The Office of the Vice Chancellor and the Registrar’s Office have announced this year’s Margaret MacVicar Faculty Fellows: materials science and engineering Professor Polina Anikeeva, literature Professor Mary Fuller, chemical engineering Professor William Tisdale, and electrical engineering and computer science Professor Jacob White.

Role models both in and out of the classroom, the new fellows have tirelessly sought to improve themselves, their students, and the Institute writ large. They have reimagined curricula, crossed disciplines, and pushed the boundaries of what education can be. They join a matchless academy of scholars committed to exceptional instruction and innovation.

Vice Chancellor Ian Waitz will honor the fellows at this year’s MacVicar Day symposium, “Learning through Experience: Education for a Fulfilling and Engaged Life.” In a series of lightning talks, student and faculty speakers will examine how MIT — through its many opportunities for experiential learning — supports students’ aspirations and encourages them to become engaged citizens and thoughtful leaders.

The event will be held on March 13 from 2:30-4 p.m. in Room 6-120. A reception will follow in Room 2-290. All in the MIT community are welcome to attend.

For nearly three decades, the MacVicar Faculty Fellows Program has been recognizing exemplary undergraduate teaching and advising around the Institute. The program was named after Margaret MacVicar, the first dean for undergraduate education and founder of the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP). Nominations are made by departments and include letters of support from colleagues, students, and alumni. Fellows are appointed to 10-year terms in which they receive $10,000 per year of discretionary funds.

Polina Anikeeva

“I’m speechless,” Polina Anikeeva, associate professor of materials science and engineering and brain and cognitive sciences, says of becoming a MacVicar Fellow. “In my opinion, this is the greatest honor one could have at MIT.”

