have a treatment related to this presumed opposite relationship, but it does say there’s something more here that we haven’t known about.”

The researchers say it’s important to investigate this more nuanced relationship between dopamine signaling and beta activity, and that understanding it more deeply might lead to better treatments for patients with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. While they plan to continue to examine how the two types of signals relate to one another across different parts of the brain and under different behavioral conditions, they hope that other teams will also take advantage of the tools they have developed. “As these methods in neuroscience become more and more precise and dazzling in their power, we’re bound to discover new things,” says Graybiel.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Army Research Office, the Saks Kavanaugh Foundation, the National Science Foundation, Kristin R. Pressman and Jessica J. Pourian ’13 Fund, and Robert Buxton.

Robert Desimone, the Doris and Don Berkey Professor in Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, has been named a winner of this year’s Goldman-Rakic Prize for Outstanding Achievement in Cognitive Neuroscience Research. The award, given annually by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, is named in recognition of former Yale University neuroscientist Patricia Goldman-Rakic.

Desimone, who is also the director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, studies the brain mechanisms underlying attention, and most recently he has been studying animal models for brain disorders.

Desimone will deliver his prize lecture at the 2020 Annual International Mental Health Research Virtual Symposium on October 30, 2020.