As a cucumber plant grows, it sprouts tightly coiled tendrils that seek out supports in order to pull the plant upward. This ensures the plant receives as much sunlight exposure as possible. Now, researchers at MIT have found a way to imitate this coiling-and-pulling mechanism to produce contracting fibers that could be used as artificial muscles for robots, prosthetic limbs, or other mechanical and biomedical applications.

While many different approaches have been used for creating artificial muscles, including hydraulic systems, servo motors, shape-memory metals, and polymers that respond to stimuli, they all have limitations, including high weight or slow response times. The new fiber-based system, by contrast, is extremely lightweight and can respond very quickly, the researchers say. The findings are being reported today in the journal Science.

The new fibers were developed by MIT postdoc Mehmet Kanik and MIT graduate student Sirma Örgüç, working with professors Polina Anikeeva, Yoel Fink, Anantha Chandrakasan, and C. Cem Taşan, and five others, using a fiber-drawing technique to combine two dissimilar polymers into a single strand of fiber.

The key to the process is mating together two materials that have very different thermal expansion coefficients — meaning they have different rates of expansion when they are heated. This is the same principle used in many thermostats, for example, using a bimetallic strip as a way of measuring temperature. As the joined material heats up, the side that wants to expand faster is held back by the other material. As a result, the bonded material curls up, bending toward the side that is expanding more slowly.

Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

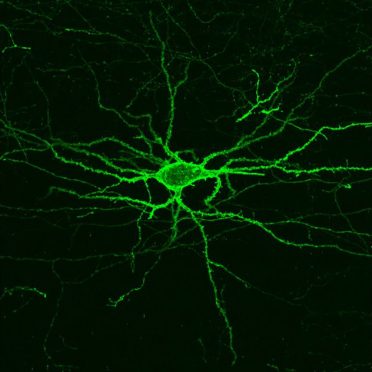

Using two different polymers bonded together, a very stretchable cyclic copolymer elastomer and a much stiffer thermoplastic polyethylene, Kanik, Örgüç and colleagues produced a fiber that, when stretched out to several times its original length, naturally forms itself into a tight coil, very similar to the tendrils that cucumbers produce. But what happened next actually came as a surprise when the researchers first experienced it. “There was a lot of serendipity in this,” Anikeeva recalls.

As soon as Kanik picked up the coiled fiber for the first time, the warmth of his hand alone caused the fiber to curl up more tightly. Following up on that observation, he found that even a small increase in temperature could make the coil tighten up, producing a surprisingly strong pulling force. Then, as soon as the temperature went back down, the fiber returned to its original length. In later testing, the team showed that this process of contracting and expanding could be repeated 10,000 times “and it was still going strong,” Anikeeva says.

Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

One of the reasons for that longevity, she says, is that “everything is operating under very moderate conditions,” including low activation temperatures. Just a 1-degree Celsius increase can be enough to start the fiber contraction.

The fibers can span a wide range of sizes, from a few micrometers (millionths of a meter) to a few millimeters (thousandths of a meter) in width, and can easily be manufactured in batches up to hundreds of meters long. Tests have shown that a single fiber is capable of lifting loads of up to 650 times its own weight. For these experiments on individual fibers, Örgüç and Kanik have developed dedicated, miniaturized testing setups.

Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

The degree of tightening that occurs when the fiber is heated can be “programmed” by determining how much of an initial stretch to give the fiber. This allows the material to be tuned to exactly the amount of force needed and the amount of temperature change needed to trigger that force.

The fibers are made using a fiber-drawing system, which makes it possible to incorporate other components into the fiber itself. Fiber drawing is done by creating an oversized version of the material, called a preform, which is then heated to a specific temperature at which the material becomes viscous. It can then be pulled, much like pulling taffy, to create a fiber that retains its internal structure but is a small fraction of the width of the preform.

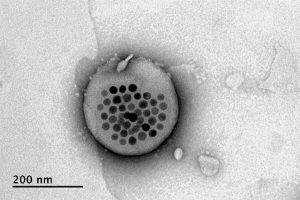

For testing purposes, the researchers coated the fibers with meshes of conductive nanowires. These meshes can be used as sensors to reveal the exact tension experienced or exerted by the fiber. In the future, these fibers could also include heating elements such as optical fibers or electrodes, providing a way of heating it internally without having to rely on any outside heat source to activate the contraction of the “muscle.”

Such fibers could find uses as actuators in robotic arms, legs, or grippers, and in prosthetic limbs, where their slight weight and fast response times could provide a significant advantage.

Some prosthetic limbs today can weigh as much as 30 pounds, with much of the weight coming from actuators, which are often pneumatic or hydraulic; lighter-weight actuators could thus make life much easier for those who use prosthetics. Such fibers might also find uses in tiny biomedical devices, such as a medical robot that works by going into an artery and then being activated,” Anikeeva suggests. “We have activation times on the order of tens of milliseconds to seconds,” depending on the dimensions, she says.

To provide greater strength for lifting heavier loads, the fibers can be bundled together, much as muscle fibers are bundled in the body. The team successfully tested bundles of 100 fibers. Through the fiber drawing process, sensors could also be incorporated in the fibers to provide feedback on conditions they encounter, such as in a prosthetic limb. Örgüç says bundled muscle fibers with a closed-loop feedback mechanism could find applications in robotic systems where automated and precise control are required.

Kanik says that the possibilities for materials of this type are virtually limitless, because almost any combination of two materials with different thermal expansion rates could work, leaving a vast realm of possible combinations to explore. He adds that this new finding was like opening a new window, only to see “a bunch of other windows” waiting to be opened.

“The strength of this work is coming from its simplicity,” he says.

The team also included MIT graduate student Georgios Varnavides, postdoc Jinwoo Kim, and undergraduate students Thomas Benavides, Dani Gonzalez, and Timothy Akintlio. The work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Science Foundation.