“There’s a slogan in education,” says McGovern Investigator John Gabrieli. “The first three years are learning to read, and after that you read to learn.”

For John Gabrieli, learning to read represents one of the most important milestones in a child’s life. Except, that is, when a child can’t. Children who cannot learn to read adequately by the first grade have a 90 percent chance of still reading poorly in the fourth grade, and 75 percent odds of struggling in high school. For the estimated 10 percent of schoolchildren with a reading disability, that struggle often comes with a host of other social and emotional challenges: anxiety, damaged self-esteem, increased risk for poverty and eventually, encounters with the criminal justice system.

Most reading interventions focus on classical dyslexia, which is essentially a coding problem—trouble moving letters into sound patterns in the brain. But other factors, such as inadequate vocabulary and lack of practice opportunities, hinder reading too. The diagnosis can be subjective, and for those who are diagnosed, the standard treatments help only some students. “Every teacher knows half to two-thirds have a good response, the other third don’t,” Gabrieli says. “It’s a mystery. And amazingly there’s been almost no progress on that.”

For the last two decades, Gabrieli has sought to unravel the neuroscience behind learning and reading disabilities and, ultimately, convert that understanding into new and better education

interventions—a sort of translational medicine for the classroom.

The Home Effect

In 2011, when Julia Leonard was a research assistant in Gabrieli’s lab, she planned to go into pediatrics. But she became drawn to the lab’s education projects and decided to join the lab as

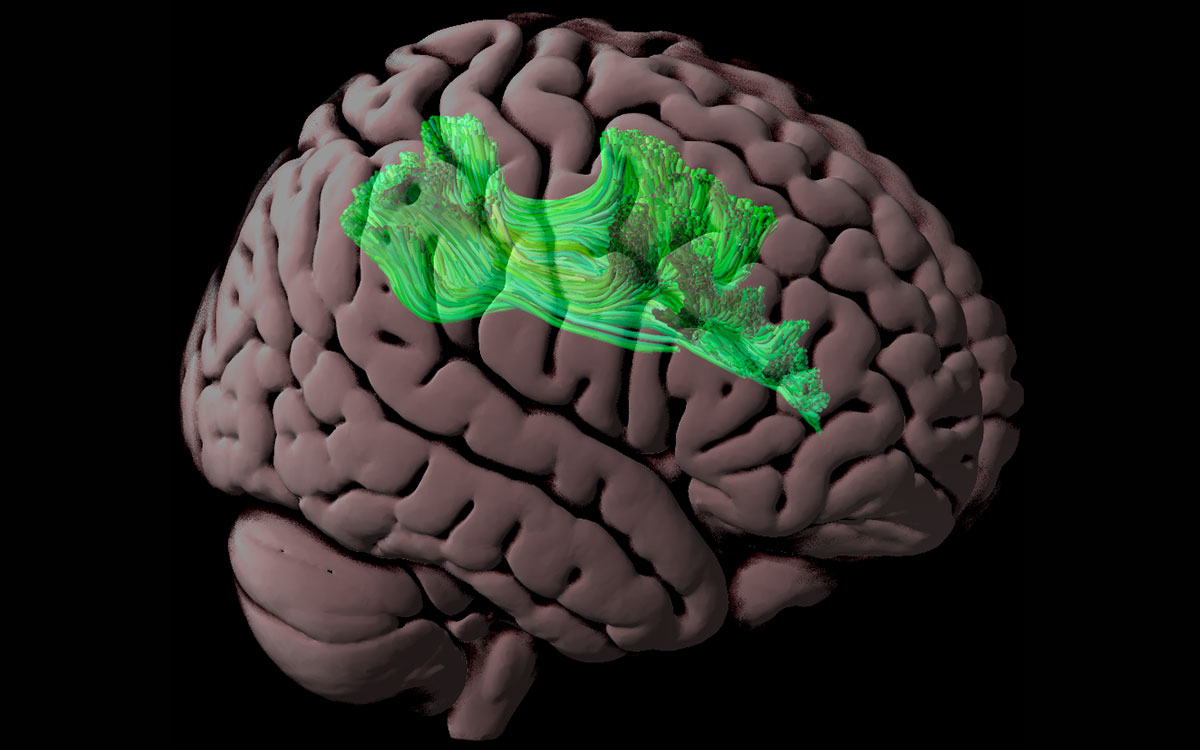

a graduate student to learn more. By 2015, she helped coauthor a landmark study with postdoc Allyson Mackey, that sought neural markers for the academic “achievement gap,” which separates higher socioeconomic status (SES) children from their disadvantaged peers. It was the first study to make a connection between SES-linked differences in brain structure and educational markers. Specifically, they found children from wealthier backgrounds had thicker cortical brain regions, which correlated with better academic achievement.

