Scientists at the McGovern Institute and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have reengineered a compact RNA-guided enzyme they found in bacteria into an efficient, programmable editor of human DNA. The protein they created, called NovaIscB, can be adapted to make precise changes to the genetic code, modulate the activity of specific genes, or carry out other editing tasks. Because its small size simplifies delivery to cells, NovaIscB’s developers say it is a promising candidate for developing gene therapies to treat or prevent disease.

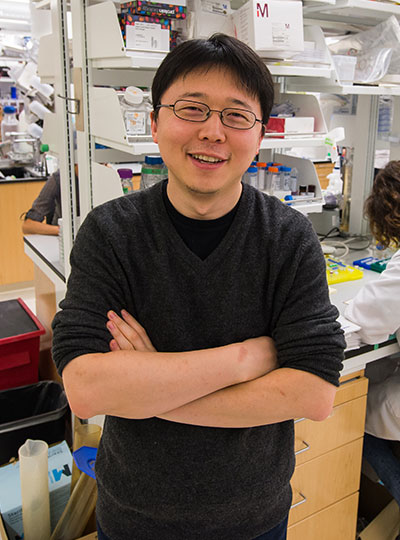

The study was led by McGovern Institute investigator Feng Zhang, who is also the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and a core member of the Broad Institute. Zhang and his team reported their work today in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Compact tools

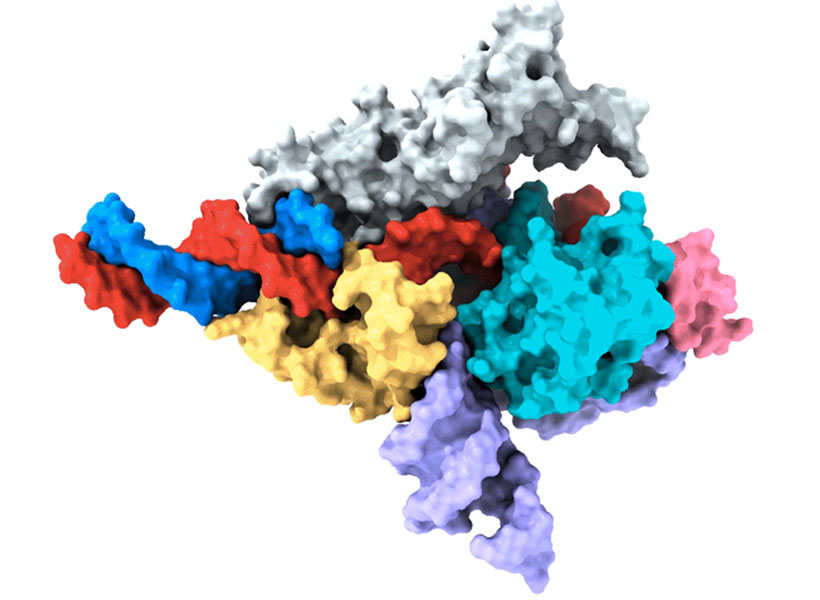

NovaIscB is derived from a bacterial DNA cutter that belongs to a family of proteins called IscBs, which Zhang’s lab discovered in 2021. IscBs are a type of OMEGA system, the evolutionary ancestors to Cas9, which is part of the bacterial CRISPR system that Zhang and others have developed into powerful genome-editing tools. Like Cas9, IscB enzymes cut DNA at sites specified by an RNA guide. By reprogramming that guide, researchers can redirect the enzymes to target sequences of their choosing.

IscBs had caught the team’s attention not only because they share key features of CRISPR’s DNA-cutting Cas9, but also because they are a third of its size. That would be an advantage for potential gene therapies: Compact tools are easier to deliver to cells, and with a small enzyme, researchers would have more flexibility to tinker, potentially adding new functionalities without creating tools that were too bulky for clinical use.

