In a new study, MIT researchers have discovered an additional two pathways that arise in the striatum and appear to modulate the effects of the go and no-go pathways. These newly discovered pathways connect to dopamine-producing neurons in the brain — one stimulates dopamine release and the other inhibits it.

By controlling the amount of dopamine in the brain via clusters of neurons known as striosomes, these pathways appear to modify the instructions given by the go and no-go pathways. They may be especially involved in influencing decisions that have a strong emotional component, the researchers say.

“Among all the regions of the striatum, the striosomes alone turned out to be able to project to the dopamine-containing neurons, which we think has something to do with motivation, mood, and controlling movement,” says Ann Graybiel, an MIT Institute Professor, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the new study.

Iakovos Lazaridis, a research scientist at the McGovern Institute, is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in the journal Current Biology.

New pathways

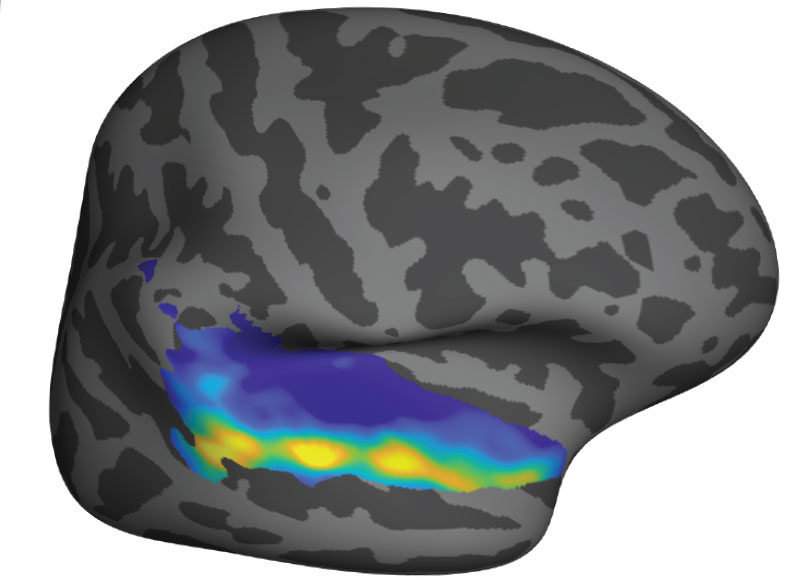

Graybiel has spent much of her career studying the striatum, a structure located deep within the brain that is involved in learning and decision-making, as well as control of movement.

Within the striatum, neurons are arranged in a labyrinth-like structure that includes striosomes, which Graybiel discovered in the 1970s. The classical go and no-go pathways arise from neurons that surround the striosomes, which are known collectively as the matrix. The matrix cells that give rise to these pathways receive input from sensory processing regions such as the visual cortex and auditory cortex. Then, they send go or no-go commands to neurons in the motor cortex.

However, the function of the striosomes, which are not part of those pathways, remained unknown. For many years, researchers in Graybiel’s lab have been trying to solve that mystery.

Their previous work revealed that striosomes receive much of their input from parts of the brain that process emotion. Within striosomes, there are two major types of neurons, classified as D1 and D2. In a 2015 study, Graybiel found that one of these cell types, D1, sends input to the substantia nigra, which is the brain’s major dopamine-producing center.

It took much longer to trace the output of the other set, D2 neurons. In the new Current Biology study, the researchers discovered that those neurons also eventually project to the substantia nigra, but first they connect to a set of neurons in the globus palladus, which inhibits dopamine output. This pathway, an indirect connection to the substantia nigra, reduces the brain’s dopamine output and inhibits movement.

The researchers also confirmed their earlier finding that the pathway arising from D1 striosomes connects directly to the substantia nigra, stimulating dopamine release and initiating movement.

“In the striosomes, we’ve found what is probably a mimic of the classical go/no-go pathways,” Graybiel says. “They’re like classic motor go/no-go pathways, but they don’t go to the motor output neurons of the basal ganglia. Instead, they go to the dopamine cells, which are so important to movement and motivation.”

Emotional decisions

The findings suggest that the classical model of how the striatum controls movement needs to be modified to include the role of these newly identified pathways. The researchers now hope to test their hypothesis that input related to motivation and emotion, which enters the striosomes from the cortex and the limbic system, influences dopamine levels in a way that can encourage or discourage action.

That dopamine release may be especially relevant for actions that induce anxiety or stress. In their 2015 study, Graybiel’s lab found that striosomes play a key role in making decisions that provoke high levels of anxiety; in particular, those that are high risk but may also have a big payoff.

“Ann Graybiel and colleagues have earlier found that the striosome is concerned with inhibiting dopamine neurons. Now they show unexpectedly that another type of striosomal neuron exerts the opposite effect and can signal reward. The striosomes can thus both up- or down-regulate dopamine activity, a very important discovery. Clearly, the regulation of dopamine activity is critical in our everyday life with regard to both movements and mood, to which the striosomes contribute,” says Sten Grillner, a professor of neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, who was not involved in the research.

Another possibility the researchers plan to explore is whether striosomes and matrix cells are arranged in modules that affect motor control of specific parts of the body.

“The next step is trying to isolate some of these modules, and by simultaneously working with cells that belong to the same module, whether they are in the matrix or striosomes, try to pinpoint how the striosomes modulate the underlying function of each of these modules,” Lazaridis says.

They also hope to explore how the striosomal circuits, which project to the same region of the brain that is ravaged by Parkinson’s disease, may influence that disorder.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Saks-Kavanaugh Foundation, the William N. and Bernice E. Bumpus Foundation, Jim and Joan Schattinger, the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research, Robert Buxton, the Simons Foundation, the CHDI Foundation, and an Ellen Schapiro and Gerald Axelbaum Investigator BBRF Young Investigator Grant.