“Being a doctor is a really awesome and powerful career,” she says. “But I was more curious about the research that could cause bigger changes in children’s lives.”

Leonard collaborated with Rachel Romeo, another graduate student in the Gabrieli lab who wanted to understand the powerful effect of SES on the developing brain. Romeo had a distinctive background in speech pathology and literacy, where she’d observed wealthier students progressing more quickly compared to their disadvantaged peers.

Their research is revealing a fascinating picture. In a 2017 study, Romeo compared how reading-disabled children from low and high SES backgrounds fared after an intensive summer reading intervention. Low SES children in the intervention improved most in their reading, and MRI scans revealed their brains also underwent greater structural changes in response to the intervention. Higher SES children did not appear to change much, either in skill or brain structure.

“In the few studies that have looked at SES effects on treatment outcomes,” Romeo says, “the research suggests that higher SES kids would show the most improvement. We were surprised to

find that this wasn’t true.” She suspects that the midsummer timing of the intervention may account for this. Lower SES kids’ performance often suffer most during a “summer slump,”

and would therefore have the greatest potential to improve from interventions at this time.

However, in another study this year, Leonard uncovered unique brain differences in lower-SES children. Only among lower-SES children was better reasoning ability associated with thicker

cortex in a key part of the brain. Same behavior, different neural signatures.

“So this becomes a really interesting basic science question,” Leonard says. “Does the brain support cognition the same way across everyone, or does it differ based on how you grow up?”

Not a One-Size-Fits-All

Critics of such “educational neuroscience” have highlighted the lack of useful interventions produced by this research. Gabrieli agrees that so far, little has emerged. “The painful thing is the slowness of this work. It’s mind-boggling,” Gabrieli admits. Every intervention requires all the usual human research requirements, plus coordinating with schools, parents, teachers, and so on. “It’s a huge process to do even the smallest intervention,” he explains. Partly because of that, the field is still relatively new.

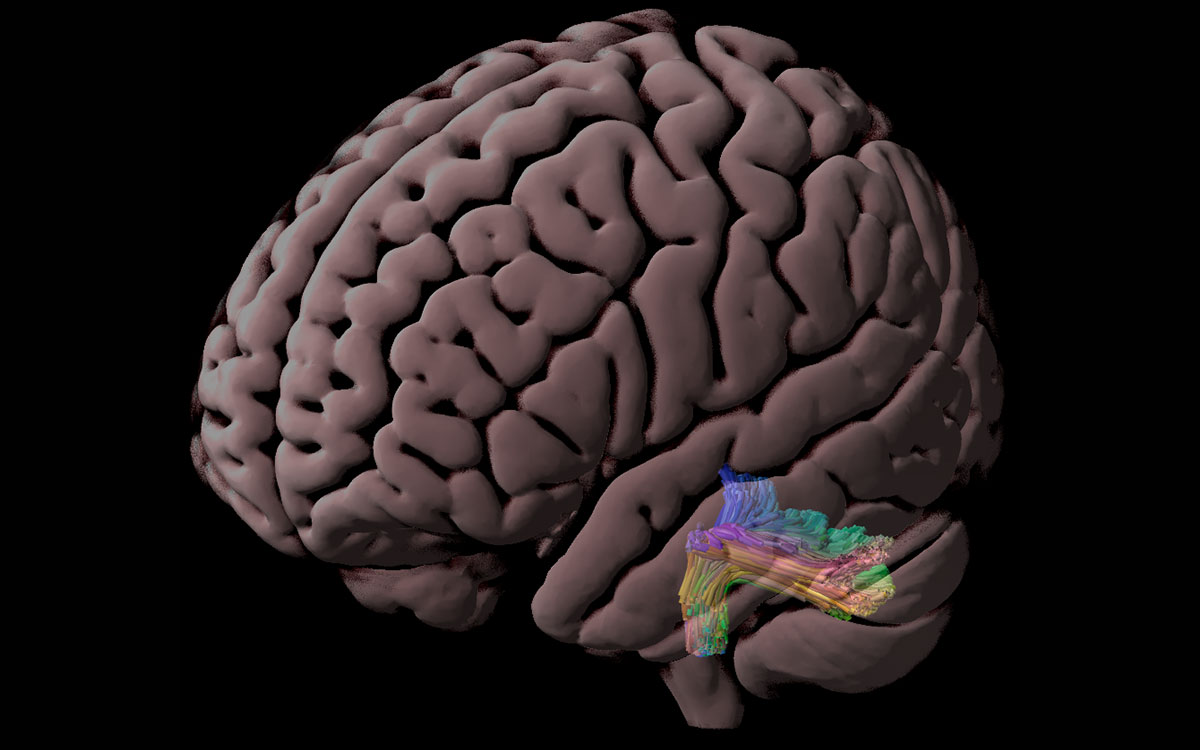

But he disagrees with the idea that nothing will come from this research. Gabrieli’s lab previously identified neural markers in children who will go on to develop reading disabilities. These markers could even predict who would or would not respond to standard treatments that focus on phonetic letter-sound coding.

