View the interactive version of this story in our Winter 2021 issue of Brain Scan.

View the interactive version of this story in our Winter 2021 issue of Brain Scan.

Viruses are notoriously adept invaders. The efficiency with which these unseen threats infiltrate tissues, evade immune systems, and occupy the cells of their hosts can be alarming — but it’s exactly why most McGovern neuroscientists keep a stash of viruses in the freezer.

In the hands of neuroscientists, viruses become vital tools for delivering cargo to cells.

With a bit of genetic manipulation, they can instruct neurons to produce proteins that illuminate complex circuitry, report on activity, or place certain cells under scientists’ control. They can even deliver therapies designed to correct genetic defects in patients.

“We rely on the virus to deliver whatever we want,” says McGovern Investigator Guoping Feng. “This is one of the most important technologies in neuroscience.”

Tracing connections

In Ian Wickersham’s lab, researchers are adapting a virus that, in its natural form, is devastating to the mammalian nervous system. Once it gains access to a neuron, the rabies virus spreads to connected cells, killing them within weeks. “That makes it a very dangerous pathogen, but also a very powerful tool for neuroscience,” says Wickersham, a Principal Research Scientist at the Institute.

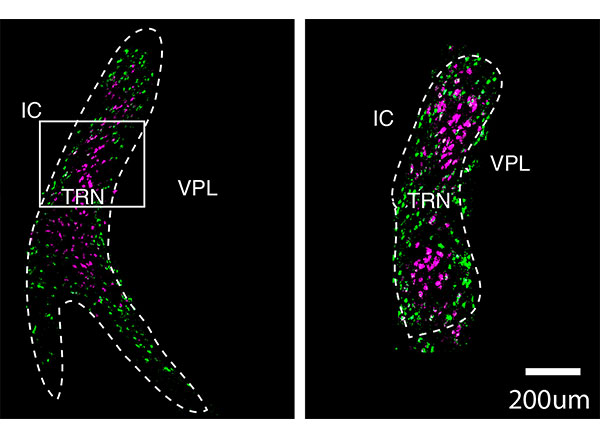

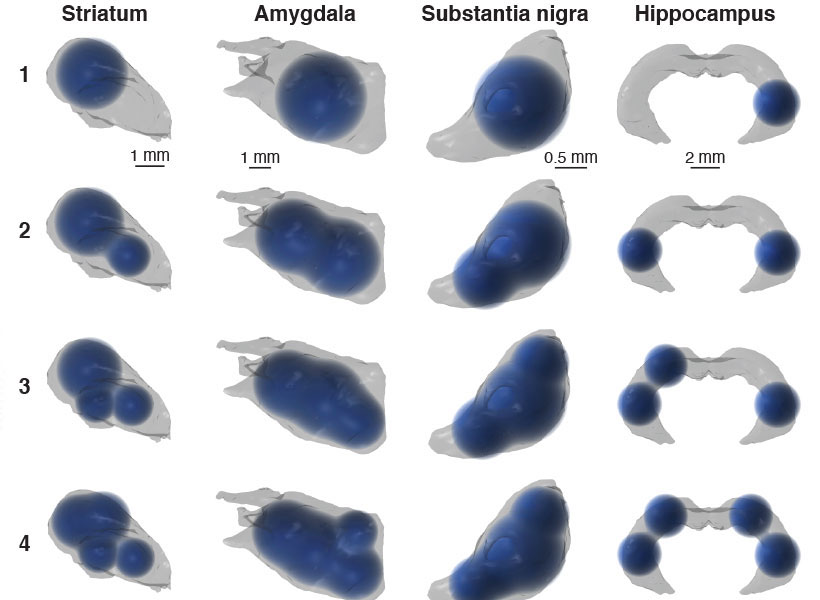

Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from.

Taking advantage of its pernicious spread, neuroscientists use a modified version of the rabies virus to introduce a fluorescent protein to infected cells and visualize their connections (above). As a graduate student in Edward Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Wickersham figured out how to limit the virus’s passage through the nervous system, allowing it to access cells that are directly connected to the neuron it initially infects, but go no further. Rabies virus travels across synapses in the opposite direction of neuronal signals, so researchers can deliver it to a single cell or set of cells, then see exactly where those cells’ inputs are coming from.

Labs around the world use Wickersham’s modified rabies virus to trace neuronal anatomy in the brains of mice. While his team tinkers to make the virus even more powerful, his collaborators have deployed it to map a variety of essential connections, offering clues into how the brain controls movement, detects odors, and retrieves memories.

