Neurons communicate with each other via electrical impulses, which are produced by ion channels that control the flow of ions such as potassium and sodium. In a surprising new finding, MIT neuroscientists have shown that human neurons have a much smaller number of these channels than expected, compared to the neurons of other mammals.

The researchers hypothesize that this reduction in channel density may have helped the human brain evolve to operate more efficiently, allowing it to divert resources to other energy-intensive processes that are required to perform complex cognitive tasks.

“If the brain can save energy by reducing the density of ion channels, it can spend that energy on other neuronal or circuit processes,” says Mark Harnett, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the study.

Harnett and his colleagues analyzed neurons from 10 different mammals, the most extensive electrophysiological study of its kind, and identified a “building plan” that holds true for every species they looked at — except for humans. They found that as the size of neurons increases, the density of channels found in the neurons also increases.

However, human neurons proved to be a striking exception to this rule.

“Previous comparative studies established that the human brain is built like other mammalian brains, so we were surprised to find strong evidence that human neurons are special,” says former MIT graduate student Lou Beaulieu-Laroche.

Beaulieu-Laroche is the lead author of the study, which appears today in Nature.

A building plan

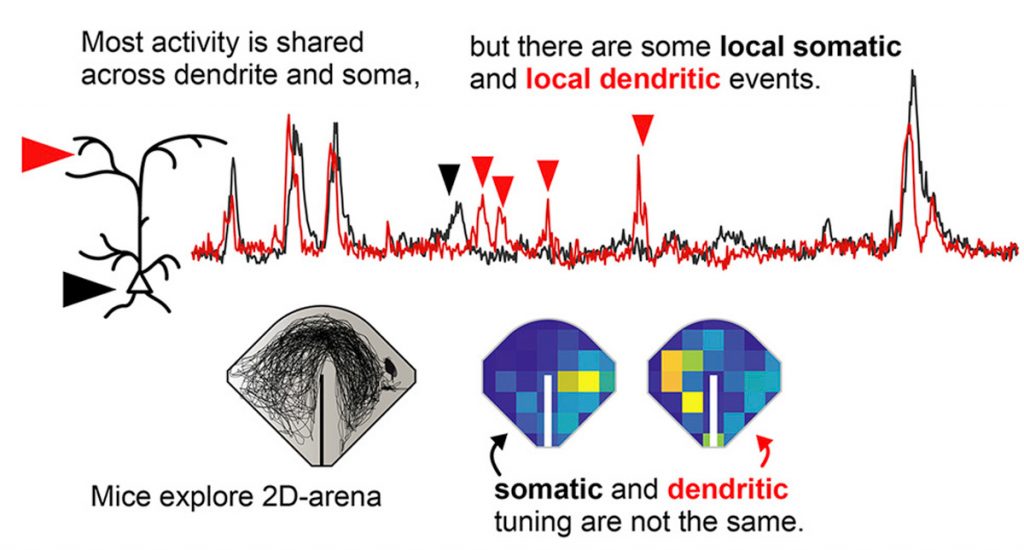

Neurons in the mammalian brain can receive electrical signals from thousands of other cells, and that input determines whether or not they will fire an electrical impulse called an action potential. In 2018, Harnett and Beaulieu-Laroche discovered that human and rat neurons differ in some of their electrical properties, primarily in parts of the neuron called dendrites — tree-like antennas that receive and process input from other cells.

One of the findings from that study was that human neurons had a lower density of ion channels than neurons in the rat brain. The researchers were surprised by this observation, as ion channel density was generally assumed to be constant across species. In their new study, Harnett and Beaulieu-Laroche decided to compare neurons from several different mammalian species to see if they could find any patterns that governed the expression of ion channels. They studied two types of voltage-gated potassium channels and the HCN channel, which conducts both potassium and sodium, in layer 5 pyramidal neurons, a type of excitatory neurons found in the brain’s cortex.

They were able to obtain brain tissue from 10 mammalian species: Etruscan shrews (one of the smallest known mammals), gerbils, mice, rats, Guinea pigs, ferrets, rabbits, marmosets, and macaques, as well as human tissue removed from patients with epilepsy during brain surgery. This variety allowed the researchers to cover a range of cortical thicknesses and neuron sizes across the mammalian kingdom.

The researchers found that in nearly every mammalian species they looked at, the density of ion channels increased as the size of the neurons went up. The one exception to this pattern was in human neurons, which had a much lower density of ion channels than expected.

The increase in channel density across species was surprising, Harnett says, because the more channels there are, the more energy is required to pump ions in and out of the cell. However, it started to make sense once the researchers began thinking about the number of channels in the overall volume of the cortex, he says.

In the tiny brain of the Etruscan shrew, which is packed with very small neurons, there are more neurons in a given volume of tissue than in the same volume of tissue from the rabbit brain, which has much larger neurons. But because the rabbit neurons have a higher density of ion channels, the density of channels in a given volume of tissue is the same in both species, or any of the nonhuman species the researchers analyzed.

“This building plan is consistent across nine different mammalian species,” Harnett says. “What it looks like the cortex is trying to do is keep the numbers of ion channels per unit volume the same across all the species. This means that for a given volume of cortex, the energetic cost is the same, at least for ion channels.”

Energy efficiency

The human brain represents a striking deviation from this building plan, however. Instead of increased density of ion channels, the researchers found a dramatic decrease in the expected density of ion channels for a given volume of brain tissue.

The researchers believe this lower density may have evolved as a way to expend less energy on pumping ions, which allows the brain to use that energy for something else, like creating more complicated synaptic connections between neurons or firing action potentials at a higher rate.

“We think that humans have evolved out of this building plan that was previously restricting the size of cortex, and they figured out a way to become more energetically efficient, so you spend less ATP per volume compared to other species,” Harnett says.

He now hopes to study where that extra energy might be going, and whether there are specific gene mutations that help neurons of the human cortex achieve this high efficiency. The researchers are also interested in exploring whether primate species that are more closely related to humans show similar decreases in ion channel density.

The research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, a Friends of the McGovern Institute Fellowship, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellows Program, the Dana Foundation David Mahoney Neuroimaging Grant Program, the National Institutes of Health, the Harvard-MIT Joint Research Grants Program in Basic Neuroscience, and Susan Haar.

Other authors of the paper include Norma Brown, an MIT technical associate; Marissa Hansen, a former post-baccalaureate scholar; Enrique Toloza, a graduate student at MIT and Harvard Medical School; Jitendra Sharma, an MIT research scientist; Ziv Williams, an associate professor of neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School; Matthew Frosch, an associate professor of pathology and health sciences and technology at Harvard Medical School; Garth Rees Cosgrove, director of epilepsy and functional neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Sydney Cash, an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital.