For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that the same process can be driven by mammalian cells; they believe extrusion may serve as a way for the body to eliminate cancerous or precancerous cells.

“Cell extrusion is a mechanism of cell elimination used by organisms as diverse as sponges, insects, and humans,” says H. Robert Horvitz, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology at MIT, a member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and the senior author of the study. “The discovery that extrusion is driven by a failure in DNA replication was unexpected and offers a new way to think about and possibly intervene in certain diseases, particularly cancer.”

MIT postdoc Vivek Dwivedi is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature. Other authors of the paper are King’s College London research fellow Carlos Pardo-Pastor, MIT research specialist Rita Droste, MIT postdoc Ji Na Kong, MIT graduate student Nolan Tucker, Novartis scientist and former MIT postdoc Daniel Denning, and King’s College London professor of biology Jody Rosenblatt.

Stuck in the cell cycle

In the 1980s, Horvitz was one of the first scientists to analyze a type of programmed cell suicide called apoptosis, which organisms use to eliminate cells that are no longer needed. He made his discoveries using C. elegans, a tiny nematode that contains exactly 959 cells. The developmental lineage of each cell is known, and embryonic development follows the same pattern every time. Throughout this developmental process, 1,090 cells are generated, and 131 cells undergo programmed cell suicide by apoptosis.

Horvitz’s lab later showed that if the worms were genetically mutated so that they could not eliminate cells by apoptosis, a few of those 131 cells would instead be eliminated by cell extrusion, which appears to be able to serve as a backup mechanism to apoptosis. How this extrusion process gets triggered, however, remained a mystery.

To unravel this mystery, Dwivedi performed a large-scale screen of more than 11,000 C. elegans genes. One by one, he and his colleagues knocked down the expression of each gene in worms that could not perform apoptosis. This screen allowed them to identify genes that are critical for turning on cell extrusion during development.

To the researchers’ surprise, many of the genes that turned up as necessary for extrusion were involved in the cell division cycle. These genes were primarily active during first steps of the cell cycle, which involve initiating the cell division cycle and copying the cell’s DNA.

Further experiments revealed that cells that are eventually extruded do initially enter the cell cycle and begin to replicate their DNA. However, they appear to get stuck in this phase, leading them to be extruded.

Most of the cells that end up getting extruded are unusually small, and are produced from an unequal cell division that results in one large daughter cell and one much smaller one. The researchers showed that if they interfered with the genes that control this process, so that the two daughter cells were closer to the same size, the cells that normally would have been extruded were able to successfully complete the cell cycle and were not extruded.

The researchers also showed that the failure of the very small cells to complete the cell cycle stems from a shortage of the proteins and DNA building blocks needed to copy DNA. Among other key proteins, the cells likely don’t have enough of an enzyme called LRR-1, which is critical for DNA replication. When DNA replication stalls, proteins that are responsible for detecting replication stress quickly halt cell division by inactivating a protein called CDK1. CDK1 also controls cell adhesion, so the researchers hypothesize that when CDK1 is turned off, cells lose their stickiness and detach, leading to extrusion.

Cancer protection

Horvitz’s lab then teamed up with researchers at King’s College London, led by Rosenblatt, to investigate whether the same mechanism might be used by mammalian cells. In mammals, cell extrusion plays an important role in replacing the lining of the intestines, lungs, and other organs.

