In the summer of 2006, before their teenage years began, Mahdi Ramadan and Alexi Choueiri were spirited from their homes amid political unrest in Lebanon. Evacuated on short notice by the U.S. Marines, they were among 2,000 refugees transported to the U.S. on the aircraft carrier USS Nashville.

The two never met in their homeland, nor on the transatlantic journey, and after arriving in the U.S. they went their separate ways. Ramadan and his family moved to Seattle, Washington. Choueiri’s family settled in Chandler, Arizona, where they already had some extended family.

Yet their paths converged 11 years later as graduate students in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS). One day last fall, on a walk across campus, Ramadan and Choueiri slowly unraveled their connection. With increasing excitement, they narrowed it down by year, by month, and eventually, by boat, to discover just how closely their lives had once come to one another.

Lebanon, the only Middle Eastern country without a desert, enjoys a lush, Mediterranean climate. Amid this natural beauty, though, the country struggles under the weight of deep political and cultural divides that sometimes erupt into conflict.

Despite different Lebanese cultural backgrounds — Ramadan’s family is Muslim and Choueiri’s Christian — they have had remarkably similar experiences as refugees from Lebanon. Both credit those experiences with motivating their interest in neuroscience. Questions about human behavior — How do people form beliefs about the world? Can those beliefs really change? — led them to graduate work at MIT.

In pursuit of knowledge

When they first immigrated to the U.S., school symbolized survival for Ramadan and Choueiri. Not only was education a mode of improving their lives and supporting their families, it was a search for objectivity in their recently upended worlds.

As the family’s primary English speaker, Ramadan became a bulwark for his family in their new country, especially in medical matters; his little sister, Ghida, has cerebral palsy. Though his family has limited financial resources, he emphasizes that both he and his sister have been constantly supported by their parents in pursuit of their educations.

In fact, Ramadan feels motivated by Ghida’s determination to complete her degree in occupational therapy: “That to me is really inspirational, her resilience in the face of her disability and in the face of assumptions that people make about capability. She’s really sassy, she’s really witty, she’s really funny, she’s really intelligent, and she doesn’t see her disability as a disability. She actually thinks it’s an advantage — it actually motivated her to pursue [her education] even more.”

Ramadan hopes his own educational journey, from a low-income evacuee to a neuroscience PhD, can show others like him that success is possible.

Choueiri also relied on academics to adapt to his new world in Arizona. Even in Lebanon, he remembers taking solace from a chaotic world in his education, and once in the U.S., he dove headfirst into his studies.

Choueiri’s hometown in Arizona sometimes felt homogenous, so coming to MIT has been a staggering — and welcome — experience. “The diversity here is phenomenal: meeting people from different cultures, upbringings, countries,” he says. “I love making friends from all over and learning their stories. Being a neuroscientist, I like to know how they were brought up and how their ideas were formed. … It’s like Disneyland for me. I feel like I’m coming to Disneyland every day and high-fiving Mickey Mouse.”

At home at MIT

Ramadan and Choueiri revel in the freedom of thought they have found in their academic home here. They say they feel taken seriously as students and, more importantly, as thinkers. The BCS department values interdisciplinary thought, and cultivates extracurricular student activities like philosophy discussion groups, the development of neuroscience podcasts, and independent, student-led lectures on myriad neuroscience-adjacent topics.

Both students were drawn to neuroscience not only by their experiences as Lebanese-Americans, but by trying to make sense of what happened to them at a young age.

Ramadan became interested in neuroplasticity through self-observation. “You know that feeling of childhood you have where everything is magical and you’re not really aware of things around you? I feel like when I immigrated to the U.S., that feeling went away and I had to become extra-aware of everything because I had to adapt so quickly. So, something that intrigued me about neuroscience is how the brain is able to adapt so quickly and how different experiences can shape and rewire your brain.”

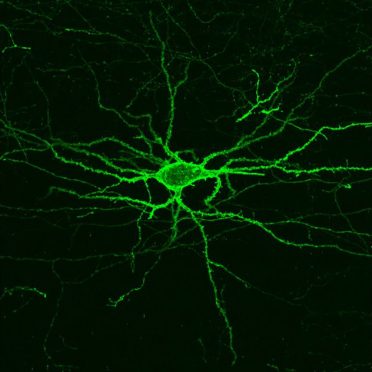

Now in his second year, Ramadan plans to pursue his interest in neuroplasticity in Professor Mehrdad Jazayeri’s lab at the McGovern Institute by investigating how learning changes the brain’s underlying neural circuits; understanding the physical mechanism of plasticity has application to both disease states and artificial intelligence.

Choueiri, a third-year student in the program, is a member of Professor Ed Boyden’s lab at the McGovern Institute. While his interest in neuroscience was similarly driven by his experience as an evacuee, his approach is outward-looking, focused on making sense of people’s choices. Ultimately, the brain controls human ability to perceive, learn, and choose through physiological changes; Choueiri wants to understand not just the human brain, but also the human condition — and to use that understanding to alleviate pain and suffering.

“Growing up in Lebanon, with different religions and war … I became fundamentally interested in human behavior, irrationality, and conflict, and how can we resolve those things … and maybe there’s an objective way to really make sense of where these differences are coming from,” he says. In the Synthetic Neurobiology Group, Choueiri’s research involves developing neurotechnologies to map the molecular interactions of the brain, to reveal the fundamental mechanisms of brain function and repair dysfunction.

Shared identities

As evacuees, Ramadan and Choueiri left their country without notice and without saying goodbye. However, in other ways, their experience was not unlike an immigrant experience. This sometimes makes identifying as a refugee in the current political climate complex, as refugees from Syria and other war-ravaged regions struggle to make a home in the U.S. Still, both believe that sharing their personal experience may help others in difficult positions to see that they do belong in the U.S., and at MIT.

Despite their American identity, Ramadan and Choueiri also share a palpable love for Lebanese culture. They extol the diversity of Lebanese cuisine, which is served mezze-style, making meals an experience full of variety, grilled food, and yogurt dishes. The Lebanese diaspora is another source of great pride for them. Though the population of Lebanon is less than 5 million, as many as 14 million live abroad.

It’s all the more remarkable, then, that Ramadan and Choueiri intersected at MIT, some 6,000 miles from their homeland. The bond they have forged since, through their common heritage, experiences, and interests, is deeply meaningful to both of them.

“I was so happy to find another student who has this story because it allows me to reflect back on those experiences and how they changed me,” says Ramadan. “It’s like a mirror image. … Was it a coincidence, or were our lives so similar that they led to this point?”

This story was written by Bridget E. Begg at MIT’s Office of Graduate Education.