Abnormal levels of stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol are linked to a variety of mental health disorders, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). MIT researchers have now devised a way to remotely control the release of these hormones from the adrenal gland, using magnetic nanoparticles.

This approach could help scientists to learn more about how hormone release influences mental health, and could eventually offer a new way to treat hormone-linked disorders, the researchers say.

“We’re looking how can we study and eventually treat stress disorders by modulating peripheral organ function, rather than doing something highly invasive in the central nervous system,” says Polina Anikeeva, an MIT professor of materials science and engineering and of brain and cognitive sciences.

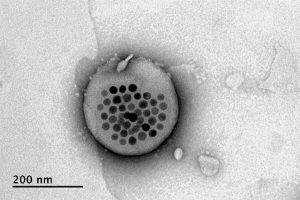

To achieve control over hormone release, Dekel Rosenfeld, an MIT-Technion postdoc in Anikeeva’s group, has developed specialized magnetic nanoparticles that can be injected into the adrenal gland. When exposed to a weak magnetic field, the particles heat up slightly, activating heat-responsive channels that trigger hormone release. This technique can be used to stimulate an organ deep in the body with minimal invasiveness.

Anikeeva and Alik Widge, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota and a former research fellow at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, are the senior authors of the study. Rosenfeld is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Science Advances.

Controlling hormones

Anikeeva’s lab has previously devised several novel magnetic nanomaterials, including particles that can release drugs at precise times in specific locations in the body.

In the new study, the research team wanted to explore the idea of treating disorders of the brain by manipulating organs that are outside the central nervous system but influence it through hormone release. One well-known example is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates stress response in mammals. Hormones secreted by the adrenal gland, including cortisol and adrenaline, play important roles in depression, stress, and anxiety.

“Some disorders that we consider neurological may be treatable from the periphery, if we can learn to modulate those local circuits rather than going back to the global circuits in the central nervous system,” says Anikeeva, who is a member of MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics and McGovern Institute for Brain Research.

As a target to stimulate hormone release, the researchers decided on ion channels that control the flow of calcium into adrenal cells. Those ion channels can be activated by a variety of stimuli, including heat. When calcium flows through the open channels into adrenal cells, the cells begin pumping out hormones. “If we want to modulate the release of those hormones, we need to be able to essentially modulate the influx of calcium into adrenal cells,” Rosenfeld says.

Unlike previous research in Anikeeva’s group, in this study magnetothermal stimulation was applied to modulate the function of cells without artificially introducing any genes.

To stimulate these heat-sensitive channels, which naturally occur in adrenal cells, the researchers designed nanoparticles made of magnetite, a type of iron oxide that forms tiny magnetic crystals about 1/5000 the thickness of a human hair. In rats, they found these particles could be injected directly into the adrenal glands and remain there for at least six months. When the rats were exposed to a weak magnetic field — about 50 millitesla, 100 times weaker than the fields used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) — the particles heated up by about 6 degrees Celsius, enough to trigger the calcium channels to open without damaging any surrounding tissue.

The heat-sensitive channel that they targeted, known as TRPV1, is found in many sensory neurons throughout the body, including pain receptors. TRPV1 channels can be activated by capsaicin, the organic compound that gives chili peppers their heat, as well as by temperature. They are found across mammalian species, and belong to a family of many other channels that are also sensitive to heat.

This stimulation triggered a hormone rush — doubling cortisol production and boosting noradrenaline by about 25 percent. That led to a measurable increase in the animals’ heart rates.

Treating stress and pain

The researchers now plan to use this approach to study how hormone release affects PTSD and other disorders, and they say that eventually it could be adapted for treating such disorders. This method would offer a much less invasive alternative to potential treatments that involve implanting a medical device to electrically stimulate hormone release, which is not feasible in organs such as the adrenal glands that are soft and highly vascularized, the researchers say.

Another area where this strategy could hold promise is in the treatment of pain, because heat-sensitive ion channels are often found in pain receptors.

“Being able to modulate pain receptors with this technique potentially will allow us to study pain, control pain, and have some clinical applications in the future, which hopefully may offer an alternative to medications or implants for chronic pain,” Anikeeva says. With further investigation of the existence of TRPV1 in other organs, the technique can potentially be extended to other peripheral organs such as the digestive system and the pancreas.

The research was funded by the U.S. Defense Advance Research Projects Agency ElectRx Program, a Bose Research Grant, the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative, and a MIT-Technion fellowship.