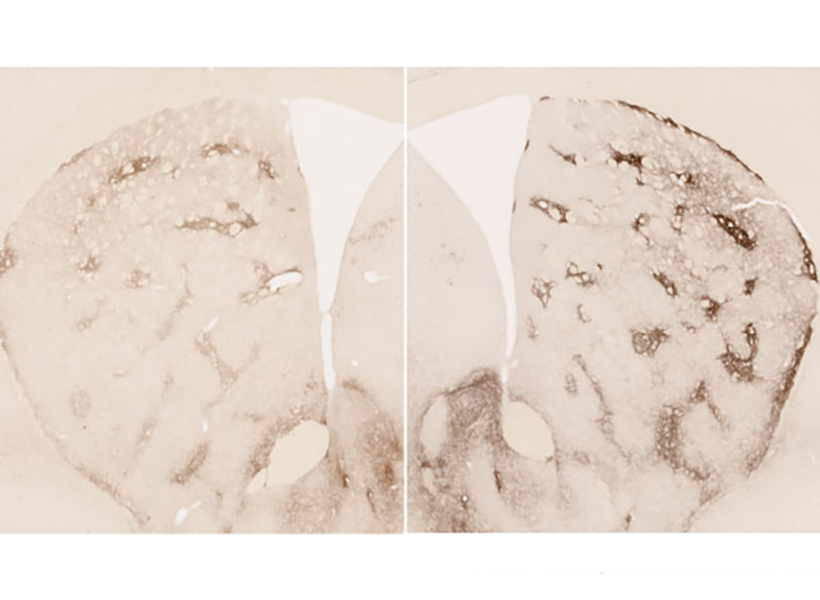

The researchers used a chemical called hydroxyurea to induce DNA replication stress in canine kidney cells grown in cell culture. The treatment quadrupled the rate of extrusion, and the researchers found that the extruded cells made it into the phase of the cell cycle where DNA is replicated before being extruded. They also showed that in mammalian cells, the well-known cancer suppressor p53 is involved in initiating extrusion of cells experiencing replication stress.

That suggests that in addition to its other cancer-protective roles, p53 may help to eliminate cancerous or precancerous cells by forcing them to extrude, Dwivedi says.

“Replication stress is one of the characteristic features of cells that are precancerous or cancerous. And what this finding suggests is that the extrusion of cells that are experiencing replication stress is potentially a tumor suppressor mechanism,” he says.

The fact that cell extrusion is seen in so many animals, from sponges to mammals, led the researchers to hypothesize that it may have evolved as a very early form of cell elimination that was later supplanted by programmed cell suicide involving apoptosis.

“This cell elimination mechanism depends only on the cell cycle,” Dwivedi says. “It doesn’t require any specialized machinery like that needed for apoptosis to eliminate these cells, so what we’ve proposed is that this could be a primordial form of cell elimination. This means it may have been one of the first ways of cell elimination to come into existence, because it depends on the same process that an organism uses to generate many more cells.”

Dwivedi, who earned his PhD at MIT, was a Khorana scholar before entering MIT for graduate school. This research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institutes of Health.

