The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters today announced the 2024 Kavli Prize Laureates in the fields of astrophysics, nanoscience, and neuroscience. The 2024 Kavli Prize in Neuroscience honors Nancy Kanwisher, the Walter A. Rosenblith Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT and an investigator at the McGovern Institute, along with UC Berkeley neurobiologist Doris Tsao, and Rockefeller University neuroscientist Winrich Freiwald for their discovery of a highly localized and specialized system for representation of faces in human and non-human primate neocortex. The neuroscience laureates will share $1 million USD.

“Kanwisher, Freiwald, and Tsao together discovered a localized and specialized neocortical system for face recognition,” says Kristine Walhovd, Chair of the Kavli Neuroscience Committee. “Their outstanding research will ultimately further our understanding of recognition not only of faces, but objects and scenes.”

Overcoming failure

As a graduate student at MIT in the early days of functional brain imaging, Kanwisher was fascinated by the potential of the emerging technology to answer a suite of questions about the human mind. But a lack of brain imaging resources and a series of failed experiments led Kanwisher consider leaving the field for good. She credits her advisor, MIT Professor of Psychology Molly Potter, for supporting her through this challenging time and for teaching her how to make powerful inferences about the inner workings of the mind from behavioral data alone.

After receiving her PhD from MIT, Kanwisher spent a year studying nuclear strategy with a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in Peace and International Security, but eventually returned to science by accepting a faculty position at Harvard University where she could use the latest brain imaging technology to pursue the scientific questions that had always fascinated her.

Zeroing in on faces

Recognizing faces is important for social interaction in many animals. Previous work in human psychology and animal research had suggested the existence of a functionally specialized system for face recognition, but this system had not clearly been identified with brain imaging technology. It is here that Kanwisher saw her opportunity.

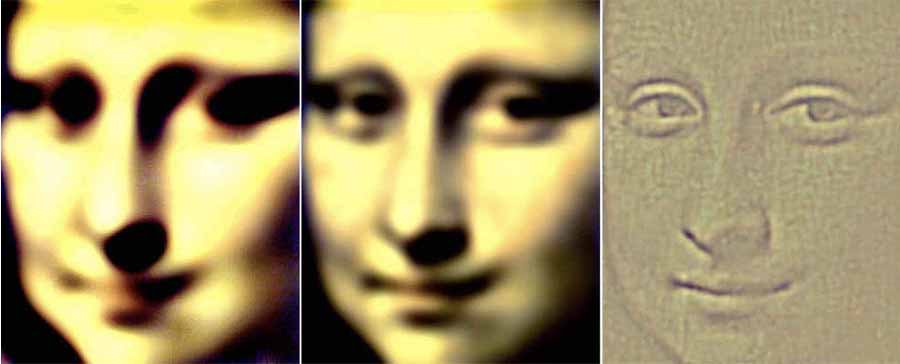

Using a new method at the time, called functional magnetic resonance imaging or fMRI, Kanwisher’s team scanned people while they looked at faces and while they looked at objects, and searched for brain regions that responded more to one than the other. They found a small patch of neocortex, now called the fusiform face area (FFA), that is dedicated specifically to the task of face recognition. She found individual differences in the location of this area and devised an analysis technique to effectively localize specialized functional regions in the brain. This technique is now widely used and applied to domains beyond the face recognition system. Notably, Kanwisher’s first FFA paper was co-authored with Josh McDermott, who was an undergrad at Harvard University at the time, and is now an associate investigator at the McGovern Institute and holds a faculty position alongside Kanwisher in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

From humans to monkeys

Inspired by Kanwisher´s findings, Winrich Freiwald and Doris Tsao together used fMRI to localize similar face patches in macaque monkeys. They mapped out six distinct brain regions, known as the face patch system, including these regions’ functional specialization and how they are connected. By recording the activity of individual brain cells, they revealed how cells in some face patches specialize in faces with particular views.

Tsao proceeded to identify how the face patches work together to identify a face, through a specific code that enables single cells to identify faces by assembling information of facial features. For example, some cells respond to the presence of hair, others to the distance between the eyes. Freiwald uncovered that a separate brain region, called the temporal pole, accelerates our recognition of familiar faces, and that some cells are selectively responsive to familiar faces.

“It was a special thrill for me when Doris and Winrich found face patches in monkeys using fMRI,” says Kanwisher, whose lab at MIT’s McGovern Institute has gone on to uncover many other regions of the human brain that engage in specific aspects of perception and cognition. “They are scientific heroes to me, and it is a thrill to receive the Kavli Prize in neuroscience jointly with them.”

“Nancy and her students have identified neocortical subregions that differentially engage in the perception of faces, places, music and even what others think,” says McGovern Institute Director Robert Desimone. “We are delighted that her groundbreaking work into the functional organization of the human brain is being honored this year with the Kavli Prize.”

Together, the laureates, with their work on neocortical specialization for face recognition, have provided basic principles of neural organization which will further our understanding of how we perceive the world around us.

About the Kavli Prize

The Kavli Prize is a partnership among The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, and The Kavli Foundation (USA). The Kavli Prize honors scientists for breakthroughs in astrophysics, nanoscience and neuroscience that transform our understanding of the big, the small and the complex. Three one-million-dollar prizes are awarded every other year in each of the three fields. The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters selects the laureates based on recommendations from three independent prize committees whose members are nominated by The Chinese Academy of Sciences, The French Academy of Sciences, The Max Planck Society of Germany, The U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and The Royal Society, UK.