People with autism often experience hypersensitivity to noise and other sensory input. MIT neuroscientists have now identified two brain circuits that help tune out distracting sensory information, and they have found a way to reverse noise hypersensitivity in mice by boosting the activity of those circuits.

One of the circuits the researchers identified is involved in filtering noise, while the other exerts top-down control by allowing the brain to switch its attention between different sensory inputs.

The researchers showed that restoring the function of both circuits worked much better than treating either circuit alone. This demonstrates the benefits of mapping and targeting multiple circuits involved in neurological disorders, says Michael Halassa, an assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research.

“We think this work has the potential to transform how we think about neurological and psychiatric disorders, [so that we see them] as a combination of circuit deficits,” says Halassa, the senior author of the study. “The way we should approach these brain disorders is to map, to the best of our ability, what combination of deficits are there, and then go after that combination.”

MIT postdoc Miho Nakajima and research scientist L. Ian Schmitt are the lead authors of the paper, which appears in Neuron on Oct. 21. Guoping Feng, the James W. and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience and a member of the McGovern Institute, is also an author of the paper.

Hypersensitivity

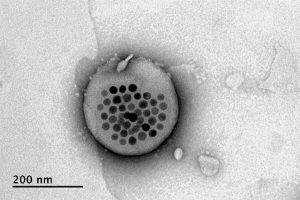

Many gene variants have been linked with autism, but most patients have very few, if any, of those variants. One of those genes is ptchd1, which is mutated in about 1 percent of people with autism. In a 2016 study, Halassa and Feng found that during development this gene is primarily expressed in a part of the thalamus called the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN).

That study revealed that neurons of the TRN help the brain to adjust to changes in sensory input, such as noise level or brightness. In mice with ptchd1 missing, TRN neurons fire too fast, and they can’t adjust when noise levels change. This prevents the TRN from performing its usual sensory filtering function, Halassa says.

“Neurons that are there to filter out noise, or adjust the overall level of activity, are not adapting. Without the ability to fine-tune the overall level of activity, you can get overwhelmed very easily,” he says.

In the 2016 study, the researchers also found that they could restore some of the mice’s noise filtering ability by treating them with a drug called EBIO that activates neurons’ potassium channels. EBIO has harmful cardiac side effects so likely could not be used in human patients, but other drugs that boost TRN activity may have a similar beneficial effect on hypersensitivity, Halassa says.

In the new Neuron paper, the researchers delved more deeply into the effects of ptchd1, which is also expressed in the prefrontal cortex. To explore whether the prefrontal cortex might play a role in the animals’ hypersensitivity, the researchers used a task in which mice have to distinguish between three different tones, presented with varying amounts of background noise.

Normal mice can learn to use a cue that alerts them whenever the noise level is going to be higher, improving their overall performance on the task. A similar phenomenon is seen in humans, who can adjust better to noisier environments when they have some advance warning, Halassa says. However, mice with the ptchd1 mutation were unable to use these cues to improve their performance, even when their TRN deficit was treated with EBIO.

This suggested that another brain circuit must be playing a role in the animals’ ability to filter out distracting noise. To test the possibility that this circuit is located in the prefrontal cortex, the researchers recorded from neurons in that region while mice lacking ptch1 performed the task. They found that neuronal activity died out much faster in these mice than in the prefrontal cortex of normal mice. That led the researchers to test another drug, known as modafinil, which is FDA-approved to treat narcolepsy and is sometimes prescribed to improve memory and attention.

The researchers found that when they treated mice missing ptchd1 with both modafinil and EBIO, their hypersensitivity disappeared, and their performance on the task was the same as that of normal mice.

Targeting circuits

This successful reversal of symptoms suggests that the mice missing ptchd1 experience a combination of circuit deficits that each contribute differently to noise hypersensitivity. One circuit filters noise, while the other helps to control noise filtering based on external cues. Ptch1 mutations affect both circuits, in different ways that can be treated with different drugs.

Both of those circuits could also be affected by other genetic mutations that have been linked to autism and other neurological disorders, Halassa says. Targeting those circuits, rather than specific genetic mutations, may offer a more effective way to treat such disorders, he says.

“These circuits are important for moving things around the brain — sensory information, cognitive information, working memory,” he says. “We’re trying to reverse-engineer circuit operations in the service of figuring out what to do about a real human disease.”

He now plans to study circuit-level disturbances that arise in schizophrenia. That disorder affects circuits involving cognitive processes such as inference — the ability to draw conclusions from available information.

The research was funded by the Simons Center for the Social Brain at MIT, the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, the Pew Foundation, the Human Frontiers Science Program, the National Institutes of Health, the James and Patricia Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowship, and a National Alliance for the Research of Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award.