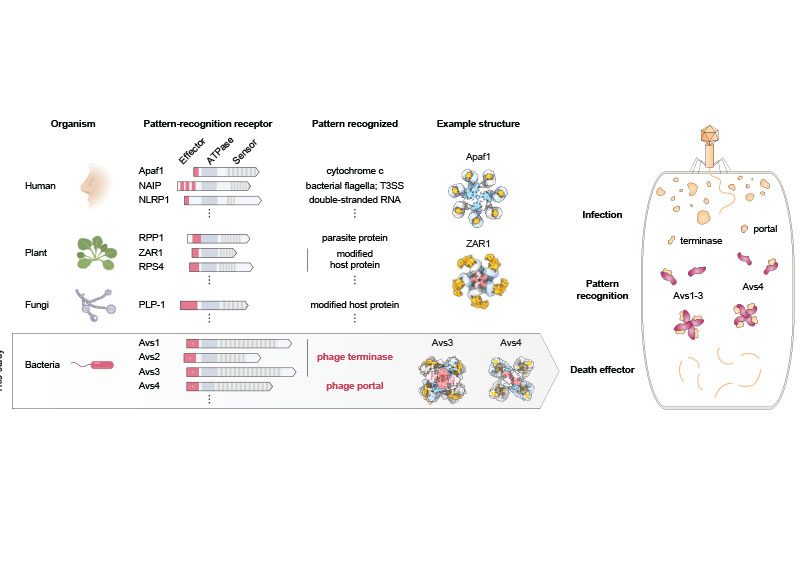

A team led by researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT has discovered and characterized one of these unexplored microbial defense systems. They found that certain proteins in bacteria and archaea (together known as prokaryotes) detect viruses in surprisingly direct ways, recognizing key parts of the viruses and causing the single-celled organisms to commit suicide to quell the infection within a microbial community. The study is the first time this mechanism has been seen in prokaryotes and shows that organisms across all three domains of life — bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (which includes plants and animals) — use pattern recognition of conserved viral proteins to defend against pathogens.

The study appears in Science.

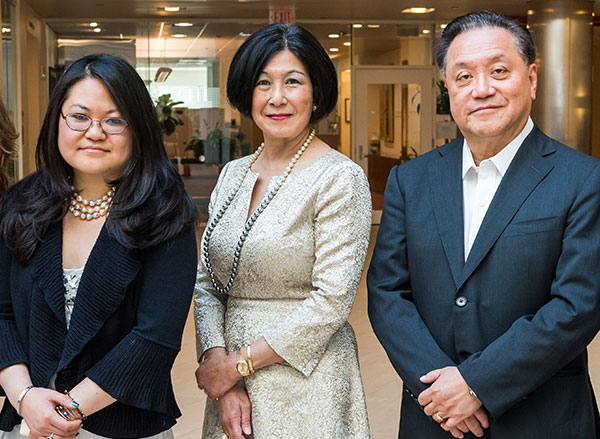

“This work demonstrates a remarkable unity in how pattern recognition occurs across very different organisms,” said senior author Feng Zhang, who is a core institute member at the Broad, the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences and biological engineering at MIT, and an investigator at MIT’s McGovern Institute and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “It’s been very exciting to integrate genetics, bioinformatics, biochemistry, and structural biology approaches in one study to understand this fascinating molecular system.”

Microbial armory

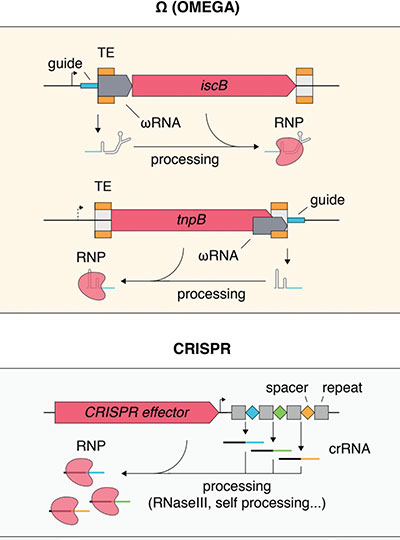

In an earlier study, the researchers scanned data on the DNA sequences of hundreds of thousands of bacteria and archaea, which revealed several thousand genes harboring signatures of microbial defense. In the new study, they homed in on a handful of these genes encoding enzymes that are members of the STAND ATPase family of proteins, which in eukaryotes are involved in the innate immune response.

In humans and plants, the STAND ATPase proteins fight infection by recognizing patterns in a pathogen itself or in the cell’s response to infection. In the new study, the researchers wanted to know if the proteins work the same way in prokaryotes to defend against infection. The team chose a few STAND ATPase genes from the earlier study, delivered them to bacterial cells, and challenged those cells with bacteriophage viruses. The cells underwent a dramatic defensive response and survived.

The scientists next wondered which part of the bacteriophage triggers that response, so they delivered viral genes to the bacteria one at a time. Two viral proteins elicited an immune response: the portal, a part of the virus’s capsid shell, which contains viral DNA; and the terminase, the molecular motor that helps assemble the virus by pushing the viral DNA into the capsid. Each of these viral proteins activated a different STAND ATPase to protect the cell.

The finding was striking and unprecedented. Most known bacterial defense systems work by sensing viral DNA or RNA, or cellular stress due to the infection. These bacterial proteins were instead directly sensing key parts of the virus.

The team next showed that bacterial STAND ATPase proteins could recognize diverse portal and terminase proteins from different phages. “It’s surprising that bacteria have these highly versatile sensors that can recognize all sorts of different phage threats that they might encounter,” said co-first author Linyi Gao, a junior fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows and a former graduate student in the Zhang lab.

Structural analysis

For a detailed look at how the microbial STAND ATPases detect the viral proteins, the researchers used cryo-electron microscopy to examine their molecular structure when bound to the viral proteins. “By analyzing the structure, we were able to precisely answer a lot of the questions about how these things actually work,” said co-first author Max Wilkinson, a postdoctoral researcher in the Zhang lab.

The team saw that the portal or terminase protein from the virus fits within a pocket in the STAND ATPase protein, with each STAND ATPase protein grasping one viral protein. The STAND ATPase proteins then group together in sets of four known as tetramers, which brings together key parts of the bacterial proteins called effector domains. This activates the proteins’ endonuclease function, shredding cellular DNA and killing the cell.

The tetramers bound viral proteins from other bacteriophages just as tightly, demonstrating that the STAND ATPases sense the viral proteins’ three-dimensional shape, rather than their sequence. This helps explain how one STAND ATPase can recognize dozens of different viral proteins. “Regardless of sequence, they all fit like a hand in a glove,” said Wilkinson.

STAND ATPases in humans and plants also work by forming multi-unit complexes that activate specific functions in the cell. “That’s the most exciting part of this work,” said Strecker. “To see this across the domains of life is unprecedented.”

The research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Open Philanthropy, the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation, the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research, the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research, the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience, the Phillips family, J. and P. Poitras, and the BT Charitable Foundation.