The National Academy of Sciences has elected 120 members and 24 international members, including five faculty members from MIT. Guoping Feng, Piotr Indyk, Daniel J. Kleitman, Daniela Rus, and Senthil Todadri were elected in recognition of their “distinguished and continuing achievements in original research.” Membership to the National Academy of Sciences is one of the highest honors a scientist can receive in their career.

Among the new members added this year are also nine MIT alumni, including Zvi Bern ’82; Harold Hwang ’93, SM ’93; Leonard Kleinrock SM ’59, PhD ’63; Jeffrey C. Lagarias ’71, SM ’72, PhD ’74; Ann Pearson PhD ’00; Robin Pemantle PhD ’88; Jonas C. Peters PhD ’98; Lynn Talley PhD ’82; and Peter T. Wolczanski ’76. Those elected this year bring the total number of active members to 2,617, with 537 international members.

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit institution that was established under a congressional charter signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. It recognizes achievement in science by election to membership, and — with the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Medicine — provides science, engineering, and health policy advice to the federal government and other organizations.

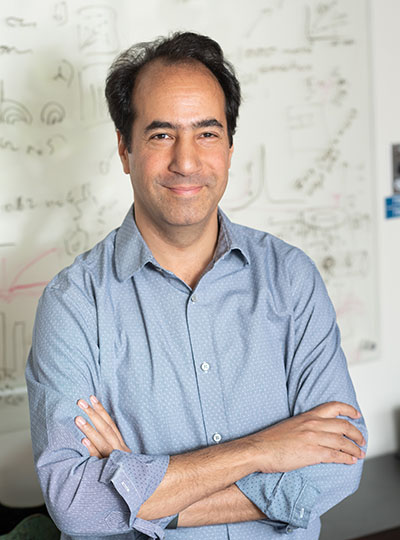

Guoping Feng

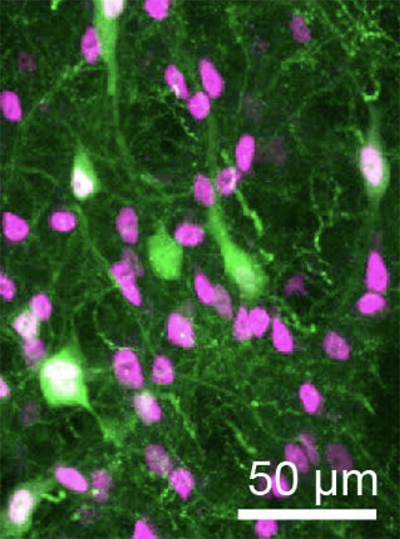

Guoping Feng is the James W. (1963) and Patricia T. Poitras Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. He is also associate director and investigator in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, a member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and director of the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research.

His research focuses on understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate the development and function of synapses, the places in the brain where neurons connect and communicate. He’s interested in how defects in the synapses can contribute to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. By understanding the fundamental mechanisms behind these disorders, he’s producing foundational knowledge that may guide the development of new treatments for conditions like obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia.

Feng received his medical training at Zhejiang University Medical School in Hangzhou, China, and his PhD in molecular genetics from the State University of New York at Buffalo. He did his postdoctoral training at Washington University at St. Louis and was on the faculty at Duke University School of Medicine before coming to MIT in 2010. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2023.

Piotr Indyk

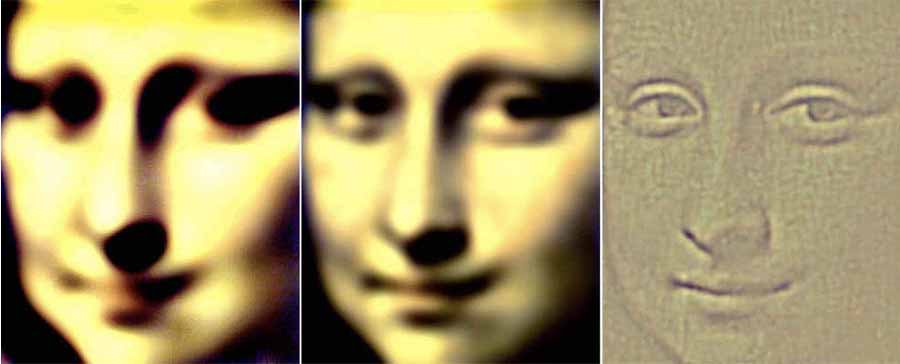

Piotr Indyk is the Thomas D. and Virginia W. Cabot Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. He received his magister degree from the University of Warsaw and his PhD from Stanford University before coming to MIT in 2000.

