As part of our Ask the Brain series, Anila D’Mello, a postdoctoral fellow in John Gabrieli’s lab answers the question,”What is the social brain?”

_____

“Knock Knock.”

“Who’s there?”

“The Social Brain.”

“The Social Brain, who?”

Call and response jokes, like the “Knock Knock” joke above, leverage our common understanding of how a social interaction typically proceeds. Joke telling allows us to interact socially with others based on our shared experiences and understanding of the world. But where do these abilities “live” in the brain and how does the social brain develop?

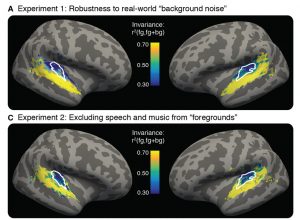

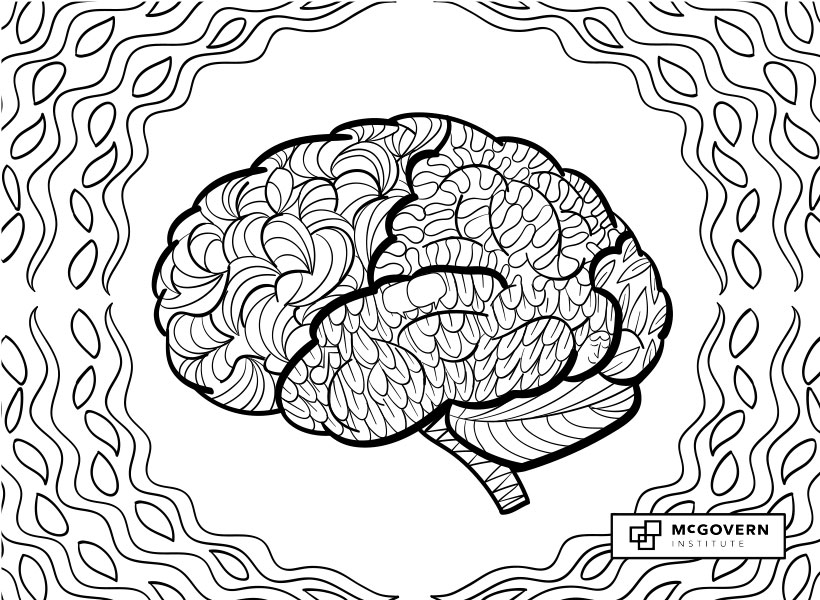

Neuroimaging and lesion studies have identified a network of brain regions that support social interaction, including the ability to understand and partake in jokes – we refer to this as the “social brain.” This social brain network is made up of multiple regions throughout the brain that together support complex social interactions. Within this network, each region likely contributes to a specific type of social processing. The right temporo-parietal junction, for instance, is important for thinking about another person’s mental state, whereas the amygdala is important for the interpretation of emotional facial expressions and fear processing. Damage to these brain regions can have striking effects on social behaviors. One recent study even found that individuals with bigger amygdala volumes had larger and more complex social networks!

Though social interaction is such a fundamental human trait, we aren’t born with a prewired social brain.

Much of our social ability is grown and honed over time through repeated social interactions. Brain networks that support social interaction continue to specialize into adulthood. Neuroimaging work suggests that though newborn infants may have all the right brain parts to support social interaction, these regions may not yet be specialized or connected in the right way. This means that early experiences and environments can have large influences on the social brain. For instance, social neglect, especially very early in development, can have negative impacts on social behaviors and on how the social brain is wired. One prominent example is that of children raised in orphanages or institutions, who are sometimes faced with limited adult interaction or access to language. Children raised in these conditions are more likely to have social challenges including difficulties forming attachments. Prolonged lack of social stimulation also alters the social brain in these children resulting in changes in amygdala size and connections between social brain regions.

The social brain is not just a result of our environment. Genetics and biology also contribute to the social brain in ways we don’t yet fully understand. For example, individuals with autism / autistic individuals may experience difficulties with social interaction and communication. This may include challenges with things like understanding the punchline of a joke. These challenges in autism have led to the hypothesis that there may be differences in the social brain network in autism. However, despite documented behavioral differences in social tasks, there is conflicting brain imaging evidence for whether differences exist between people with and without autism in the social brain network.

Examples such as that of autism imply that the reality of the social brain is probably much more complex than the story painted here. It is likely that social interaction calls upon many different parts of the brain, even beyond those that we have termed the “social brain,” that must work in concert to support this highly complex set of behaviors. These include regions of the brain important for listening, seeing, speaking, and moving. In addition, it’s important to remember that the social brain and regions that make it up do not stand alone. Regions of the social brain also play an intimate role in language, humor, and other cognitive processes.

“Knock Knock”

“Who’s there?”

“The Social Brain”

“The Social Brain, who?”

“I just told you…didn’t you read what I wrote?”

Anila D’Mello earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology from Georgetown University in 2012, and went on to receive her PhD in Behavior, Cognition, and Neuroscience from American University in 2017. She joined the Gabrieli lab as a postdoc in 2017 and studies the neural correlates of social communication in autism.

_____

Do you have a question for The Brain? Ask it here.

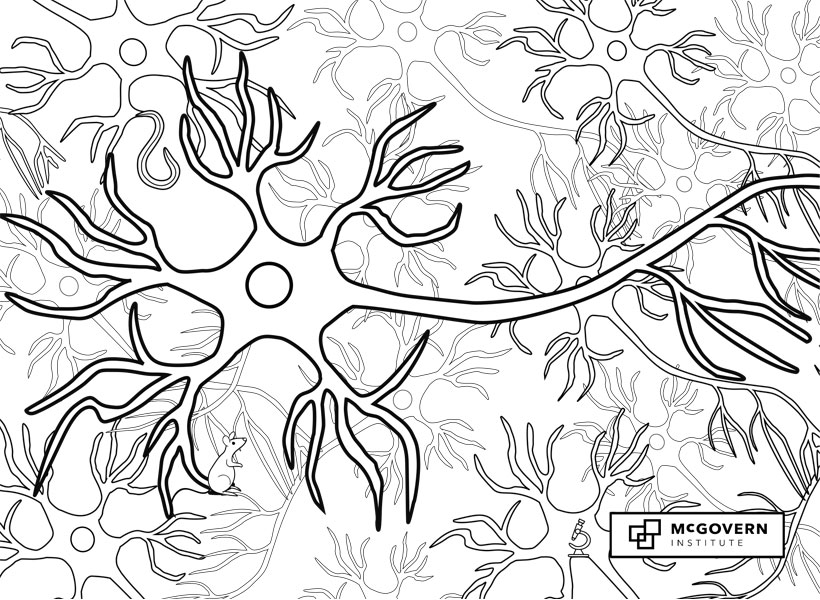

Signals flow through the nervous system from one neuron to the next across synapses.

Signals flow through the nervous system from one neuron to the next across synapses. The axon is the long, thin neural cable that carries electrical impulses called action potentials from the soma to synaptic terminals at downstream neurons.

The axon is the long, thin neural cable that carries electrical impulses called action potentials from the soma to synaptic terminals at downstream neurons. The soma, or cell body, is the control center of the neuron, where the nucleus is located.

The soma, or cell body, is the control center of the neuron, where the nucleus is located. Long branching neuronal processes called dendrites receive synaptic inputs from thousands of other neurons and carry those signals to the cell body.

Long branching neuronal processes called dendrites receive synaptic inputs from thousands of other neurons and carry those signals to the cell body.