From their initial studies of IscBs, researchers in Zhang’s lab knew that some members of the family could cut DNA targets in human cells. None of the bacterial proteins worked well enough to be deployed therapeutically, however: The team would have to modify an IscB to ensure it could edit targets in human cells efficiently without disturbing the rest of the genome.

To begin that engineering process, Soumya Kannan, a graduate student in Zhang’s lab who is now a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows, and postdoctoral fellow Shiyou Zhu first searched for an IscB that would make good starting point. They tested nearly 400 different IscB enzymes that can be found in bacteria. Ten were capable of editing DNA in human cells.

Even the most active of those would need to be enhanced to make it a useful genome editing tool. The challenge would be increasing the enzyme’s activity, but only at the sequences specified by its RNA guide. If the enzyme became more active, but indiscriminately so, it would cut DNA in unintended places. “The key is to balance the improvement of both activity and specificity at the same time,” explains Zhu.

Zhu notes that bacterial IscBs are directed to their target sequences by relatively short RNA guides, which makes it difficult to restrict the enzyme’s activity to a specific part of the genome. If an IscB could be engineered to accommodate a longer guide, it would be less likely to act on sequences beyond its intended target.

To optimize IscB for human genome editing, the team leveraged information that graduate student Han Altae-Tran, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington, had learned about the diversity of bacterial IscBs and how they evolved. For instance, the researchers noted that IscBs that worked in human cells included a segment they called REC, which was absent in other IscBs. They suspected the enzyme might need that segment to interact with the DNA in human cells. When they took a closer look at the region, structural modeling suggested that by slightly expanding part of the protein, REC might also enable IscBs to recognize longer RNA guides.

Based on these observations, the team experimented with swapping in parts of REC domains from different IscBs and Cas9s, evaluating how each change impacted the protein’s function. Guided by their understanding of how IscBs and Cas9s interact with both DNA and their RNA guides, the researchers made additional changes, aiming to optimize both efficiency and specificity.

In the end, they generated a protein they called NovaIscB, which was over 100 times more active in human cells than the IscB they had started with and that had demonstrated good specificity for its targets.

Kannan and Zhu constructed and screened hundreds of new IscBs before arriving at NovaIscB—and every change they made to the original protein was strategic. Their efforts were guided by their team’s knowledge of IscBs’ natural evolution as well as predictions of how each alteration would impact the protein’s structure, made using an artificial intelligence tool called AlphaFold2. Compared to traditional methods of introducing random changes into a protein and screening for their effects, this rational engineering approach greatly accelerated the team’s ability to identify a protein with the features they were looking for.

The team demonstrated that NovaIscB is a good scaffold for a variety of genome editing tools. “It biochemically functions very similarly to Cas9, and that makes it easy to port over tools that were already optimized with the Cas9 scaffold,” Kannan says. With different modifications, the researchers used NovaIscB to replace specific letters of the DNA code in human cells and to change the activity of targeted genes.

Importantly, the NovaIscB-based tools are compact enough to be easily packaged inside a single adeno-associated virus (AAV)—the vector most commonly used to safely deliver gene therapy to patients. Because they are bulkier, tools developed using Cas9 can require a more complicated delivery strategy.

Demonstrating NovaIscB’s potential for therapeutic use, Zhang’s team created a tool called OMEGAoff that adds chemical markers to DNA to dial down the activity of specific genes. They programmed OMEGAoff to repress a gene involved in cholesterol regulation, then used AAV to deliver the system to the livers of mice, leading to lasting reductions in cholesterol levels in the animals’ blood.

The team expects that NovaIscB can be used to target genome editing tools to most human genes, and look forward to seeing how other labs deploy the new technology. They also hope others will adopt their evolution-guided approach to rational protein engineering. “Nature has such diversity and its systems have different advantages and disadvantages,” Zhu says. “By learning about that natural diversity, we can make the systems we are trying to engineer better and better.”

This study was funded in part by the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics at MIT, Broad Institute Programmable Therapeutics Gift Donors, Pershing Square Foundation, William Ackman, Neri Oxman, the Phillips family, and J. and P. Poitras.