View the interactive version of this story in our

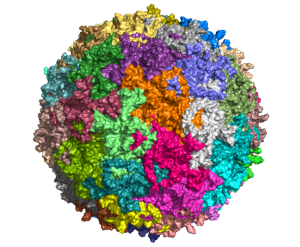

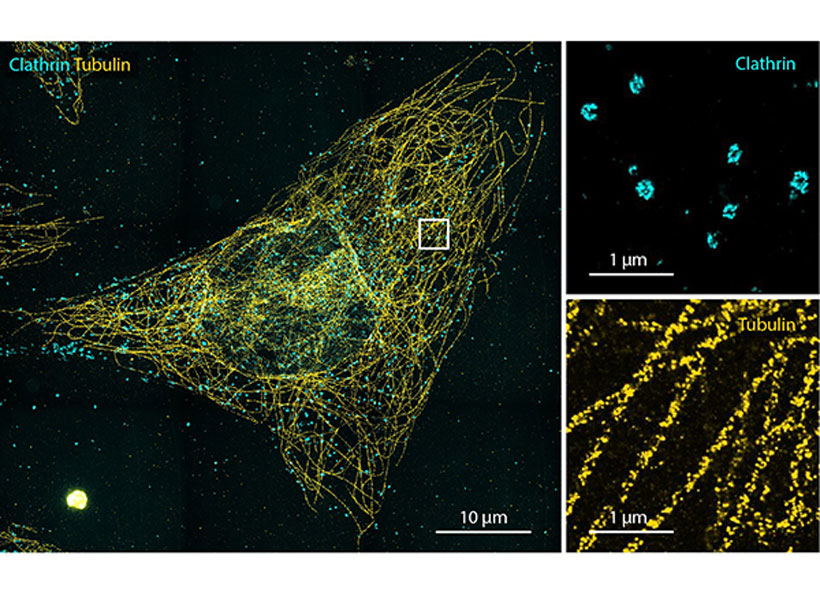

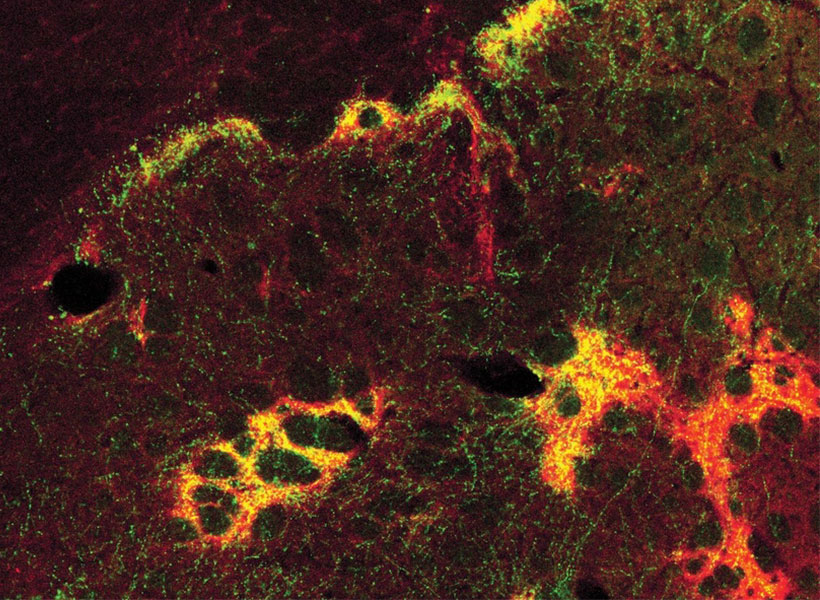

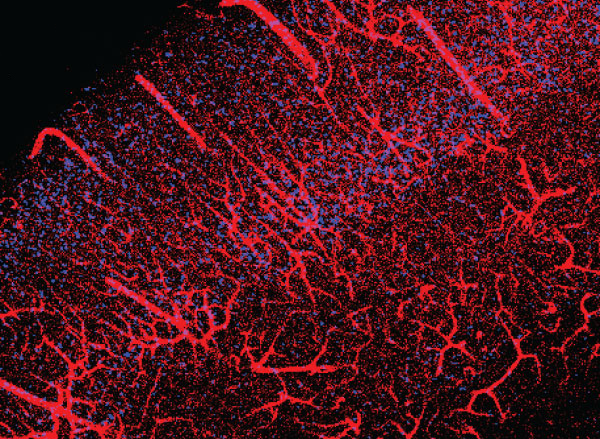

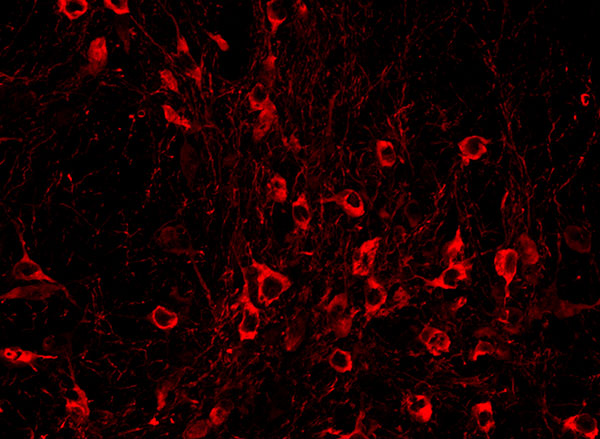

View the interactive version of this story in our  Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from.

Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from. In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret.

In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret. Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.

Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.