With the newest tracing tool from the Wickersham lab, moving from anatomical studies to experiments that reveal circuit function is seamless, because the lab has further modified their virus so that it cannot kill cells. Researchers can label connected cells, then proceed to monitor their signals or manipulate their activity in the same animals.

Researchers usually conduct these experiments in genetically modified mice to control the subset of cells that activate the tracing system. It’s the same approach used to restrict most virally-delivered tools to specific neurons, which is crucial, Feng says. When introducing a fluorescent protein for imaging, for example, “we don’t want the gene we deliver to be activated everywhere, otherwise the whole brain will be lighting up,” he says.

Selective targets

In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret.

In Feng’s lab, research scientist Martin Wienisch is working to make it easier to control this aspect of delivery. Rather than relying on the genetic makeup of an entire animal to determine where a virally-transported gene is switched on, instructions can be programmed directly into the virus, borrowing regulatory sequences that cells already know how to interpret.

Wienisch is scouring the genomes of individual neurons to identify short segments of regulatory DNA called enhancers. He’s focused on those that selectively activate gene expression in just one of hundreds of different neuron types, particularly in animal models that are not very amenable to genetic engineering. “In the real brain, many elements interact to drive cell specific expression. But amazingly sometimes a single enhancer is all we need to get the same effect,” he says.

Researchers are already using enhancers to confine viral tools to select groups of cells, but Wienisch, who is collaborating with Fenna Krienen in Steve McCarroll’s lab at Harvard University, aims to create a comprehensive library. The enhancers they identify will be paired with a variety of genetically-encoded tools and packaged into adeno-associated viruses (AAV), the most widely used vectors in neuroscience. The Feng lab plans to use these tools to better understand the striatum, a part of the primate brain involved in motivation and behavioral choices. “Ideally, we would have a set of AAVs with enhancers that would give us selective access to all the different cell types in the striatum,” Wienisch says.

Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.

Enhancers will also be useful for delivering potential gene therapies to patients, Wienisch says. For many years, the Feng lab has been studying how a missing copy of a gene called Shank3 impairs neurons’ ability to communicate, leading to autism and intellectual disability. Now, they are investigating whether they can overcome these deficits by delivering a functional copy of Shank3 to the brain cells that need it. Widespread activation of the therapeutic gene might do more harm than good, but incorporating the right enhancer could ensure it is delivered to the appropriate cells at the right dose, Wienisch says.

Like most gene therapies in development, the therapeutic Shank3, which is currently being tested in animal models, is packaged into an AAV. AAVs safely and efficiently infect human cells, and by selecting the right type, therapies can be directed to specific cells. But AAVs are small viruses, capable of carrying only small genes. Xian Gao, a postdoctoral researcher in the Feng lab, has pared Shank3 down to its most essential components, creating a “minigene” that can be packaged inside the virus, but some things are difficult to fit inside an AAV. Therapies that aim to correct mutations using the CRISPR gene editing system, for example, often exceed the carrying capacity of an AAV.

Expanding options

“There’s been a lot of really phenomenal advances in our gene editing toolkit,” says Victoria Madigan, a postdoctoral researcher in McGovern Investigator Feng Zhang’s lab, where researchers are developing enzymes to more precisely modify DNA. “One of the main limitations of employing these enzymes clinically has been their delivery.”

To open up new options for gene therapy, Zhang and Madigan are working with a group of viruses called densoviruses. Densoviruses and AAVs belong to the same family, but about 50 percent more DNA can be packed inside the outer shell of some densoviruses.

They are an esoteric group of viruses, Madigan says, infecting only insects and crustaceans and perhaps best known for certain members’ ability to devastate shrimp farms. While densoviruses haven’t received a lot of attention from scientists, their similarities to AAV have given the team clues about how to alter their outer capsids to enable them to enter human cells, and even direct them to particular cell types. The fact that they don’t naturally infect people also makes densoviruses promising candidates for clinical use, Madigan says, because patients’ immune systems are unlikely to be primed to reject them. AAV infections, in contrast, are so common that patients are often excluded from clinical trials for AAV-based therapies due to the presence of neutralizing antibodies against the vector.

Ultimately, densoviruses could enable major advances in gene therapy, making it possible to safely deliver sophisticated gene editing systems to patients’ cells, Madigan says — and that’s good reason for scientists to continue exploring the vast diversity in the viral world. “There’s something to be said for looking into viruses that are understudied as new tools,” she says. “There’s a lot of interesting stuff out there — a lot of diversity and thousands of years of evolution.”