MIT faculty members Sabine Iatridou, Jonathan Gruber, and Rebecca Saxe are among 175 scientists, artists, and scholars awarded 2020 fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Appointed on the basis of prior achievement and exceptional promise, the 2020 Guggenheim Fellows were selected from almost 3,000 applicants.

“It’s exceptionally encouraging to be able to share such positive news at this terribly challenging time” says Edward Hirsch, president of the foundation. “A Guggenheim Fellowship has always offered practical assistance, helping fellows do their work, but for many of the new fellows, it may be a lifeline at a time of hardship, a survival tool as well as a creative one.”

Since 1925, the foundation has granted more the $375 million in fellowships to over 18,000 individuals, including Nobel laureates, Fields medalists, poets laureate, and winners of the Pulitzer Prize, among other internationally recognized honors. This year’s MIT recipients include a linguist, an economist, and a cognitive neuroscientist.

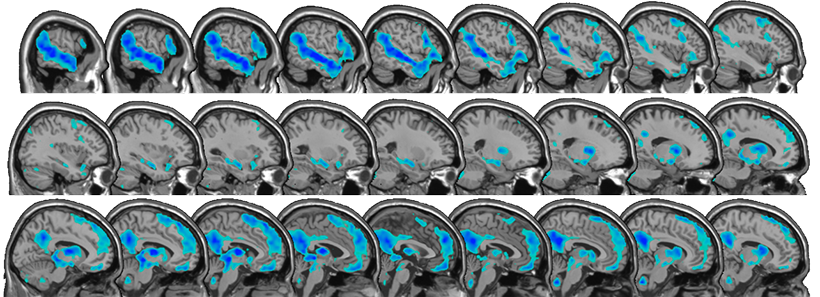

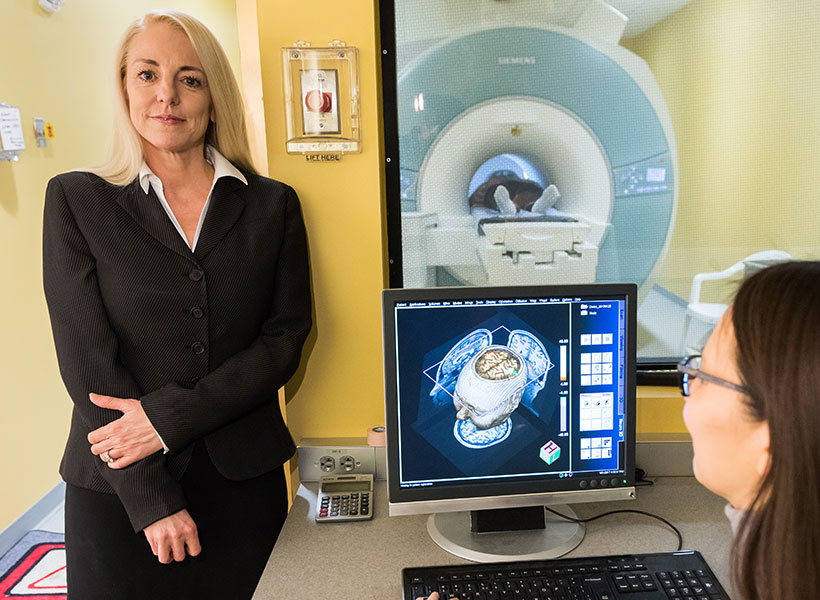

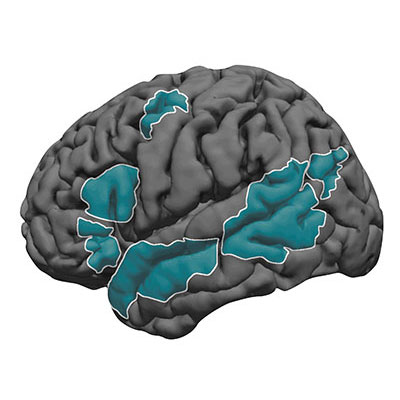

Rebecca Saxe is an associate investigator of the McGovern Institute and the John W. Jarve (1978) Professor in Brain and Cognitive Sciences. She studies human social cognition, using a combination of behavioral testing and brain imaging technologies. She is best known for her work on brain regions specialized for abstract concepts such as “theory of mind” tasks that involve understanding the mental states of other people. She also studies the development of the human brain during early infancy. She obtained her PhD from MIT and was a Harvard University junior fellow before joining the MIT faculty in 2006. Saxe was chosen in 2012 as a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum, and she received the 2014 Troland Award from the National Academy of Sciences. Her TED Talk, “How we read each other’s minds” has been viewed over 3 million times.

Jonathan Gruber is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT, the director of the Health Care Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and the former president of the American Society of Health Economists. He has published more than 175 research articles, has edited six research volumes, and is the author of “Public Finance and Public Policy,” a leading undergraduate text; “Health Care Reform,” a graphic novel; and “Jump-Starting America: How Breakthrough Science Can Revive Economic Growth and the American Dream.” In 2006 he received the American Society of Health Economists Inaugural Medal for the best health economist in the nation aged 40 and under. He served as deputy sssistant secretary for economic policy at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. He was a key architect of Massachusetts’ ambitious health reform effort, and became an inaugural member of the Health Connector Board, the main implementing body for that effort. He served as a technical consultant to the Obama administration and worked with both the administration and Congress to help craft the Affordable Care Act. In 2011, he was named “One of the Top 25 Most Innovative and Practical Thinkers of Our Time” by Slate magazine.

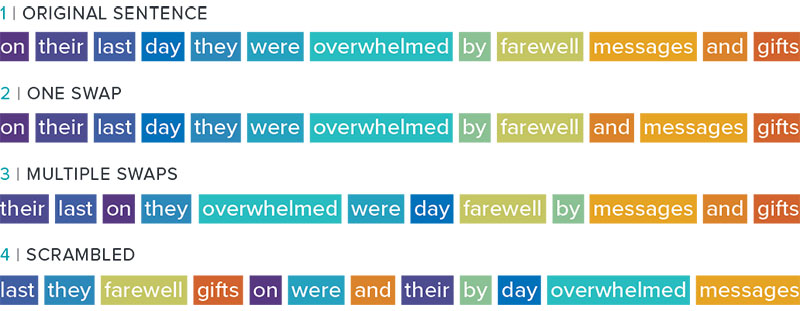

Sabine Iatridou is professor of linguistics in MIT’s Department of Linguistics and Philosophy. Her work focuses on syntax and the syntax-semantics interface, as well as comparative linguistics. She is the author and coauthor of a series of innovative papers about tense and modality that opened up whole new domains of research for the field. Since those publications, she has made foundational contributions to many branches of linguistics that connect form with meaning. She is the recipient of the National Young Investigator Award (USA), of an honorary doctorate from the University of Crete in Greece, and of an award from the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences. She was elected fellow of the Linguistic Society of America. She is co-founder and co-director of the CreteLing Summer School of Linguistics.

“As we grapple with the difficulties of the moment, it is also important to look to the future,” says Hirsch. “The artists, writers, scholars, and scientific researchers supported by the fellowship will help us understand and learn from what we are enduring individually and collectively, and it is an honor for the foundation to help them do their essential work.”