Indyk’s research focuses on building efficient, sublinear, and streaming algorithms. He’s developed, for example, algorithms that can use limited time and space to navigate massive data streams, that can separate signals into individual frequencies faster than other methods, and can address the “nearest neighbor” problem by finding highly similar data points without needing to scan an entire database. His work has applications on everything from machine learning to data mining.

He has been named a Simons Investigator and a fellow of the Association for Computer Machinery. In 2023, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Daniel J. Kleitman

Daniel Kleitman, a professor emeritus of applied mathematics, has been at MIT since 1966. He received his undergraduate degree from Cornell University and his master’s and PhD in physics from Harvard University before doing postdoctoral work at Harvard and the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Kleitman’s research interests include operations research, genomics, graph theory, and combinatorics, the area of math concerned with counting. He was actually a professor of physics at Brandeis University before changing his field to math, encouraged by the prolific mathematician Paul Erdős. In fact, Kleitman has the rare distinction of having an Erdős number of just one. The number is a measure of the “collaborative distance” between a mathematician and Erdős in terms of authorship of papers, and studies have shown that leading mathematicians have particularly low numbers.

He’s a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and has made important contributions to the MIT community throughout his career. He was head of the Department of Mathematics and served on a number of committees, including the Applied Mathematics Committee. He also helped create web-based technology and an online textbook for several of the department’s core undergraduate courses. He was even a math advisor for the MIT-based film “Good Will Hunting.”

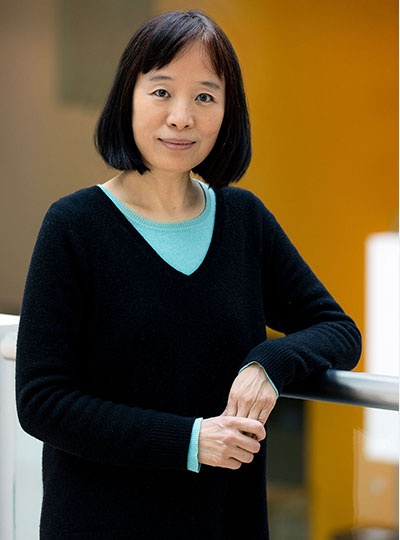

Daniela Rus

Daniela Rus, the Andrew (1956) and Erna Viterbi Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, is the director of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). She also serves as director of the Toyota-CSAIL Joint Research Center.

Her research on robotics, artificial intelligence, and data science is geared toward understanding the science and engineering of autonomy. Her ultimate goal is to create a future where machines are seamlessly integrated into daily life to support people with cognitive and physical tasks, and deployed in way that ensures they benefit humanity. She’s working to increase the ability of machines to reason, learn, and adapt to complex tasks in human-centered environments with applications for agriculture, manufacturing, medicine, construction, and other industries. She’s also interested in creating new tools for designing and fabricating robots and in improving the interfaces between robots and people, and she’s done collaborative projects at the intersection of technology and artistic performance.

Rus received her undergraduate degree from the University of Iowa and her PhD in computer science from Cornell University. She was a professor of computer science at Dartmouth College before coming to MIT in 2004. She is part of the Class of 2002 MacArthur Fellows; was elected to the National Academy of Engineering and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and is a fellow of the Association for Computer Machinery, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

Senthil Todadri

Senthil Todadri, a professor of physics, came to MIT in 2001. He received his undergraduate degree from the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur and his PhD from Yale University before working as a postdoc at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics in Santa Barbara, California.

Todadri’s research focuses on condensed matter theory. He’s interested in novel phases and phase transitions of quantum matter that expand beyond existing paradigms. Combining modeling experiments and abstract methods, he’s working to develop a theoretical framework for describing the physics of these systems. Much of that work involves understanding the phenomena that arise because of impurities or strong interactions between electrons in solids that don’t conform with conventional physical theories. He also pioneered the theory of deconfined quantum criticality, which describes a class of phase transitions, and he discovered the dualities of quantum field theories in two dimensional superconducting states, which has important applications to many problems in the field.

Todadri has been named a Simons Investigator, a Sloan Research Fellow, and a fellow of the American Physical Society. In 2023, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences