Nearly 150 years ago, scientists began to imagine how information might flow through the brain based on the shapes of neurons they had seen under the microscopes of the time. With today’s imaging technologies, scientists can zoom in much further, seeing the tiny synapses through which neurons communicate with one another and even the molecules the cells use to relay their messages. These inside views can spark new ideas about how healthy brains work and reveal important changes that contribute to disease.

This sharper view of biology is not just about the advances that have made microscopes more powerful than ever before. Using methodology developed in the lab of McGovern investigator Edward Boyden, researchers around the world are imaging samples that have been swollen to as much as 20 times their original size so their finest features can be seen more clearly.

“It’s a very different way to do microscopy,” says Boyden, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a member of the Yang Tan Collective at MIT. “In contrast to the last 300 years of bioimaging, where you use a lens to magnify an image of light from an object, we physically magnify objects themselves.” Once a tissue is expanded, Boyden says, researchers can see more even with widely available, conventional microscopy hardware.

Boyden’s team introduced this approach, which they named expansion microscopy (ExM), in 2015. Since then, they have been refining the method and adding to its capabilities, while researchers at MIT and beyond deploy it to learn about life on the smallest of scales.

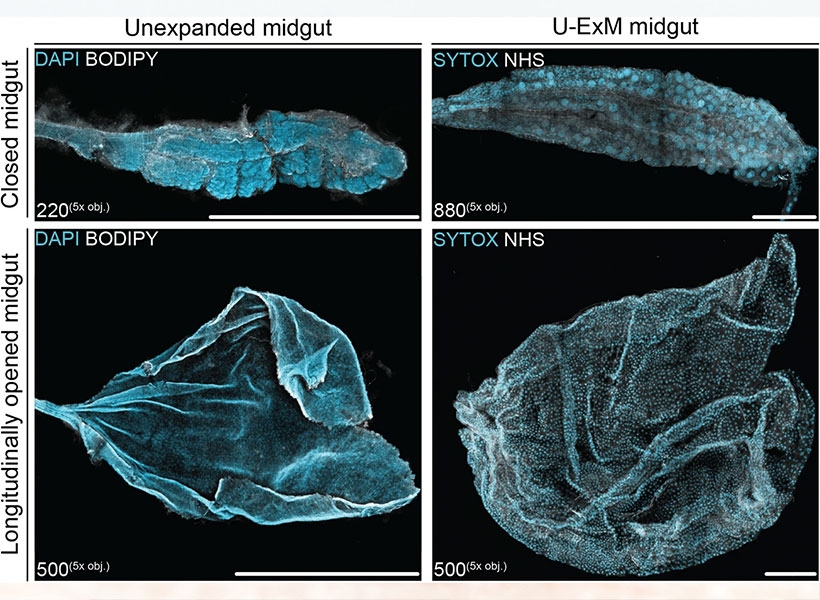

“It’s spreading very rapidly throughout biology and medicine,” Boyden says. “It’s being applied to kidney disease, the fruit fly brain, plant seeds, the microbiome, Alzheimer’s disease, viruses, and more.”

Origins of ExM

To develop expansion microscopy, Boyden and his team turned to hydrogels: a material with remarkable water-absorbing properties that had already been put to practical use: it’s layered inside disposable diapers to keep babies dry. Boyden’s lab hypothesized that hydrogels could retain their structure while they absorbed hundreds of times their original weight in water, expanding the space between their chemical components as they swell.

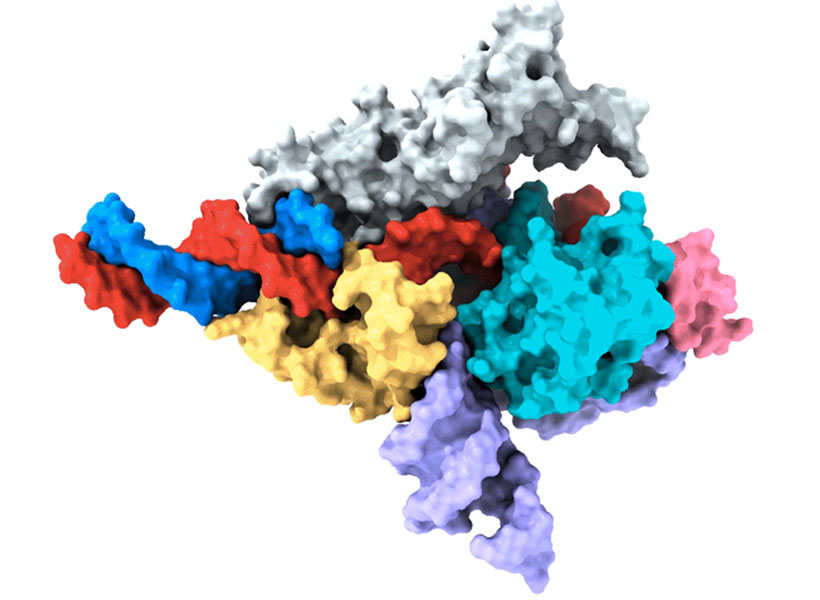

After some experimentation, Boyden’s team settled on four key steps to enlarging tissue samples for better imaging. First, the tissue must be infused with a hydrogel. Components of the tissue, biomolecules, are anchored to the gel’s web-like matrix, linking them directly to the molecules that make up the gel. Then the tissue is chemically softened and water is added. As the hydrogel absorbs the water, it swells and the tissue expands, growing evenly so the relative positions of its components are preserved.

Boyden and graduate students Fei Chen and Paul Tillberg’s first report on expansion microscopy was published in the journal Science in 2015. In it, the team demonstrated that by spreading apart molecules that had been crowded inside cells, features that would have blurred together under a standard light microscope became separate and distinct. Light microscopes can discriminate between objects that are separated by about 300 nanometers—a limit imposed by the laws of physics. With expansion microscopy, Boyden’s group reported an effective resolution of about 70 nanometers, for a four-fold expansion.

Boyden says this is a level of clarity that biologists need. “Biology is fundamentally, in the end, a nanoscale science,” he says. “Biomolecules are nanoscale, and the interactions between biomolecules are over nanoscale distances. Many of the most important problems in biology and medicine involve nanoscale questions.” Several kinds of sophisticated microscopes, each with their own advantages and disadvantages, can bring this kind of detail to light. But those methods are costly and require specialized skills, making them inaccessible for most researchers. “Expansion microscopy democratizes nanoimaging,” Boyden says. “Now anybody can go look at the building blocks of life and how they relate to each other.”

Empowering scientists

Since Boyden’s team introduced expansion microscopy in 2015, research groups around the world have published hundreds of papers reporting on discoveries they have made using expansion microscopy. For neuroscientists, the technique has lit up the intricacies of elaborate neural circuits, exposed how particular proteins organize themselves at and across synapses to facilitate communication between neurons, and uncovered changes associated with aging and disease.

It has been equally empowering for studies beyond the brain. Sabrina Absalon uses expansion microscopy every week in her lab at Indiana University School of Medicine to study the malaria parasite, a single-celled organism packed with specialized structures that enable it to infect and live inside its hosts. The parasite is so small, most of those structures can’t be seen with ordinary light microscopy. “So as a cell biologist, I’m losing the biggest tool to infer protein function, organelle architecture, morphology, linked to function, and all those things–which is my eye,” she says. With expansion, she can not only see the organelles inside a malaria parasite, she can watch them assemble and follow what happens to them when the parasite divides. Understanding those processes, she says, could help drug developers find new ways to interfere with the parasite’s life cycle.

Absalon adds that the accessibility of expansion microscopy is particularly important in the field of parasitology, where a lot of research is happening in parts of the world where resources are limited. Workshops and training programs in Africa, South America, and Asia are ensuring the technology reaches scientists whose communities are directly impacted by malaria and other parasites. “Now they can get super-resolution imaging without very fancy equipment,” Absalon says.

Always Improving

Since 2015, Boyden’s interdisciplinary lab group has found a variety of creative ways to improve expansion microscopy and use it in new ways. Their standard technique today enables better labeling, bigger expansion factors, and higher resolution imaging. Cellular features less than 20 nanometers from one another can now be separated enough to appear distinct under a light microscope.

They’ve also adapted their protocols to work with a range of important sample types, from entire roundworms (popular among neuroscientists, developmental biologists, and other researchers) to clinical samples. In the latter regard, they’ve shown that expansion can help reveal subtle signs of disease, which could enable earlier or less costly diagnoses.

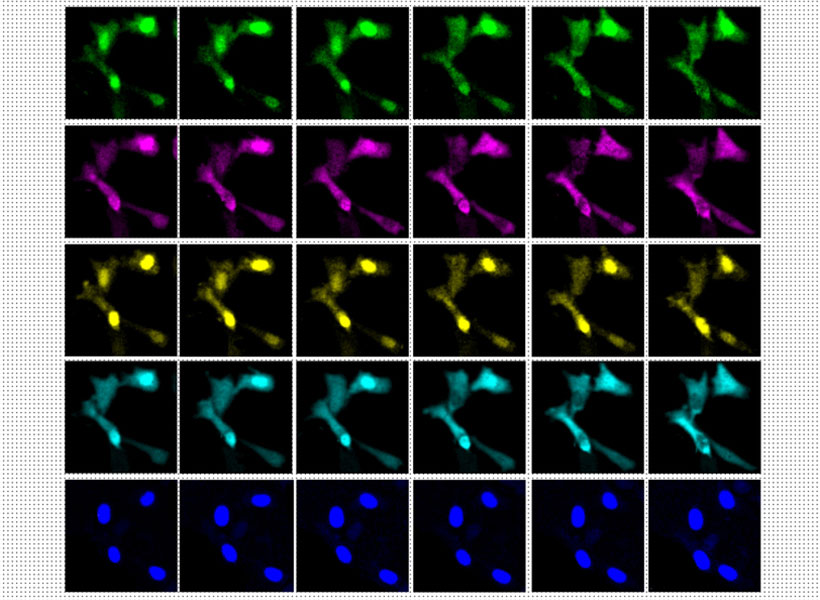

Originally, the group optimized its protocol for visualizing proteins inside cells, by labeling proteins of interest and anchoring them to the hydrogel prior to expansion. With a new way of processing samples, users can now restain their expanded samples with new labels for multiple rounds of imaging, so they can pinpoint the positions of dozens of different proteins in the same tissue. That means researchers can visualize how molecules are organized with respect to one another and how they might interact, or survey large sets of proteins to see, for example, what changes with disease.

But better views of proteins were just the beginning for expansion microscopy. “We want to see everything,” Boyden says. “We’d love to see every biomolecule there is, with precision down to atomic scale.” They’re not there yet—but with new probes and modified procedures, it’s now possible to see not just proteins, but also RNA and lipids in expanded tissue samples.

