The McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT announced today that Huda Y. Zoghbi, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, is the winner of the 2014 Edward M. Scolnick Prize in Neuroscience. The Prize is awarded annually by the McGovern Institute to recognize outstanding advances in the field of neuroscience.

“Huda Zoghbi has been a pioneer in the study of human genetic disease,” says Robert Desimone, director of the McGovern Institute and chair of the selection committee. “Her work has provided fundamental insights into the mechanisms of hereditary neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases, and has pointed the way to new treatments for these disorders.”

Zoghbi studied medicine in her native Lebanon and later in the US, where she specialized in pediatric neurology. Following her residency she trained as a molecular geneticist with Arthur Beaudet at Baylor College of Medicine, where she became a faculty member in 1988. She is currently an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Zoghbi’s first major scientific contribution was the identification in 1993 of the gene responsible for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), a progressive neurodegenerative disease with an unusual pattern of inheritance. In collaboration with Harry Orr at the University of Minnesota, Zoghbi showed that SCA1, like Huntington’s disease, is caused by a pathological expansion of a repeated three-nucleotide sequence. The more times this is repeated, the earlier the onset of disease and the more severe the symptoms. The number of repeats can increase from one generation to the next, meaning that children are often more severely affected than the parent. Zoghbi continues to study SCA1, and her recent work has focused on identifying genetic factors that slow the progression of the disease, a strategy that she hopes will also be applicable to other neurodegenerative disorders.

Zoghbi is perhaps best known for her pioneering work on Rett syndrome, a genetic neurological disease that affects young girls (males with the condition usually die in infancy). Girls born with the disease develop normally for one or two years, but then begin to show progressive loss of motor skills, speech, and other cognitive abilities.

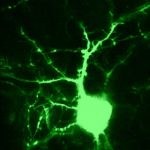

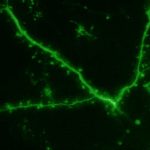

Zoghbi first encountered children with Rett syndrome during her residency, and decided to search for its genetic cause. This was a challenging task; the disease was not widely recognized at the time and was often misdiagnosed, and family studies were difficult because the majority of cases were caused by isolated sporadic mutations. Zoghbi persisted despite these challenges, and after a 16-year search, she succeeded in identifying the Rett gene in 1999. This discovery provided a definitive genetic diagnosis for the condition, and also opened the door to a biological understanding and a search for treatment. Zoghbi demonstrated that Rett syndrome is caused by deficiency in a protein called MeCP2, which binds methylated DNA and regulates the expression of many other genes. The gene lies on the X chromosome, and in females one of the two X chromosomes is randomly inactivated in each cell; thus each patient with the Rett mutation has a different pattern of healthy and mutant cells, explaining some of the variability of Rett symptoms.

Identification of the Rett gene allowed researchers to make equivalent mutations in mouse models, which develop progressive neurological symptoms strikingly similar to those of human patients. This in turn laid the groundwork for further studies by Zoghbi and many other labs, and to the development of new therapeutic strategies that are now undergoing clinical trials.

The implications of this work extend beyond Rett syndrome (a relatively rare condition). Many Rett patients show symptoms of autism, and one hope is that understanding these symptoms may lead to new treatments that will be effective not only for people with Rett syndrome but also for other more common cases of autism. Zoghbi’s recent work has focused on identifying the cell types and brain circuits that are responsible for the autistic-like behaviors of the mouse Rett model, which may represent promising targets for future therapeutic intervention.

In addition to running her own laboratory, Zoghbi is the founding director of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital. She has received numerous awards and honors for her work, including election to both the Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences.

The McGovern Institute will award the Scolnick Prize to Dr. Zoghbi on Wednesday April 30, 2014. At 4:00 pm she will deliver a lecture entitled “A neural tipping point: MeCP2 and neuropsychiatric disorders,” to be followed by a reception, at the McGovern Institute in the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Complex, 43 Vassar Street (building 46, room 3002) in Cambridge. The event is free and open to the public.

About the Edward M. Scolnick Prize in Neuroscience:

The Scolnick Prize, awarded annually by the McGovern Institute, is named in honor of Dr. Edward M. Scolnick, who stepped down as President of Merck Research Laboratories in December 2002 after holding Merck’s top research post for 17 years. Dr. Scolnick is now a core member of the Broad Institute, where he is chief scientist at the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research. He also serves as a member of the McGovern Institute’s governing board. The prize, which is endowed through a gift from Merck to the McGovern Institute, consists of a $100,000 award, plus an inscribed gift. Previous winners are Thomas Jessell (Columbia University), Roger Nicoll (University of California, San Francisco), Bruce McEwen (Rockefeller University), Lily and Yuh-Nung Jan (University of California, San Francisco), Jeremy Nathans (Johns Hopkins University), Michael Davis (Emory University), David Julius (University of California, San Francisco), Michael Greenberg (Harvard Medical School), Judith Rapoport (National Institute of Mental Health) and Mark Konishi (California Institute of Technology).