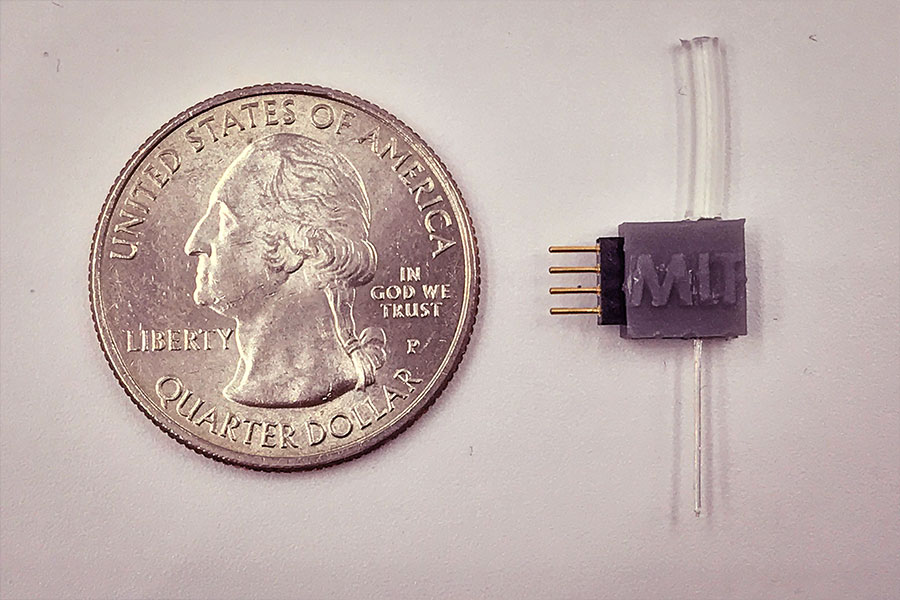

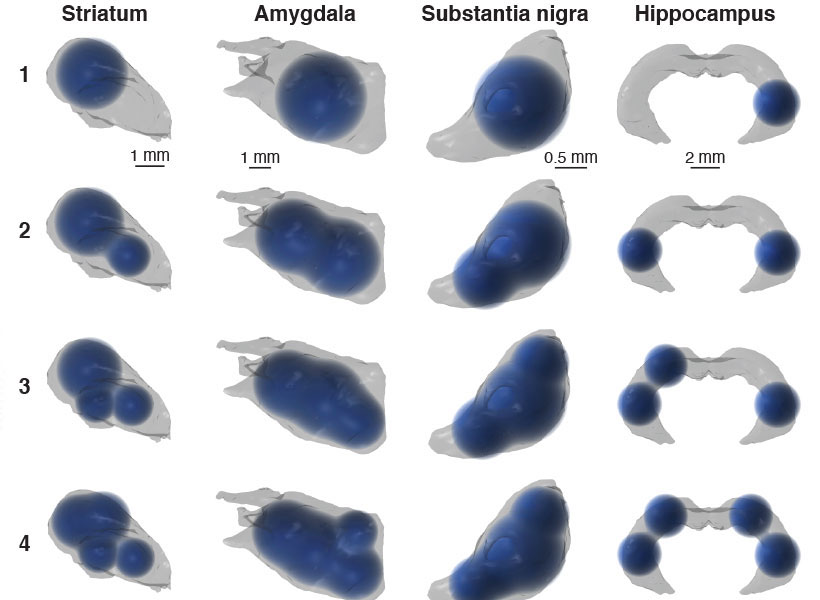

Anikeeva received her PhD from MIT in 2009 and became a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering two years later. She attended St. Petersburg State Polytechnic University for her undergraduate education. Through her research — which combines materials science, electronics, and neurobiology — she works to better understand and treat brain disorders.

Anikeeva’s colleague Christopher Schuh says, “Her ability and willingness to work with students however and whenever they need help, her engaging classroom persona, and her creative solutions to real-time challenges all culminate in one of MIT’s most talented and beloved undergraduate professors.”

As an instructor, advisor, and marathon runner, Anikeeva has learned the importance of finding balance. Her colleague Lionel Kimerling reflects on this delicate equilibrium: “As a teacher, Professor Anikeeva is among the elite who instruct, inspire, and nurture at the same time. It is a difficult task to demand rigor with a gentle mentoring hand.”

Students call her classes “incredibly hard” but fun and exciting at the same time. She is “the consummate scientist, splitting her time evenly between honing her craft, sharing knowledge with students and colleagues, and mentoring aspiring researchers,” wrote one.

Her passion for her work and her devotion to her students are evident in the nomination letters. One student recounted their first conversation: “We spoke for 15 minutes, and after talking to her about her research and materials science, I had never been so viscerally excited about anything.” This same student described the guidance and support Anikeeva provided her throughout her time at MIT.

After working with Anikeeva to apply what she learned in the classroom to a real-world problem, this student recalled, “I honestly felt like an engineer and a scientist for the first time ever. I have never felt so fulfilled and capable. And I realize that’s what I want for the rest of my life — to feel the highs and lows of discovery.”

Anikeeva champions her students in faculty and committee meetings as well. She is a “reliable advocate for student issues,” says Caroline Ross, associate department head and professor in DMSE. “Professor Anikeeva is always engaged with students, committed to student well-being, and passionate about education.”

“Undergraduate teaching has always been a crucial part of my MIT career and life,” Anikeeva reflects. “I derive my enthusiasm and energy from the incredibly talented MIT students — every year they surprise me with their ability to rise to ever-expanding intellectual challenges. Watching them grow as scientists, engineers, and — most importantly — people is like nothing else.”

Mary Fuller

Experimentation is synonymous with education at MIT and it is a crucial part of literature Professor Mary Fuller’s classes. As her colleague Arthur Bahr notes, “Mary’s habit of starting with a discrete practical challenge can yield insights into much broader questions.”

Fuller attended Dartmouth College as an undergraduate, then received both her MA and PhD in English and American literature from The Johns Hopkins University. She began teaching at MIT in 1989. From 2013 to 2019, Fuller was head of the Literature Section. Her successor in the role, Shankar Raman, says that her nominators “found [themselves] repeatedly surprised by the different ways Mary has pushed the limits of her teaching here, going beyond her own comfort zones to experiment with new texts and techniques.”

“Probably the most significant thing I’ve learned in 30 years of teaching here is how to ask more and better questions,” says Fuller. As part of a series of discussions on ethics and computing, she has explored the possibilities of artificial intelligence from a literary perspective. She is also developing a tool for the edX platform called PoetryViz, which would allow MIT students and students around the world to practice close reading through poetry annotation in an entirely new way.

“We all innovate in our teaching. Every year. But, some of us innovate more than others,” Krishna Rajagopal, dean for digital learning, observes. “In addition to being an outstanding innovator, Mary is one of those colleagues who weaves the fabric of undergraduate education across the Institute.”

Lessons learned in Fuller’s class also underline the importance of a well-rounded education. As one alumna reflected, “Mary’s teaching carried a compassion and ethic which enabled non-humanities students to appreciate literature as a diverse, valuable, and rewarding resource for personal and social reflection.”

Professor Fuller, another student remarked, has created “an environment where learning is not merely the digestion of rote knowledge, but instead the broad-based exploration of ideas and the works connected to them.”

“Her imagination is capacious, her knowledge is deep, and students trust her — so that they follow her eagerly into new and exploratory territory,” says Professor of Literature Stephen Tapscott.

