Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, along with their collaborators at the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Ragon Institute, have been working on a CRISPR-based diagnostic for Covid-19 that can produce results in 30 minutes to an hour, with similar accuracy as the standard PCR diagnostics now used.

The new test, known as STOPCovid, is still in the research stage but, in principle, could be made cheaply enough that people could test themselves every day. In a study appearing today in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers showed that on a set of patient samples, their test detected 93 percent of the positive cases as determined by PCR tests for Covid-19.

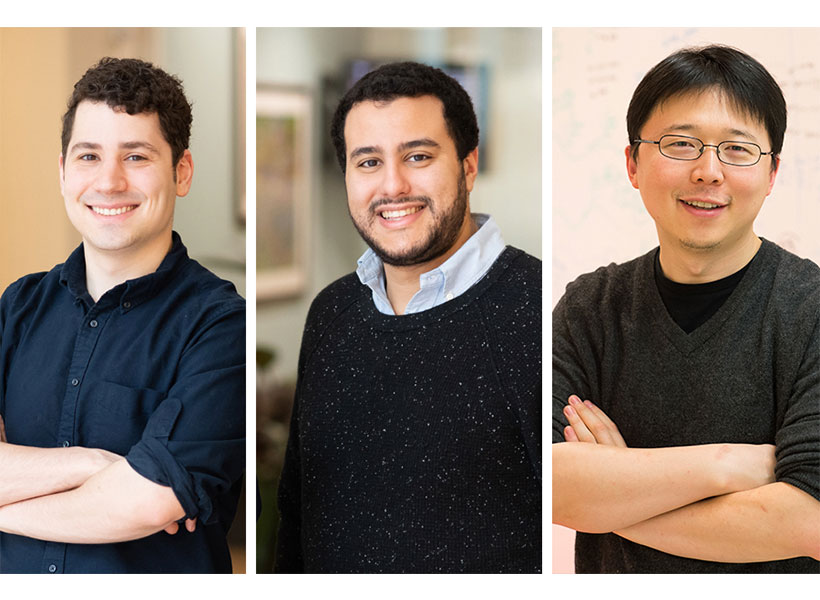

“We need rapid testing to become part of the fabric of this situation so that people can test themselves every day, which will slow down outbreak,” says Omar Abudayyeh, an MIT McGovern Fellow working on the diagnostic.

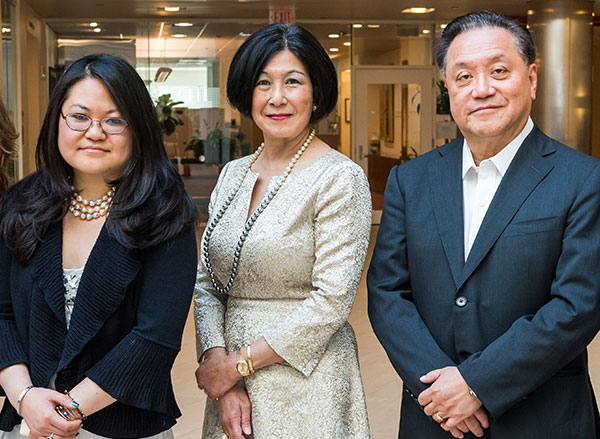

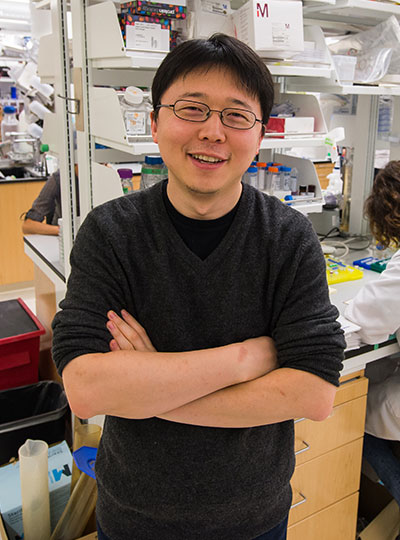

Abudayyah is one of the senior authors of the study, along with Jonathan Gootenberg, a McGovern Fellow, and Feng Zhang, a core member of the Broad Institute, investigator at the MIT McGovern Institute and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the James and Patricia Poitras ’63 Professor of Neuroscience at MIT. The first authors of the paper are MIT biological engineering graduate students Julia Joung and Alim Ladha in the Zhang lab.

A streamlined test

Zhang’s laboratory began collaborating with the Abudayyeh and Gootenberg laboratory to work on the Covid-19 diagnostic soon after the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak began. They focused on making an assay, called STOPCovid, that was simple to carry out and did not require any specialized laboratory equipment. Such a test, they hoped, would be amenable to future use in point-of-care settings, such as doctors’ offices, pharmacies, nursing homes, and schools.

“We developed STOPCovid so that everything could be done in a single step,” Joung says. “A single step means the test can be potentially performed by nonexperts outside of laboratory settings.”

In the new version of STOPCovid reported today, the researchers incorporated a process to concentrate the viral genetic material in a patient sample by adding magnetic beads that attract RNA, eliminating the need for expensive purification kits that are time-intensive and can be in short supply due to high demand. This concentration step boosted the test’s sensitivity so that it now approaches that of PCR.

“Once we got the viral genomes onto the beads, we found that that could get us to very high levels of sensitivity,” Gootenberg says.

Working with collaborators Keith Jerome at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Alex Greninger at the University of Washington, the researchers tested STOPCovid on 402 patient samples — 202 positive and 200 negative — and found that the new test detected 93 percent of the positive cases as determined by the standard CDC PCR test.

“Seeing STOPCovid working on actual patient samples was really gratifying,” Ladha says.

They also showed, working with Ann Woolley and Deb Hung at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, that the STOPCovid test works on samples taken using the less invasive anterior nares swab. They are now testing it with saliva samples, which could make at-home tests even easier to perform. The researchers are continuing to develop the test with the hope of delivering it to end users to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The goal is to make this test easy to use and sensitive, so that we can tell whether or not someone is carrying the virus as early as possible,” Zhang says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Evergrande Covid-19 Response Fund, the Mathers Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Open Philanthropy Project, J. and P. Poitras, and R. Metcalfe.