The inextricable link between our brains and our bodies has been gaining increasing recognition among researchers and clinicians over recent years. Studies have shown that the brain-body pathway is bidirectional — meaning that our mental state can influence our physical health and vice versa. But exactly how the two interact is less clear.

A new research center at MIT, funded by a $38 million gift to the McGovern Institute for Brain Research from philanthropist K. Lisa Yang, aims to unlock this mystery by creating and applying novel tools to explore the multidirectional, multilevel interplay between the brain and other body organ systems. This gift expands Yang’s exceptional philanthropic support of human health and basic science research at MIT over the past five years.

“Lisa Yang’s visionary gift enables MIT scientists and engineers to pioneer revolutionary technologies and undertake rigorous investigations into the brain’s complex relationship with other organ systems,” says MIT President L. Rafael Reif. “Lisa’s tremendous generosity empowers MIT scientists to make pivotal breakthroughs in brain and biomedical research and, collectively, improve human health on a grand scale.”

The K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center will be directed by Polina Anikeeva, professor of materials science and engineering and brain and cognitive sciences at MIT and an associate investigator at the McGovern Institute. The center will harness the power of MIT’s collaborative, interdisciplinary life sciences research and engineering community to focus on complex conditions and diseases affecting both the body and brain, with a goal of unearthing knowledge of biological mechanisms that will lead to promising therapeutic options.

“Under Professor Anikeeva’s brilliant leadership, this wellspring of resources will encourage the very best work of MIT faculty, graduate fellows, and research — and ultimately make a real impact on the lives of many,” Reif adds.

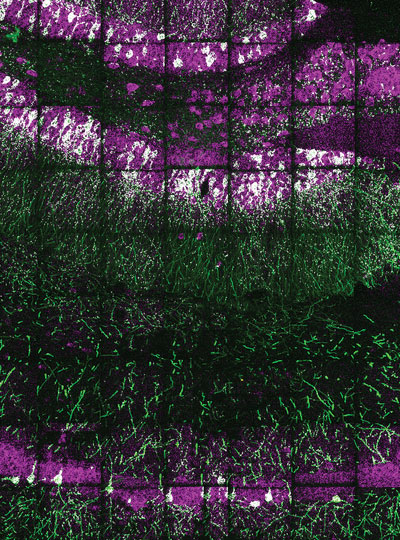

Image: Polina Anikeeva, Marie Manthey, Kareena Villalobos

Center goals

Initial projects in the center will focus on four major lines of research:

