Now, neuroscientists at MIT’s McGovern Institute have homed in on key brain circuits that help guide decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. By studying how mice interpret ambiguous sensory cues, they’ve found neurons that stop the brain from using unreliable information.

“One area cares about the content of the message—that’s the prefrontal cortex—and the thalamus seems to care about how certain the input is.” – Michael Halassa

The findings, published October 6, 2021, in the journal Nature, could help researchers develop treatments for schizophrenia and related conditions, whose symptoms may be at least partly due to affected individuals’ inability to effectively gauge uncertainty.

Decoding ambiguity

“A lot of cognition is really about handling different types of uncertainty,” says McGovern Associate Investigator Michael Halassa, explaining that we all must use ambiguous information to make inferences about what’s happening in the world. Part of dealing with this ambiguity involves recognizing how confident we can be in our conclusions. And when this process fails, it can dramatically skew our interpretation of the world around us.

“In my mind, schizophrenia spectrum disorders are really disorders of appropriately inferring the causes of events in the world and what other people think,” says Halassa, who is a practicing psychiatrist. Patients with these disorders often develop strong beliefs based on events or signals most people would dismiss as meaningless or irrelevant, he says. They may assume hidden messages are embedded in a garbled audio recording, or worry that laughing strangers are plotting against them. Such things are not impossible—but delusions arise when patients fail to recognize that they are highly unlikely.

Halassa and postdoctoral researcher Arghya Mukherjee wanted to know how healthy brains handle uncertainty, and recent research from other labs provided some clues. Functional brain imaging had shown that when people are asked to study a scene but they aren’t sure what to pay attention to, a part of the brain called the mediodorsal thalamus becomes active. The less guidance people are given for this task, the harder the mediodorsal thalamus works.

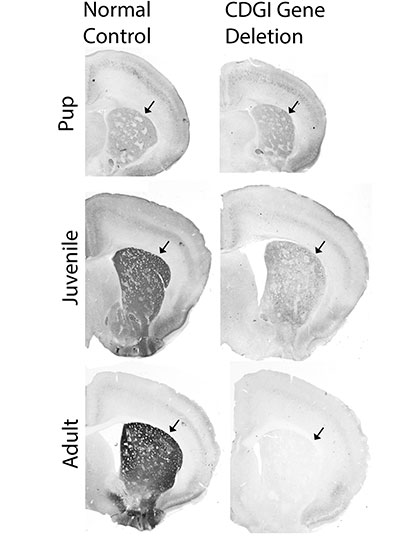

The thalamus is a sort of crossroads within the brain, made up of cells that connect distant brain regions to one another. Its mediodorsal region sends signals to the prefrontal cortex, where sensory information is integrated with our goals, desires, and knowledge to guide behavior. Previous work in the Halassa lab showed that the mediodorsal thalamus helps the prefrontal cortex tune in to the right signals during decision-making, adjusting signaling as needed when circumstances change. Intriguingly, this brain region has been found to be less active in people with schizophrenia than it is in others.

Working with postdoctoral researcher Norman Lam and research scientist Ralf Wimmer, Halassa and Mukherjee designed a set of animal experiments to examine the mediodorsal thalamus’s role in handling uncertainty. Mice were trained to respond to sensory signals according to audio cues that alerted them whether to focus on either light or sound. When the animals were given conflicting cues, it was up to them animal to figure out which one was represented most prominently and act accordingly. The experimenters varied the uncertainty of this task by manipulating the numbers and ratio of the cues.

Division of labor

By manipulating and recording activity in the animals’ brains, the researchers found that the prefrontal cortex got involved every time mice completed this task, but the mediodorsal thalamus was only needed when the animals were given signals that left them uncertain how to behave. There was a simple division of labor within the brain, Halassa says. “One area cares about the content of the message—that’s the prefrontal cortex—and the thalamus seems to care about how certain the input is.”

Within the mediodorsal thalamus, Halassa and Mukherjee found a subset of cells that were especially active when the animals were presented with conflicting sound cues. These neurons, which connect directly to the prefrontal cortex, are inhibitory neurons, capable of dampening downstream signaling. So when they fire, Halassa says, they effectively stop the brain from acting on unreliable information. Cells of a different type were focused on the uncertainty that arises when signaling is sparse. “There’s a dedicated circuitry to integrate evidence across time to extract meaning out of this kind of assessment,” Mukherjee explains.

As Halassa and Mukherjee investigate these circuits more deeply, a priority will be determining whether they are disrupted in people with schizophrenia. To that end, they are now exploring the circuitry in animal models of the disorder. The hope, Mukherjee says, is to eventually target dysfunctional circuits in patients, using noninvasive, focused drug delivery methods currently under development. “We have the genetic identity of these circuits. We know they express specific types of receptors, so we can find drugs that target these receptors,” he says. “Then you can specifically release these drugs in the mediodorsal thalamus to modulate the circuits as a potential therapeutic strategy.”

This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH107680-05 and R01MH120118-02).