Fuller praises her students’ willingness to take that journey with her, saying, “None of my classes are required, and none are technical, so I feel that students have already shown a kind of intellectual generosity by putting themselves in the room to do the work.”

For students, the hard work is worth it. Mary Fuller, one nominator declared, is exactly “the type of deeply impactful professor that I attended MIT hoping to learn from.”

William Tisdale

William Tisdale is the ARCO Career Development Professor of chemical engineering and, according to his colleagues, a “true star” in the department.

A member of the faculty since 2012, he received his undergraduate degree from the University of Delaware and his PhD from the University of Minnesota. After a year as a postdoc at MIT, Tisdale became an assistant professor. His research interests include nanotechnology and energy transport.

Tisdale’s colleague Kristala Prather calls him a “curriculum fixer.” During an internal review of Course 10 subjects, the department discovered that 10.213 (Chemical and Biological Engineering) was the least popular subject in the major and needed to be revised. After carefully evaluating the coursework, and despite having never taught 10.213 himself, Tisdale envisioned a novel way of teaching it. With his suggestions, the class went from being “despised” to loved, with subject evaluations improving by 70 percent from one spring to the next. “I knew Will could make a difference, but I had no idea he could make that big of a difference in just one year,” remarks Prather.

One student nominator even went so far as to call 10.213, as taught by Tisdale, “one of my best experiences at MIT.”

Always patient, kind, and adaptable, Tisdale’s willingness to tackle difficult problems is reflected in his teaching. “While the class would occasionally start to mutiny when faced with a particularly confusing section, Prof. Tisdale would take our groans on with excitement,” wrote one student. “His attitude made us feel like we could all get through the class together.” Regardless of how they performed on a test, wrote another, Tisdale “clearly sent the message that we all always have so much more to learn, but that first and foremost he respected you as a person.”

“I don’t think I could teach the way I teach at many other universities,” Tisdale says. “MIT students show up on the first day of class with an innate desire to understand the world around them; all I have to do is pull back the curtain!”

“Professor Tisdale remains the best teacher, mentor, and role model that I have encountered,” one student remarked. “He has truly changed the course of my life.”

“I am extremely thankful to be at a university that values undergraduate education so highly,” Tisdale says. “Those of us who devote ourselves to undergraduate teaching and mentoring do so out of a strong sense of responsibility to the students as well as a genuine love of learning. There are few things more validating than being rewarded for doing something that already brings you joy.”

Jacob White

Jacob White is the Cecil H. Green Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) and chair of the Committee on Curricula. After completing his undergraduate degree at MIT, he received a master’s degree and doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley. He has been a member of the Course 6 faculty since 1987.

Colleagues and students alike observed White’s dedication not just to teaching, but to improving teaching throughout the Institute. As Luca Daniel and Asu Ozdaglar of the EECS department noted in their nomination letter, “Jacob completely understands that the most efficient way to make his passion and ideas for undergraduate education have a real lasting impact is to ‘teach it to the teachers!’”

One student wrote that White “has spent significant time and effort educating the lab assistants” of 6.302 (Feedback System Design). As one of these teaching assistants confirmed, White’s “enthusiastic spirit” inspired them to spend hours discussing how to best teach the subject. “Many people might think this is not how they want to spend their Thursday nights,” the student wrote. “I can speak for myself and the other TAs when I say that it was an incredibly fun and educational experience.”

His work to improve instruction has even expanded to other departments. A colleague describes White’s efforts to revamp 8.02 (Physics II) as “Herculean.” Working with a group of students and postdocs to develop experiments for this subject, “he seemed to be everywhere at once … while simultaneously teaching his own class.” Iterations took place over a year and a half, after which White trained the subject’s TAs as well. Hundreds of students are benefitting from these improved experiments.

White is, according to Daniel and Ozdaglar, “a colleague who sincerely, genuinely, and enormously cares about our undergraduate students and their education, not just in our EECS department, but also in our entire MIT home.”

When he’s not fine-tuning pedagogy or conducting teacher training, he is personally supporting his students. A visiting student described White’s attention: “He would regularly meet with us in groups of two to make sure we were learning. In a class of about 80 students in a huge lecture hall, it really felt like he cared for each of us.”

And his zeal has rubbed off: “He made me feel like being excited about the material was the most important thing,” one student wrote.

The significance of such a spark is not lost on White.

“As an MIT freshman in the late 1970s, I joined an undergraduate research program being pioneered by Professor Margaret MacVicar,” he says. “It was Professor MacVicar and UROP that put me on the academic’s path of looking for interesting problems with instructive solutions. It is a path I have walked for decades, with extraordinary colleagues and incredible students. So, being selected as a MacVicar Fellow? No honor could mean more to me.”