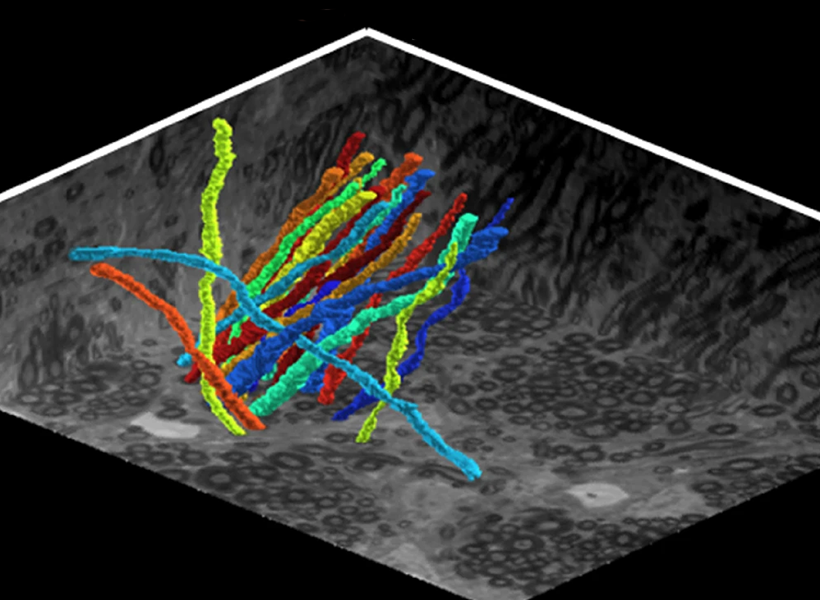

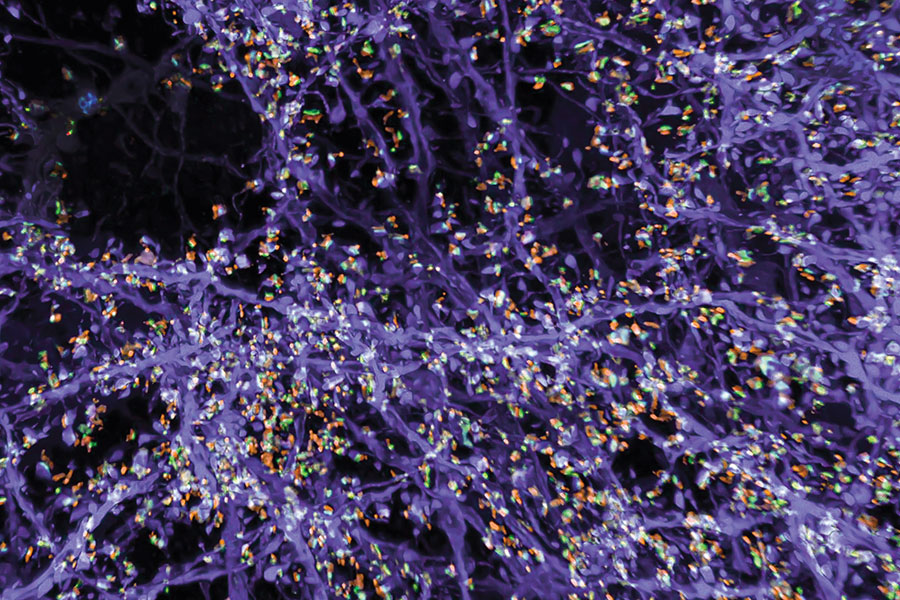

Labeling lipids, including those that form the membranes surrounding cells, means researchers can now see clear outlines of cells in expanded tissues. With the enhanced resolution afforded by expansion, even the slender projections of neurons can be traced through an image. Typically, researchers have relied on electron microscopy, which generates exquisitely detailed pictures but requires expensive equipment, to map the brain’s circuitry. “Now you can get images that look a lot like electron microscopy images, but on regular old light microscopes—the kind that everybody has access to,” Boyden says.

Boyden says expansion can be powerful in combination with other cutting-edge tools. When expanded samples are used with an ultra-fast imaging method developed by Eric Betzig, an HHMI investigator at the University of California, Berkeley, called lattice light-sheet microscopy, the entire brain of a fruit fly can be imaged at high resolution in just a few days. (See HHMI video below).

And when RNA molecules are anchored within a hydrogel network and then sequenced in place, scientists can see exactly where inside cells the instructions for building specific proteins are positioned, which Boyden’s team demonstrated in a collaboration with Harvard University geneticist George Church and then-MIT-professor Aviv Regev. “Expansion basically upgrades many other technologies’ resolutions,” Boyden says. “You’re doing mass-spec imaging, X-ray imaging, or Raman imaging? Expansion just improved your instrument.”

Expanding Possibilities

Ten years past the first demonstration of expansion microscopy’s power, Boyden and his team are committed to continuing to make expansion microscopy more powerful. “We want to optimize it for different kinds of problems, and making technologies faster, better, and cheaper is always important,” he says. But the future of expansion microscopy will be propelled by innovators outside the Boyden lab, too. “Expansion is not only easy to do, it’s easy to modify—so lots of other people are improving expansion in collaboration with us, or even on their own,” Boyden says.

Boyden points to a group led by Silvio Rizzoli at the University Medical Center Göttingen in Germany that, collaborating with Boyden, has adapted the expansion protocol to discern the physical shapes of proteins. At the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, researchers led by Jae-Byum Chang, a former postdoctoral researcher in Boyden’s group, have worked out how to expand entire bodies of mouse embryos and young zebrafish, collaborating with Boyden to set the stage for examining developmental processes and long-distance neural connections with a new level of detail. And mapping connections within the brain’s dense neural circuits could become easier with light-microscopy based connectomics, an approach developed by Johann Danzl and colleagues at the Institute of Science and Technology in Austria that takes advantage of both the high resolution and molecular information that expansion microscopy can reveal.

“The beauty of expansion is that it lets you see a biological system down to its smallest building blocks,” Boyden says.

His team is intent on pushing the method to its physical limits, and anticipates new opportunities for discovery as they do. “If you can map the brain or any biological system at the level of individual molecules, you might be able to see how they all work together as a network—how life really operates,” he says.