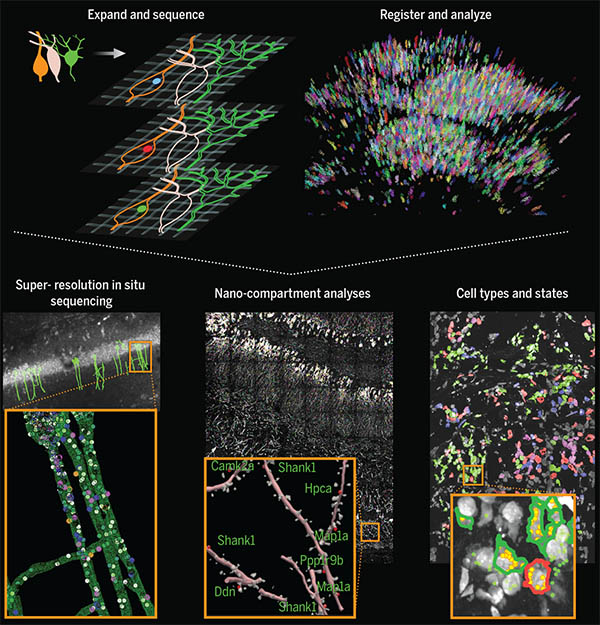

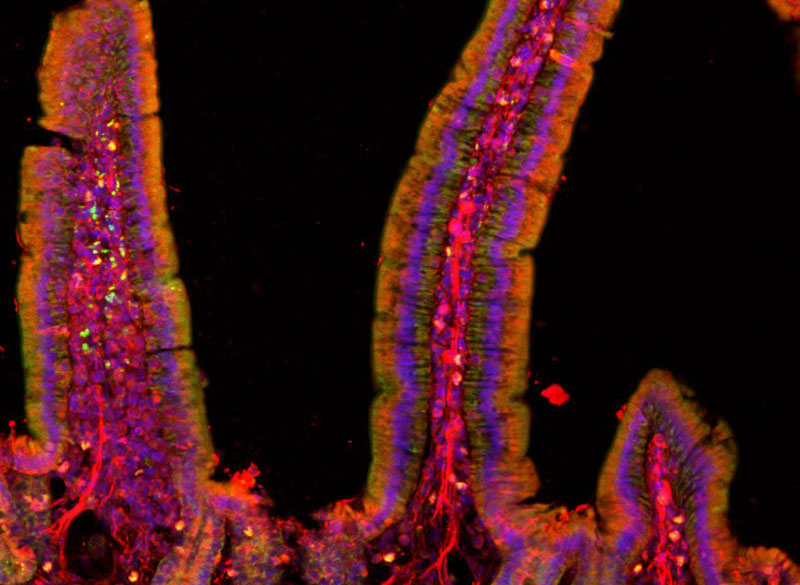

- Gut-Brain: Anikeeva’s group will expand a toolbox of new technologies and apply these tools to examine major neurobiological questions about gut-brain pathways and connections in the context of autism spectrum disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and affective disorders.

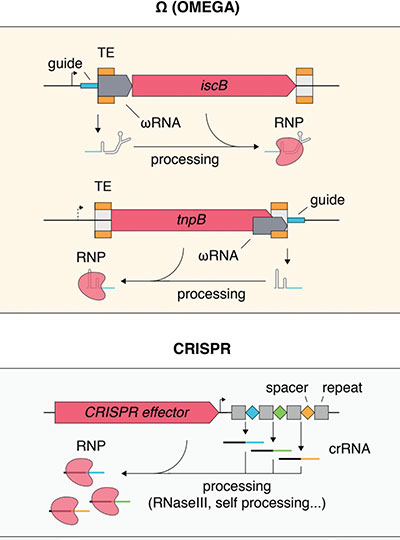

- Aging: CRISPR pioneer Feng Zhang, the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and investigator at the McGovern Institute, will lead a group in developing molecular tools for precision epigenomic editing and erasing accumulated “errors” of time, injury, or disease in various types of cells and tissues.

- Pain: The lab of Fan Wang, investigator at the McGovern Institute and professor of brain and cognitive sciences, will design new tools and imaging methods to study autonomic responses, sympathetic-parasympathetic system balance, and brain-autonomic nervous system interactions, including how pain influences these interactions.

- Acupuncture: Wang will also collaborate with Hilda (“Scooter”) Holcombe, a veterinarian in MIT’s Division of Comparative Medicine, to advance techniques for documenting changes in brain and peripheral tissues induced by acupuncture in mouse models. If successful, these techniques could lay the groundwork for deeper understandings of the mechanisms of acupuncture, specifically how the treatment stimulates the nervous system and restores function.

A key component of the K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center will be a focus on educating and training the brightest young minds who aspire to make true breakthroughs for individuals living with complex and often devastating diseases. A portion of center funding will endow the new K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Fellows Program, which will support four annual fellowships for MIT graduate students and postdocs working to advance understanding of conditions that affect both the body and brain.

Mens sana in corpore sano

“A phrase I remember reading in secondary school has always stuck with me: ‘mens sana in corpore sano’ — ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body,’” says Lisa Yang, a former investment banker committed to advocacy for individuals with visible and invisible disabilities. “When we look at how stress, nutrition, pain, immunity, and other complex factors impact our health, we truly see how inextricably linked our brains and bodies are. I am eager to help MIT scientists and engineers decode these links and make real headway in creating therapeutic strategies that result in longer, healthier lives.”

“This center marks a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for labs like mine to conduct bold and risky studies into the complexities of brain-body connections,” says Anikeeva, who works at the intersection of materials science, electronics, and neurobiology. “The K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center will offer a pathbreaking, holistic approach that bridges multiple fields of study. I have no doubt that the center will result in revolutionary strides in our understanding of the inextricable bonds between the brain and the body’s peripheral organ systems, and a bold new way of thinking in how we approach human health overall.”