When it comes to brain function, neurons get a lot of the glory. But healthy brains depend on the cooperation of many kinds of cells. The most abundant of the brain’s non-neuronal cells are astrocytes, star-shaped cells with a lot of responsibilities. Astrocytes help shape neural circuits, participate in information processing, and provide nutrient and metabolic support to neurons. Individual cells can take on new roles throughout their lifetimes, and at any given time, the astrocytes in one part of the brain will look and behave differently than the astrocytes somewhere else.

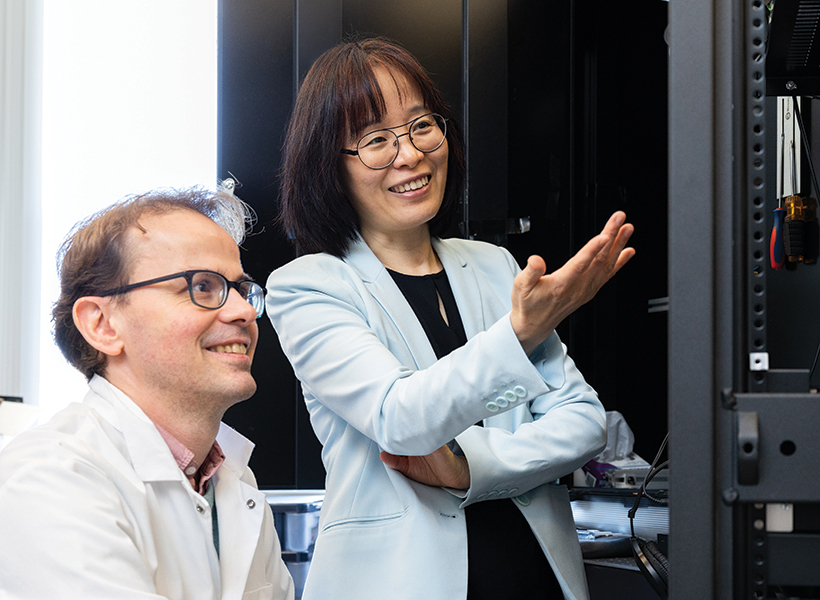

After an extensive analysis by scientists at MIT’s McGovern Institute, neuroscientists now have an atlas detailing astrocytes’ dynamic diversity. Its maps depict the regional specialization of astrocytes across the brains of both mice and marmosets—two powerful models for neuroscience research—and show how their populations shift as brains develop, mature, and age. The study, reported in the November 20 issue of the journal Neuron, was led by Guoping Feng, the James W. (1963) and Patricia T. Poitras Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. This work was supported by the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research, part of the Yang Tan Collective at MIT, and the National Institutes of Health’s BRAIN Initiative.

Probing the unknown

“It’s really important for us to pay attention to non-neuronal cells’ role in health and disease,” says Feng, who is also the associate director of the McGovern Institute, the director of the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research at MIT, and a member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. And indeed, these cells—once seen as merely supporting players—have gained more of the spotlight in recent years. Astrocytes are known to play vital roles in the brain’s development and function, and their dysfunction seems to contribute to many psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. “But compared to neurons, we know a lot less—especially during development,” Feng adds.

Feng and Margaret Schroeder, a former graduate student in his lab, thought it was important to understand astrocyte diversity across three axes: space, time, and species. They knew from earlier work in the lab, done in collaboration with Steve McCarroll’s lab at Harvard and led by Fenna Krienen in his group, that in adult animals, different parts of the brain have distinctive sets of astrocytes.

“The natural question was, how early in development do we think this regional patterning of astrocytes starts?” Schroeder says.

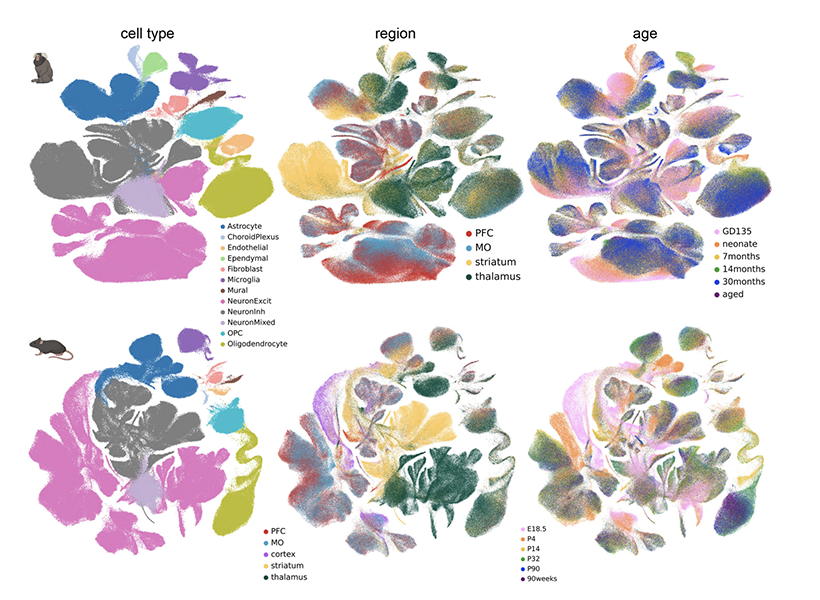

To find out, she and her colleagues collected brain cells from mice and marmosets at six stages of life, spanning embryonic development to old age. For each animal, they sampled cells from four different brain regions: the prefrontal cortex, the motor cortex, the striatum, and the thalamus.

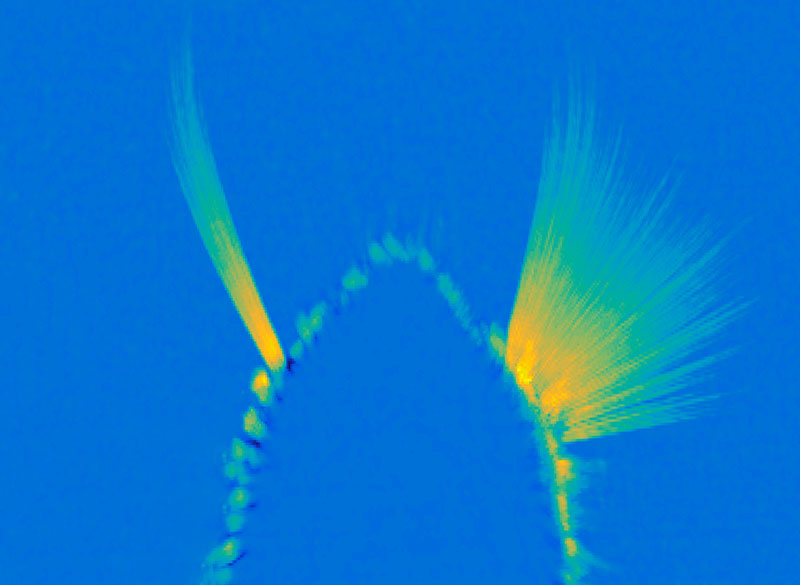

Then, working with Krienen, who is now an assistant professor at Princeton University, they analyzed the molecular contents of those cells, creating a profile of genetic activity for each one. That profile was based on the mRNA copies of genes found inside the cell, which are known collectively as the cell’s transcriptome. Determining which genes a cell is using and how active those genes are gives researchers insight into a cell’s function and is one way of defining its identity.

Dynamic diversity

After assessing the transcriptomes of about 1.4 million brain cells, the group focused in on the astrocytes, analyzing and comparing their patterns of gene expression. At every life stage, from before birth to old age, the team found regional specialization: Astrocytes from different brain regions had similar patterns of gene expression, which were distinct from those of astrocytes in other brain regions.

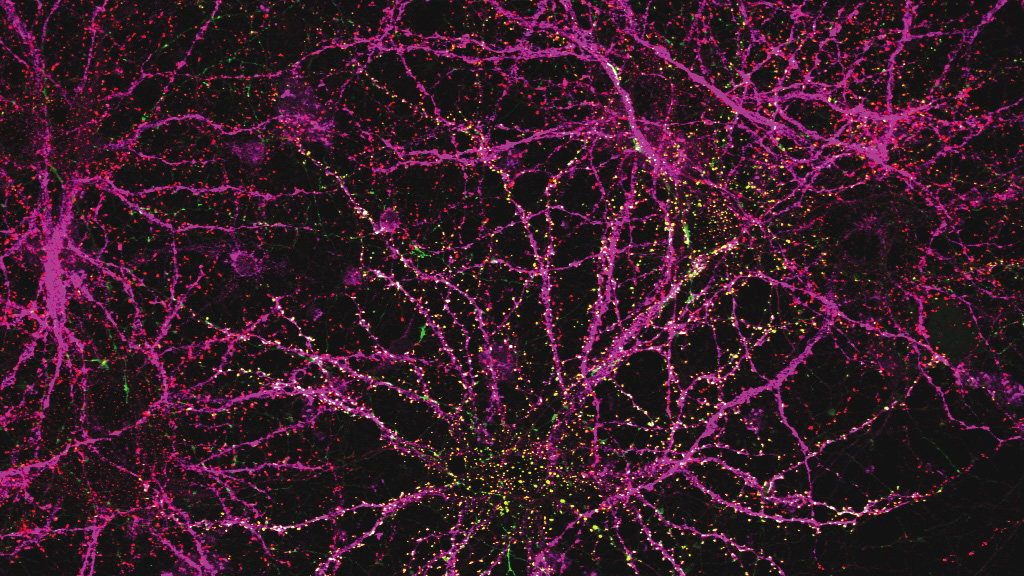

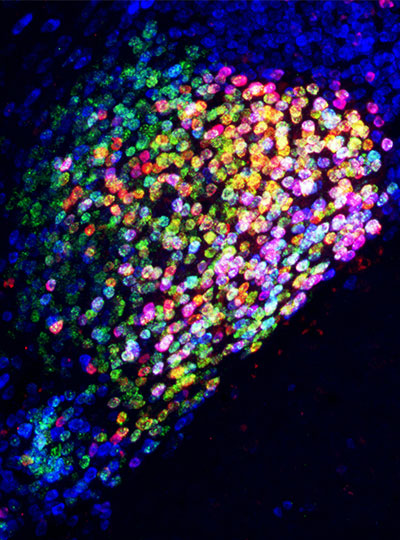

This regional specialization was also apparent in the distinct shapes of astrocytes in different parts of the brain, which the team was able to see with expansion microscopy, a high-resolution imaging method developed by McGovern colleague Edward Boyden that reveals fine cellular features.

Notably, the astrocytes in each region changed as animals matured. “When we looked at our late embryonic time point, the astrocytes were already regionally patterned. But when we compare that to the adult profiles, they had completely shifted again,” Schroeder says. “So there’s something happening over postnatal development.” The most dramatic changes the team detected occurred between birth and early adolescence, a period during which brains rapidly rewire as animals begin to interact with the world and learn from their experiences.

Feng and Schroeder suspect that the changes they observed may be driven by the neural circuits that are sculpted and refined as the brain matures. “What we think they’re doing is kind of adapting to their local neuronal niche,” Schroeder says. “The types of genes that they are upregulating and changing during development points to their interaction with neurons.” Feng adds that astrocytes may change their genetic programs in response to nearby neurons, or alternatively, they might help direct the development or function of local circuits as they adopt identities best suited to support particular neurons.

Both mouse and marmoset brains exhibited regional specialization of astrocytes and changes in those populations over time. But when the researchers looked at the specific genes whose activity defined various astrocyte populations, the data from the two species diverged. Schroeder calls this a note of caution for scientists who study astrocytes in animal models, and adds that the new atlas will help researchers assess the potential relevance of findings across species.

Beyond astrocytes

With a new understanding of astrocyte diversity, Feng says his team will pay close attention to how these cells are impacted by the disease-related genes they study and how those effects change during development. He also notes that the gene expression data in the atlas can be used to predict interactions between astrocytes and neurons. “This will really guide future experiments: how these cells’ interactions can shift with changes in the neurons or changes in the astrocytes,” he says.

The Feng lab is eager for other researchers to take advantage of the massive amounts of data they generated as they produced their atlas. Schroeder points out that the team analyzed the transcriptomes of all kinds of cells in the brain regions they studied, not just astrocytes. They are sharing their findings so researchers can use them to understand when and where specific genes are used in the brain, or dig in more deeply to further to explore the brain’s cellular diversity.