Romeo and Leonard’s work suggests that varied etiologies underlie reading disabilities, which may be the key. “For so long people have thought that reading disorders were just a unitary construct: kids are bad at reading, so let’s fix that with a one-size-fits-all treatment,” Romeo says.

Such findings may ultimately help resource-strapped schools target existing phonetic training rather than enrolling all struggling readers in the same program, to see some still fail.

Think Spaces

At the Oliver Hazard Perry School, a public K-8 school located on the South Boston waterfront, teachers like Colleen Labbe have begun to independently navigate similar problems as they try

to reach their own struggling students.

“A lot of times we look at assessments and put students in intervention groups like phonics,” Labbe says. “But it’s important to also ask what is happening for these students on their way to school and at home.”

For Labbe and Perry Principal Geoffrey Rose, brain science has proven transformative. They’ve embraced literature on neuroplasticity—the idea that brains can change if teachers find the right combination of intervention and circumstances, like the low-SES students who benefited in Romeo and Leonard’s study.

“A big myth is that the brain can’t grow and change, and if you can’t reach that student, you pass them off,” Labbe says.

The science has also been empowering to her students, validating their own powers of self-change. “I tell the kids, we’re going to build the goop!” she says, referring to the brain’s ability to make new connections.

“All kids can learn,” Rose agrees. “But the flip of that is, can all kids do school?” His job, he says, is to make sure they can.

The classrooms at Perry are a mix of students from different cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds, so he and Labbe have focused on helping teachers find ways to connect with these children and help them manage their stresses and thus be ready to learn. Teachers here are armed with “scaffolds”—digestible neuro- and cognitive science aids culled from Rose’s postdoctoral studies at Boston College’s Professional School Administrator Program for school leaders. These encourage teachers to be more aware of cultural differences and tendencies in themselves and their students, to better connect.

There are also “Think Spaces” tucked into classroom corners. “Take a deep breath and be calm,” read posters at these soothing stations, which are equipped with de-stressing tools, like squeezable balls, play-dough, and meditation-inspiring sparkle wands. It sounds trivial, yet studies have shown that poverty-linked stressors like food and home insecurity take a toll on emotion and memory-linked brain areas like the amygdala and hippocampus.

In fact, a new study by Clemens Bauer, a postdoc in Gabrieli’s lab, argues that mindfulness training can help calm amygdala hyperactivity, help lower self-perceived stress, and boost attention. His study was conducted with children enrolled in a Boston charter school.

Taking these combined approaches, Labbe says, she’s seen one of her students rise from struggling at the lowest levels of instruction, to thriving by year end. Labbe’s focus on understanding the girl’s stressors, her family environment, and what social and emotional support she really needed was key. “Now she knows she can do it,” Labbe says.

Rose and Labbe only wish they could better bridge the gap between educators like themselves and brain scientists like Gabrieli. To help forge these connections, Rose recently visited Gabrieli’s lab and looks forward to future collaborations. Brain research will provide critical insights into teaching strategy, he says, but the gap is still wide.

From Lab to Classroom

“I’m hugely impressed by principals and teachers who are passionately interested in understanding the brain,” Gabrieli says. Fortunately, new efforts are bridging educators and scientists.

This March, Gabrieli and the MIT Integrated Learning Initiative—MITili, which he also directs—announced a $30 million-dollar grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative for a collaboration

between MIT, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Florida State University.

The grant aims to translate some of Gabrieli’s work into more classrooms. Specifically, he hopes to produce better diagnostics that can identify children at risk for dyslexia and other learning

disabilities before they even learn to read.

He hopes to also provide rudimentary diagnostics that identify the source of struggle, be it classic dyslexia, lack of home support, stress, or maybe a combination of factors. That in turn,

could guide treatment—standard phonetic care for some children, versus alternatives: social support akin to Labbe’s efforts, reading practice, or maybe just vocabulary-boosting conversation time with adults.

“We want to get every kid to be an adequate reader by the end of the third grade,” Gabrieli says. “That’s the ultimate goal for me: to help all children become learners.”